The Preserved Wreckage of the World

by Abigail Greenbaum

Susan wanted the Polish sausage to spoil. Her stepbrother Harrison, restaurant co-owner and lifetime vegetarian, was coming for dinner after the shift, and she wanted to feed him bad meat.

“They stuff it right there at the deli,” she said to her manager, Estaban. “You know how I feel about local food. Good for the body, good for the soul. Like yoga!”

Susan knew Esteban despised Cleopatra’s Kitchen, and more so, the fact that she owned the place. Half owned it, anyway. It would be another year at least before she could put the money together to buy Harrison out.

“Very good,” said Esteban, sucking in his puffy cheeks and assessing the brown paper bag, which now dripped sausage grease onto her calendar. “You want to taste from the line?”

Susan walked past him toward the kitchen. As they cruised the pastry station, she heard him mutter at Luis. Jefa, she heard, aguanta.

Susan did not hate being in charge. She was not what her kitchen staff would consider an admirable woman: single, almost forty, no children to speak of. And she loved bossing these men.

Susan glanced back over her shoulder at Esteban and Luis: Yes, yes, yes. Deal with me.

The administrative structure of Cleopatra’s Kitchen didn’t win Susan any peace and love points with Harrison, who was always grilling her about a new health insurance plan, and did she really have to check those social security numbers so closely? She’d offered to cook at home for him that night because she didn’t want him stopping by the kitchen. He had a tendency to wander on the lines, showing off his backpacker Spanish, and then sit her down in the office and repeat the sob stories in an urgent, serious tone. Was she aware that Julio’s rent had gone up? That his wife had been sent back to Honduras? It’s not a commune, she wanted to yell at her brother. It’s a fucking kitchen. Somebody’s got to dump the grease.

All around Susan, knives whispered against stations. She sloshed her finger through Pedro’s saffron marinade, then licked and nodded. “More saffron,” she said, and Esteban winced as the pricy spice clouded above the bowl.

But the stock for the lentil tagine tasted like boiled garlic. “I should spit it right out,” she said to Esteban. “Who’s running this place?”

Esteban bowed his head and said nothing. Everyone in the kitchen swallowed their jokes and would not meet his eye. They waited for Susan to call out the next order. There was no telling what she would want, and whenever she wanted, they jumped.

“Get me a coat,” she said. She whirled between the tables, adjusting the cut on the carrots, spraying just a little more pepper over the beef. Line cooks assembled on either side of her, their hands trembling around hotel pans. They presented their work to her one by one, like patient ambassadors.

In the office, once they’d seated the bulk of the wait, Susan called her brother and opened a bottle of wine.

“Good, good,” said Harrison. “What are you making me?”

“Sweet potato and tempeh hash,” she said. The bulbous tempeh would disguise the meat. “The Harrison special.” Her chef coat crumpled on the floor by the desk.

“See you sooner than soon,” he said. “I know something you’ll want to know.”

Her body felt well worked and deserving of rest. The newspaper on her desk explained about Seventeen Year Cicadas, but Susan couldn’t quite do the math. Were there crops that came every ten years, and different, less ominous ones every seven? Or was it ten plus seven and now was the seventeenth year? It sounded like bible math, lean years and fat, skinny cows preceded by plump ones. Susan didn’t think a cicada and a locust the same, but everyone preferred the second word, sucking on the drama of it. Believe it! Plague Insect Returns!

Susan hadn’t ever been good at math, although she felt good at it, back in high school, when Harrison gave her tabs with cow skulls on them to hold under her tongue as they walked the farm road to school. The acid made the numbers stop swimming through her mind, as if she stood at the edge of a stone pool looking down to where integers buzzed patiently in trim, final equations, unmoved by the turtles or moccasin snakes. What they told you in health class was true: once experienced, a trip stayed with you, no two ways about it. Susan pictured little brown cow skulls lurking in her synapses, dormant, but ready at any moment to shake their curved horns in her mind. She’d tripped through so much of her fifteenth year. It still surprised her she’d been able to deliver the baby at all.

Before leaving Cleopatra’s Kitchen, Susan staked out some space by the ovens and began working through the asanas of a sun salute. She could feel the floor under her stomach, flecked with peppercorns. She raised her hips up toward the ceiling and straightened her arms, not worried about the vegetable peels that hung from her tee shirt like pieces of moss.

“Surya Namaskar,” she answered to Esteban, as she brought her hands back down into a point of prayer against her ribcage. He shook his head and moved back toward the cooler.

“Speak English,” he shouted, over his shoulder. “This is America.” She decided to leave the bottle of wine half full on her desk. She often scattered the kitchen with this kind of temptation. Despite the Whole Body vibe and farm fresh menu at Cleopatra’s Kitchen, restaurants were more Dog-Eat-Dog than anything else, and trust must be tested every day. Every shift.

She was halfway through the second repetition when Esteban returned. He frowned for a minute to see her sprawled on the floor, and then his face lapsed back to its mask of disinterest. “Don’t forget your sausage,” he said, holding the brown bag in her direction, as she peeled her breasts away from the floor and bent her spine backwards. “I put it away in the fridge.”

Harrison moved in when Susan was fourteen, and what she felt for him in those wild times she now recognized as some half-formed parody of love. But after their baby was born, and adopted, she’d run off to the West Coast, bussing it for three days, trying to leave Illinois and its dark forests behind her.

In California, she lived in the basement of a shack on the beach, close to Mexico. There were men who lived upstairs, Heath and Tyler and Jesse. They smelled like salt and did nothing to repair the house. All day, Susan curled on the ripped plaid couch in the basement, and watched the sand blow in through the splintering foundations. She did not learn to surf. She did not sidle to the bonfires, but she could smell the burning, and knew that another day ended. Sometimes a boy–Heath? Jesse?–would come down and lift her onto the floor and unzip her sweatshirt and palm her collarbone. But it wasn’t really him, no matter how hard he pressed her into the floor, no matter how much grit speckled her shoulder blades. It was always Harrison, in one form or another, grinning above her, just as he had in the Forest Preserve. She drank Thunderbird and snorted heroine when the boys offered. When her hair got too salty and tangled to brush, she cut it off, and the shorn pieces lay for weeks in the corner of the basement until someone –Jesse? Heath?—swept them away while she slept. She ate vinegar potato chips for weeks at a time.

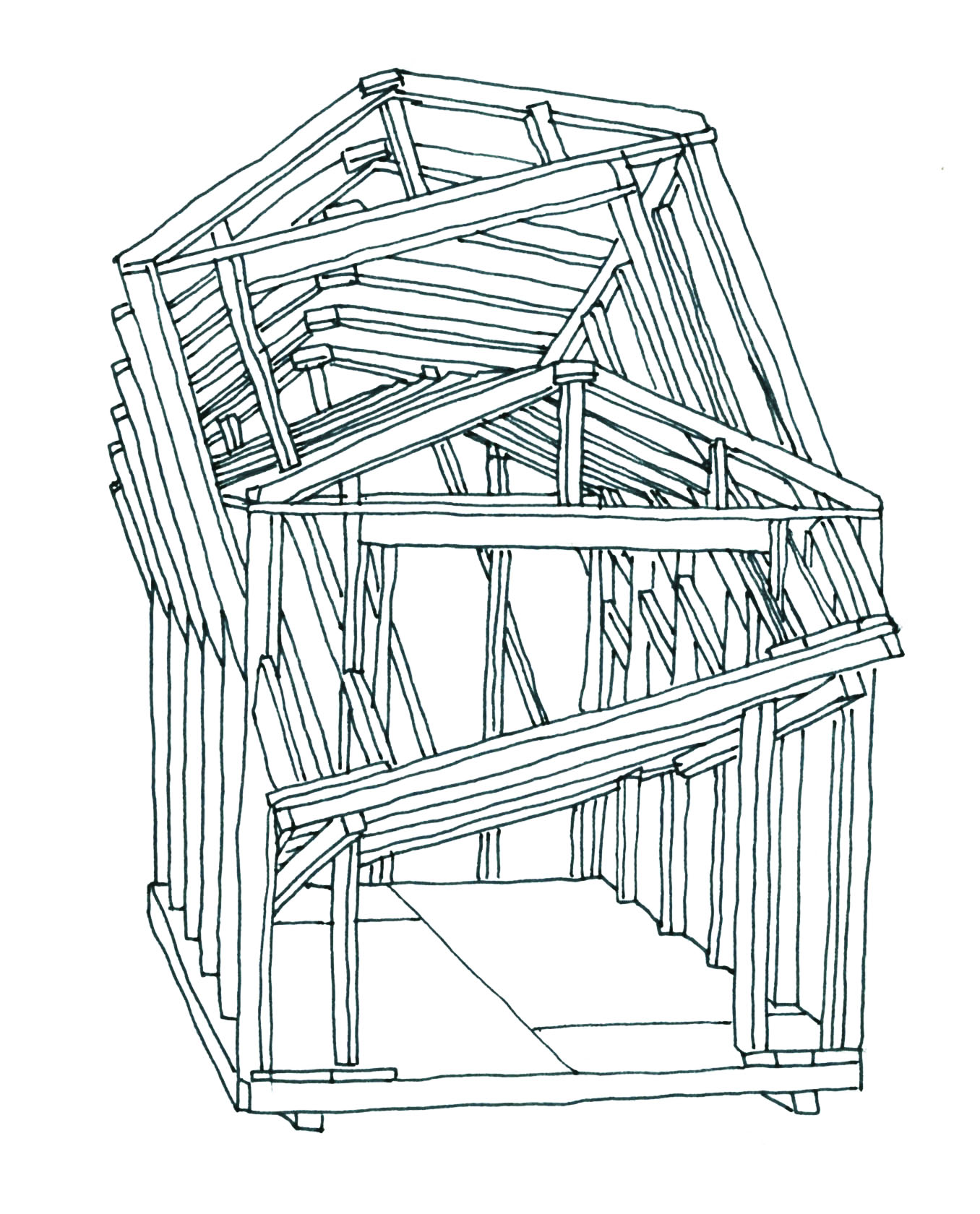

She didn’t know how Harrison tracked her down, or how he had the balls to stage a rescue. But that was who her step-brother had become, she learned later, a salvage man. He worked for himself. He built pedestals for museum exhibits, steady places where the preserved wreckage of the world could stand.

Now he wanted to own her again, in a different way. Not only for the money he was offering–enough to start a small restaurant–but for the fact that he arrived one day at the beach shack and lifted her up in his arms.

As they drove away from the beach, small grasshopper pumpjacks bobbed up and down on otherwise empty lots. Thirsty birds, he had said, patting her shoulder, like you. In the years that followed, first in a clinic in the suburbs, then in the small brick house where she lived alone, and then finally in Cleopatra’s Kitchen, those oil derricks became the center of her meditative practice. I am breathing in, she thought, and the rusted hammerhead teetered toward the ground. I am breathing out. The cross beam tilted up toward the sky, drawing forth precious slick from inside the earth.

While Harrison picked nasturtiums for the salad, Susan smashed the raw links into tiny pieces and folded them into the rest of the hash. Even though Esteban had prevented the meat from spoiling, she could still serve the meal before it cooked through. She filled the steel pan with peppers and fresh thyme, glazed onions and orange potatoes.

They ate on wooden chairs in the garden. Small children shouted in Spanish on the other side of the fence, and baseballs hung in the bluish air, threatening to fall into her unkempt garden.

“I don’t hear any locusts,” said Harrison, swallowing.

“You wouldn’t, not in the city.”

“It’s a fear tactic, really, drummed up to distract us from what they really don’t want us to know.”

“Okay, so let’s say I humor you and your paranoia for a minute. What don’t they want us to know? And who are they, anyway? Let’s put aside the perfectly reasonable explanation that cicadas live in the ground, that’s where they come from, down in the dirt, and in the city there just isn’t any dirt left. But I’ll put that aside, I’m with you, really, I am.”

“You used to believe me.”

“I know. Conspiracy is very reassuring. No matter how sinister, it means that somewhere out there–” She lifted her hand and arced it overhead toward the baseballs that rose and fell like dull, leather moons in the darkness.“–Out there is someone who knows more than I do.”

“Listen. Am I right? No cicadas.”

They sat in silence for a while after that, chewing and sipping and swallowing. They scanned the silhouetted houses on either side, and tires hummed through the alley.

Inside, a telephone rang. “Leave it,” said Harrison. “Stay with me.”

“Eat up, eat up,” she said, as she moved toward the house, “You’re all bones.”

On the phone, Esteban asked direct but tender questions. He didn’t know whether to order more pork.

“Can’t I trust you alone for one night?” Susan stood by the kitchen window and watched Harrison scrape his fork across his plate. Should he order more pork. Should he chain the dumpster, should he lock the door.

“Vault the cash,” she said, slow, measured, as if repeating the alphabet. “Change the water in the renunculus.”

Outside, Harrison leaned back in his lounger and closed his eyes. She’d grown used to her brother’s mystical moves, had even adopted them to a certain extent, although for her the yoga poses felt as urgent and vital as blood sport. She found comfort in Harrison’s trances, the way it was comforting to watch The Wizard of Oz on cable, too grown for its terror. Now she could see the makeup and the wires, the slips between real world and dream. But still, Kansas lurked only a few states a away, and the frames of the movie were colored by her younger self, who thought any slight wind might turn the world upside down.

“Very good, very good,” said Esteban. “You take day off tomorrow?”

“I’ll drop by again in the afternoon.”

“Well,” he said. “All right. We’ll be ready.”

“Of course you will. Take that bottle of Chateau-neuf home with you tonight.” She wondered if he’d already taken it, nestled in his bag, chosen the prep cook to frame.

“Oh thank you, Ms. Susan, thank you so much.”

Other restaurant owners she knew had warned Susan about holding the whole thing too tightly, strangling the vibe. One day, they predicted, customers smile as you pass the table, and the next you hover too close, inspecting the lamb and lentil pharaoh burgers, until they begin to wonder what has gone wrong.

“Tomorrow, Esteban. I’ll see you tomorrow.”

“Yes ma’am.”

Susan clapped her hands until, outside, Harrison stirred in his chair.

“Brother! Didn’t you have a story to tell?”

“Come back out,” he said. “We are free from the plague of the insects.”

“No,” she said, hand still clutching the phone, that plastic comfort where moments before she’d practically been able to hear Esteban cringing and deferring to every sound she made. “Come to the window.”

He deposited his plate on the flagstone and stood below her in the darkness, a low blur.

“Cheers on the grub. Didn’t I always know you were a natural? Who needs meat?”

“Just that our teeth are made for it. But you know I’ll always look out for you. Least I can do.”

Harrison rubbed his stomach, unsnapping a pearl button.

“You did say you had something to tell me, right? Am I making that up? Sometimes I swear I’ve got a sieve for a head. Almost put sausage in that hash. How sick would you be?”

“My fault, I bet. All those drugs I made you.”

“More than drugs, though, wasn’t it.”

“Here’s the thing, Susan. I talked to someone at the agency.”

“So?” She switched off the porch light so he disappeared completely. “I waived my rights. But you know that, don’t you? What do you want?”

“I got the address,” he said. Susan felt reeled back in by his calmness, that face so sure it would get what it wanted that you wanted to play along, be the one to give in. Once again her desire, and her fear of that desire, battled it out.

“It’s time,” she said, “to get going. At the very least I’m going to find us some locusts.”

Susan steered her Jeep between the recycling bins and ragged corn patches that stuck out in the alley.

“Take Lake Shore,” said Harrison, although she hadn’t asked. “Go North.”

“Maybe,” said Susan.

“Doesn’t it blow your mind, knowing he’s out there somewhere?”

“People have babies all the time. It would blow my mind more if he weren’t.” Although she didn’t say so, Susan had been waiting for a chance like this, some proof that she could hold in her hand, squeeze and burst like a peach, the juices trickling over her fingers in a sticky reminder that what happened had happened.

“Careful.” He reached over and steadied the wheel. A man crossed the road in front of them, his shopping cart teetering with drywall and mattress coil.

“He can stop for me.” Susan slapped Harrison’s hand and yanked her vehicle in front of the oncoming cars and onto the Avenue. “I weigh more.” The man cursed them with a wrist wrapped in gauze.

It didn’t surprise Susan that Harrison had talked the confidential info from the agency. He had always been a talker. He’d coached her for the adoption agents, sitting Indian style on her bed. You tell them you don’t remember the man. You tell them you were too young and too scared to press charges. If this makes you sad, just go with it, bawl. The best lies, he’d taught her, were husks around something true.

The day the caseworker arrived a stray sheep flailed next door in the Nixon pool. Susan sat in the living room, looking over the lady’s thick shoulder pads, out the window, out to where Harrison came to the rescue. I didn’t see the man, she said, and the caseworker scribbled on a legal pad. I didn’t tell anyone until I had to. She reached down and pinched her swollen belly. She wanted kicks. She wanted proof.

While the caseworker talked to Susan about how final it was, how she was giving up all the rights to her child, she watched her brother stride to the pool house and remove the hinge pins from the door.

I get it, she said, when the caseworker pressed her lips together. Why do you think we called you? Bright lipstick smeared the blond woman’s lip line. Susan didn’t bother with lipstick anymore. It seemed beside the point. Later, Mr. Nixon would build a stockade fence to keep out sheep and restless children, but on the day Susan waived her maternal rights, his pool glittered in plain view. It wasn’t more than three feet deep, not where Harrison was standing, but still Susan gasped as her stepbrother lowered himself into the water. Are you all right? the caseworker said, and Susan snorted. Now they lifted the door on their shoulders like a coffin and marched out of the pool. They laid it on the grass. Susan sat in silence and the caseworker fidgeted with her pen. Only after the sheep righted itself and shook the pool from its wool, only then would Susan waive her rights.

“North side, you said?” Susan rattled her Jeep onto the Expressway and aimed for the glitter of down town.

“Why not go straight to the lake?”

“Highway’s faster. This hour, anyway.”

“It’s messing with our carbon footprint, head south just to go north again.”

They cruised through the industrial corridor around the river, a thicket of warehouses and processing plants and steel forges that separated the outlying neighborhoods from the Loop.

“I say take your carbon footprint, and shove—”

“You’re really starting to talk like a chef.”

On that night, the painted walls of the buildings seemed to taunt Susan in a personal way. The three-story fetus, sponsored by the Polish diocese, waved its fins at her, choose life! On the roof of the Morton Salt warehouse, the young girl with the purple umbrella, yellow smock too short, kicked at puddles the size of Susan’s house. She imagined that she drove a flying car, a wonder machine that could carry her and Harrison through the city, past the Drive, and out over the lake.

“What’s the address, again?”

“Near Hollywood and Clark. You should be in the other lane. This will put you on 55.”

“You look a little pale. Are you feeling alright?”

“What? I feel fine. We’re headed south, though.”

“I swear you look a pale. I don’t know, I’m just not sure if I’m up for this.” Susan wanted to stall until Harrison sickened, until his body rallied to expel the toxins she’d prepared, until she could travel to her child’s home alone.

“This is one of those moments, Susan. Swallow and jump.”

“You have a service code for the museum? Show me that exhibit you’ve been working on.”

“Body Worlds.”

“Right,” said Susan. “The blood and guts people.” She had been reading up on Harrison’s latest contract, a traveling German exhibit slated for September. Body Worlds displayed plastinated bodies, real people, dead but preserved. It was creepy and famous. Advance tickets had already sold out through Christmas.

“You want to see that? You know there’s women who died pregnant in that show.”

“I have no problem with fetuses. Dead, born, whatever.”

“There’s guys in there now.”

“Perfect,” said Susan. “I don’t really want to be alone with you.” She hoped the meat would hit him in front of some superior, leave him sweating and wretching under the high ceilings of the museum. Maybe he’d get fired. Sell her his shares to Cleopatra’s Kitchen for a desperate basement rate. All that mattered was that some time before he collapsed, shivering, drained, he told her the exact address, and she could go on her own.

They stashed the Jeep in the loading dock and Harrison waved his pass at the all night guard. “Stay in the Exhibit Hall,” Harrison said, as they tramped down a vinyl hallway that belonged in a state nursing home, not a state of the art museum, “the rest is alarmed.” Susan pictured a lattice of lasers guarding the cases, how museum alarms always looked in movies. She had no idea if that was real. And then, Harrison pushed open a door stenciled “Exhibit” and they were standing among the bodies.

As promised, the show displayed real bodies, chemically treated to maintain the shape and color of living, laughing human parts. They’d been sorted out so that each figure contained no more than one organ: the cottony wisps of nerves, the red flaps of muscle, the comforting structure of bone.

“Would you do something like this? Donate?”

Susan stared at a man, posed running, stray veins trailing behind him as if in breeze. “I don’t believe it,” she said. “They’re not real.”

“I’ve been trying to decide all week. Which is better, the veins or the nerves?”

“Isn’t blood supposed to be blue?” They moved past a display filled with smokers’ lungs. Susan frowned, inhaled, tried to hold her breath for the longest time. She’d quit cigarettes five years ago, but still, did she harbor small heads of sooty cauliflower inside her ribcage?

“I don’t get the address thing,” she said.

“Is it really so hard to believe that I might be trying to help you out? What can I do to be right with you?”

“Would the agency even have the right address, though? Think about it. I’m thirty-eight. So that’s what, thirty-eight minus fifteen. Twenty-three he would be today. Give or take a month.”

“Extend-O-Lescence,” said Harrison. “Haven’t you heard? Kids don’t grow up anymore.”

“Do you even know he’s home? That the place has a window you can see in?”

Plywood crates marked “Body Worlds: Chicago” were stacked in the corner. Empty pedestals, not yet rooted, clumped together in the middle of the room. It horrified Susan to think that somewhere, in some German warehouse, there might be hundreds more of these crates, more preserved bodies than the world would ever see. What’s worse than school kids pointing and squawking and spitting at your cartilage? Your cartilage carefully prepared for show, then hidden away.

“I don’t know anything, Susan. I’m trying to truck through it, same as you.”

“You look pale. Sure you’re feeling alright?”

“Look at him, he’s feeling alright.” Harrison nodded toward a blistered liver.

“This is cool,” said Susan. “But a bit moralistic. Why does everything need to be a cautionary tale?”

They moved into the alcove devoted to pregnancy. The bodies remained in their crates. Small crates for the little ones.

“Who thinks about this crap,” said Susan. “When they’re dying in childbirth? No way all these bodies are here by consent.”

“It’s consensual for sure. I know for a fact.”

“Here’s something you don’t know for a fact: you’re a carnivore.” Susan turned for the exit, knowing Harrison would follow. She’d seen enough. As she marched back to the service hallway, she passed a horse, skin peeled back, heart the size of a basketball, rearing toward the arched ceiling of the exhibit hall. Probably the man slung over the pedestal would be riding it in the real exhibit, but for now he lay, thrown, below its hooves.

It only took a few minutes to swing back onto Lake Shore Drive from the Museum. Even though abandoned stockyards and emerging art factories separated them from downtown, the Loop loomed fast in front, as if the northern half of the city and the evening’s unanswered questions returned like a boomerang, too quickly.

“I feel fine,” Harrison said. “I’ve been veg for over twenty years. If I swallowed some poor creature, I would know.”

“Believe what you want to believe,” said Susan. “But on this one thing, I am right. You can’t cleanse it out of you. No matter how much lemonade with cayenne pepper you drink.”

His nonchalance disappointed her. But what did she expect? That with one roll through his gut, he’d know what she wanted, divestment from the restaurant, a vanishing act, freedom? She’d never been the one to come with the airtight plan. That was Harrison’s thing, that ability to see your life scroll forward on a certain path, to follow it. She chose the fog. Always had.

“Maybe you’re right,” she said. They were passing Soldier Field, uplit so the renovation looked like an oversize flying saucer pulling an emergency landing in the side of a Coliseum. “Maybe I should see where he lives. Maybe that will clear something.”

“Now you’re talking.” Harrison thumbed down his window. In the harbor, water slapped against the leisure boats. “See? Insect silence. No cicadas here, either.”

Susan pumped the gas at the red light. She wanted to get through downtown, start cruising by the northern beaches. When they moved forward again, she refused to speak. The nets hung limp between their poles. Susan, not long sober, had foolishly attended Singles Volleyball on the North Avenue beach. Carolina, she said, when one corn broker asked her name, Soledad, she’d answered another.

Lake Shore jagged onto Hollywood, and although Susan knew this, she still had to downshift from fifth to third, surprised by the high rises springing up where the Drive should be.

“Easy,” said Harrison, gripping his stomach. “Pedal on the left. You’ll have to get off Hollywood, you know.”

She knew he was right, that you couldn’t cross Ridge to Clark, that the neighborhood where her son had maybe broken windows with baseballs was a maze of crooked one-way streets, a weird abandonment of the city’s insistent grid. She steamed north on Ridge, doubled back with an illegal left turn. Harrison checked the alleys for cops. Susan knew they wouldn’t get pulled over. That would be too simple, an officer of the law peering on their stagnation and their struggle and their guilt. No, they were going to have to face this themselves.

Susan parked and suggested they cut through the alley. Maybe the smell from the Dumpsters might help along his food poisoning, although she wasn’t holding out.

“What are we going to do, ring the bell?”

“Maybe,” said Susan. “I don’t know. I am waiting for a path to reveal itself.”

“This should be the block,” said Harrison, as they moved onto a dark side street. In the shadows Susan saw a mix of three-flat buildings and cottages, long yards heavy under spruce and catalpa trees. It seemed too dark for the city. Although she knew she wouldn’t, she expected to hear cicadas here. In almost all the houses, the shades were drawn. In one second-floor apartment, window clear, Susan saw a young woman looking at herself in a mirror, big hair, bra. She was too young to be the boy’s adoptive mother, and Susan knew she didn’t have a man in there. She stood in the mirror, sunk in some other, more peaceful kind of loneliness. She had nothing to do with Susan or Harrison or their son.

“Something doesn’t add up,” Harrison said, resting his sneaker on a fire hydrant. “The block just stops. Numbers are too high still, but they stop.” A courtyard building elbowed around the street’s end, halting their progress.

“I told you, they wouldn’t provide information like that. It’s confidential. I waived my rights.”

“What do you mean?”

They turned back toward where they’d parked.

“I bet they have a list. Ghost houses, flaws in the system, buildings that don’t exist.”

“You think they set me up.” They were back in the alley now, close to the car.

“This must be where they send all the fools like us.”

“I feel sick.”

“Well,” said Susan, waiting as he leaned against a latticed backstairs. “That’s to be expected.”

“Please,” he said, wincing and sucking his lips over his teeth until he looked like an old man. “Take me home.”

“Not yet.” She pictured them climbing back in the Jeep, continuing north toward the dark suburban shore. “I’m going to find you some locusts.”

“Harrison, roll down your window.” They were lost in the suburbs now, out of the city, no system to how the streets, all named for trees, fed and thwarted and escaped one another.

“Right. The air might do me good.”

“No,” she said. “Listen.”

Susan heard buzzing in the trees, but not loud enough to warrant special attention. When Harrison started talking again, he did not increase his volume, just continued in an indoor voice.

“Is it worth it? I feel wrecked.”

It was worth it, actually, but she didn’t tell Harrison that. She saw the most obvious things. There were her hands on the steering wheel, driving deeper into the dark, nameless town. There was Harrison sticking his head out the window, letting the branches slap and poke around his face. There were cicadas in the trees and in the bushes, in the air and in the ground. She saw their shadows flit through the headlight beams. All over the Chicago area they were doing their business, seventeen years worth of desire before they sunk back into the ground. Whoever he was, she hoped her son was listening.

Four teenagers idled in what must have been their parents’ Lexus. Cigarettes glowed inside the car. One boy leered out the window as Susan passed, screwing his brow into knots and distortions, waving his middle finger above his fist at her.

She squealed into the shoulder fifty feet in front of the boys. Before Harrison could say a word she opened her door and walked toward the Lexus.

The driver gunned the engine but Susan kept walking toward their car, daring them to get into trouble. She placed both her palms on the edge of their hood and stared into the steamed up windshield. One of the boys had written something across the glass. The letters were backward, and Susan couldn’t decipher the name. The boy on the passenger side twisted his head and shoulders out the window.

“What you going to do about it, lady?”

“Viparita Shalabhasana,” she said, throwing his face into confusion. He looked down toward his friends in the car and she shouted the English translation. “Reverse Locust.”

Susan knew that you weren’t supposed to do yoga without taking the proper precautions. A flat surface was the minimum, of course, and also the presence of eyes you could trust. Every studio worth its mats would tell you that, although Susan suspected that in this department, if not in others, concerns about litigation had polluted the ancient teachings.

She wanted to grab that punk by his scruff, to say stop, stop, stop, go home, go home to your mother, but as far as trust went, his eyes would have to do. Even if the math was wrong, Susan felt like any son in the world could be hers.

She bounced her feet once on the bumper, then crawled roof-ward like a spider. She spread her body out to its full length and began to breathe in time. As Susan prepared herself for the posture, the boys in the car sat up out the windows, and their heads appeared to float along the sides of the roof.

She counted her breaths. Fourteen, Fifteen, Sixteen. By now he’s much older than that. Inhale–he knows nothing about you–Exhale–nothing about Harrison, the night he was made–Inhale–no matter what–Exhale–he is through these woods.

Once she had set her shoulders in the correct position she kicked her legs up toward the night sky until they steadied somewhere in front of her head. She knew you were supposed to empty your mind of all its consideration, to breathe all the trouble of yourself out like sand from a pail. But it was far too late for that. Behind her she heard Harrison, puking by the side of the road. The boys did not make a sound. They opened and closed their mouths as pet fish might, bumping against the glassed-in limit of their world. Her spine was curved like an early moon and below her shoulders the roof of the car seemed to crumple like foil.