How to Photograph Your Newborn

by Krys Malcolm Belc

1.) 1987

When you bring the baby home from the hospital, you’re supposed to put it down in a bassinet. But before the baby comes, the bassinet just sits there, waiting. In the corner it looks profoundly empty, unsettling almost, before there is anyone to place inside. The emptiness follows you around the room, while you shuffle around folding tiny baby laundry, stacking swaddling blankets just so, changing again and again which is on top, which will be first. Open and close the new hamper just for baby clothes to make sure it, in fact, opens and closes like it should. Stand looking inside, trying to decide whether to open a package of pacifiers now, whether to open a baby thermometer, wondering if these are silly things to do before there is even a baby.

When the baby comes home, swaddle it. The nurse showed you how. Don’t bother with the stack of blankets beside the changing table; grab the one they gave you at the hospital. It’s scrunched up inside the baby’s car seat. The blue and pink lines. On top of your bedspread lay the blanket out flat, then fold corner to corner. Lay the baby’s head just above the blanket’s edge, marveling at the little crushed ears, pointed on top like elf ears, red like they’ve just been out in the sun, red like when you lie or drink too much. Try to remember how to do it, remember those fast, experienced hands. It was so late at night when she showed you, and the baby was so new, and you were so sore, and so tired. Everything felt slow and confusing. The nurse lay two ibuprofen in a cup by the nightstand and wrapped the baby up tight, roughly, almost, before taking your blood pressure and urging you to get some rest. You picked the wrapped baby up and put it to your breast, feeling a deep pulling inside, where there was a baby just hours ago. Now you are the thing that is empty. And here you are, at home now, next to the impossibly empty bassinet, tugging with hesitation, folding the blanket over your baby, hoping it holds, laying the baby down to sleep. Was there something to hold onto inside? Where is this baby trying to go?

Having a summer baby is lucky because you do not have to dress it in so many layers. Dress the baby in one more layer than you’d wear, the nurse says. Dress the baby same as you, the baby’s pediatrician says. You are bleary and leaking and only half listening each time you’re given advice and are not sure you’ve really heard any of it.

No matter; it is so hot you’d rather walk around in your underwear, so you select an undershirt, three-month size, so large and baggy you can see the baby’s entire diaper sticking through. It is not a cute look. You mistakenly think no one will see a baby, shoved inside an enormous perambulator like this, but each head you pass swivels back to look inside. You

have made something everyone wants to see. As you walk down the sidewalk, listening to the ice cream truck wailing and the open fire hydrant roaring on the corner, you hum a little, because the baby is asleep and you are for once alone with your own thoughts, the sounds of your new unswollen feet shuffling along towards nothing, away from home, from the rocking chair, from the couch where you’ve spent the first few days nursing. A baby cries out from a neighbor’s window; under your tee shirt your breasts leak sweet, hot milk. Your mother warned you about the pain and tingling of letdown, but in the beginning there is so much milk that it just falls out of you, all the time, sliding around all sides of your breasts if you lie flat, falling between you and the baby if you lie together nursing. There is so much; how can the body make so much food and never grow too tired to make more? Your legs push forward. It is like walking on the beach, this walking so soon after having a baby. Hot and hard and deeply satisfying. You slow down and lean against a light pole, catch a breath, snap a picture; it is hard to get a good one when the baby is always either asleep or attached to you.

We now know that the fetus begins to hear in the second trimester, around nineteen weeks. At first, it mostly hears your heart, slow and calm as you rest, and fast as you try to keep jogging, keep moving, even as you get bigger. It’s noisy in there. But in 1987, nobody knew for sure how noisy. You haven’t seen it, this baby; you just know it was a baby you were not ready for, with a boyfriend you were not so sure you were going to marry. And then you did. In 1983, placement of an electrolarynx over the fetal ear showed consistent response—forceful blinks—only after twenty-eight weeks gestation. But you know the baby can hear; you just know. When no one else is around, you talk to it, not sure how loud you’d have to be for it to hear you. Tell the baby it will be your parents’ first grandchild; that it must root for the Mets, how they just won the World Series. Describe the way the vacuum never works quite as well as you want to, how it always releases an unpleasant musty odor into the basement apartment. We’re in Flatbush, you say. But hopefully not for long. We don’t want to raise a baby around here, you say. You want to believe the baby knows your voice, before it’s even here.

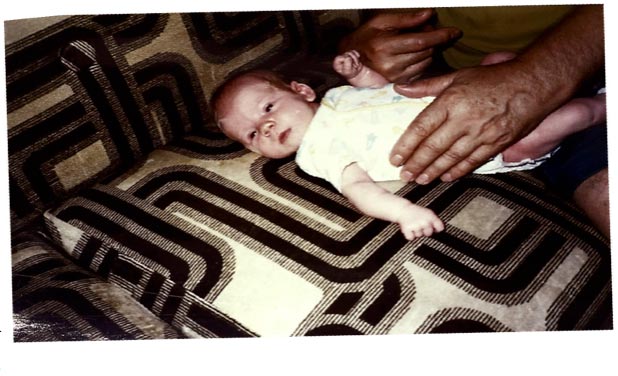

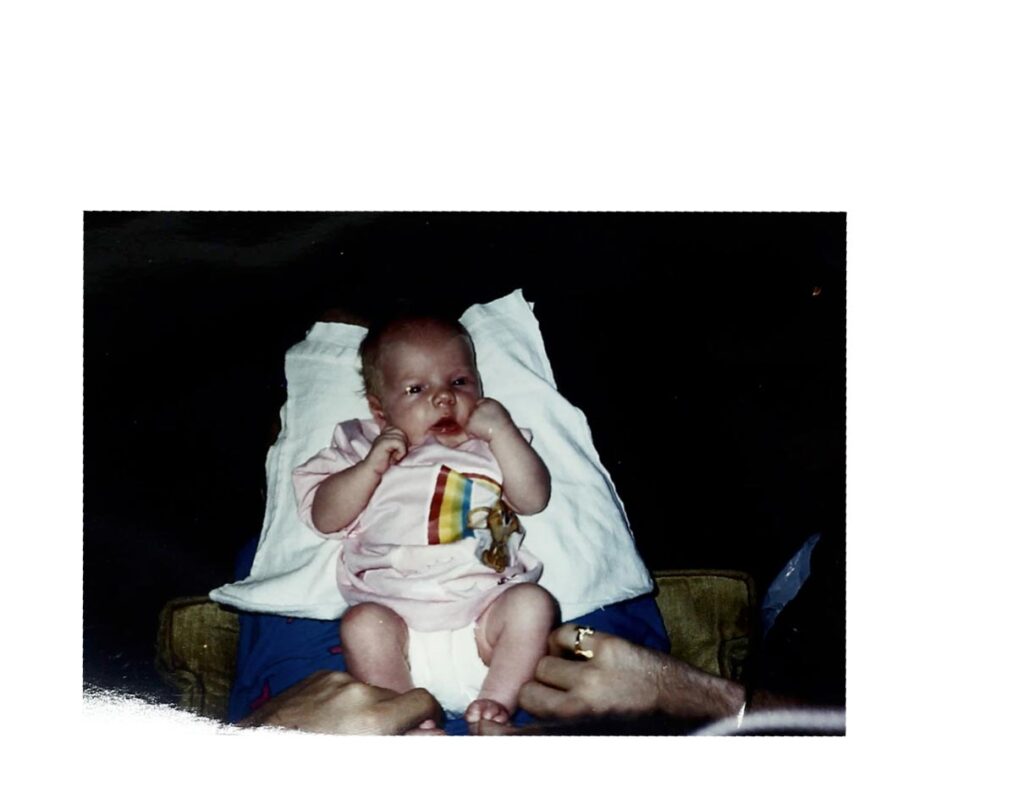

Ask someone to lay hands on the baby, to steady it on the sloped cushion. Whose hands are they—brown, swollen, sun-spotted. Hard, fat hands with nails that need a trim. Hands the size of your baby’s torso. Grab the camera. Your baby knows your voice. Say your baby’s name and lay the baby on a lap. They like that, this other lap. Watch TV together, a family of three. The game. Matlock. Hold the tiny hand next to you; tamp down the jealousy that it is not your lap. Eventually it cannot always be you. Next to you feels so far away; for the better part of a year, you shared one body. You never stood in a long grocery line, sat on hold for an hour, clipped your toenails, woke up in the middle of the night alone. You were never by yourself. Make faces at the baby during commercials. What does the dog say? What does the elephant say? There, do that one again.

Your mother came to this country by herself as a teenager. Maybe, she thought, she’d become a nun. A few years later she was married to the monsignor’s brother and had your brother, Joseph. After that came the miscarriages, the stillbirths. By the time you and your twin brother were born eight years after Joseph it was settled: every baby who lives is a miracle. You were a miracle. The way you and David danced inside, that you kept it up on the outside, too. There aren’t many pictures. You and David in your baptism outfits, one in each parent’s arm, who knows which is which from that far away. The Flatbush church behind them. Your mother short, smiling, smiling at the wonder of it all. Two live babies. How hard it is, how much they cry, it means nothing. You both lived. Your mother never had much to say about before she came to Brooklyn. She tried to make it sound beautiful, where she grew up, but then there was how she left all by herself, the mournful way she said the very word: Ireland. Her soft accent and wet eyes. There is one more picture, the one of you two lying next to one another in a bassinet. You’re screaming. How babies scream sometimes. Eyes closed, mouth open, back arched. David sleeps beside you, his lips loose and limp. You’ve always been you, even then.

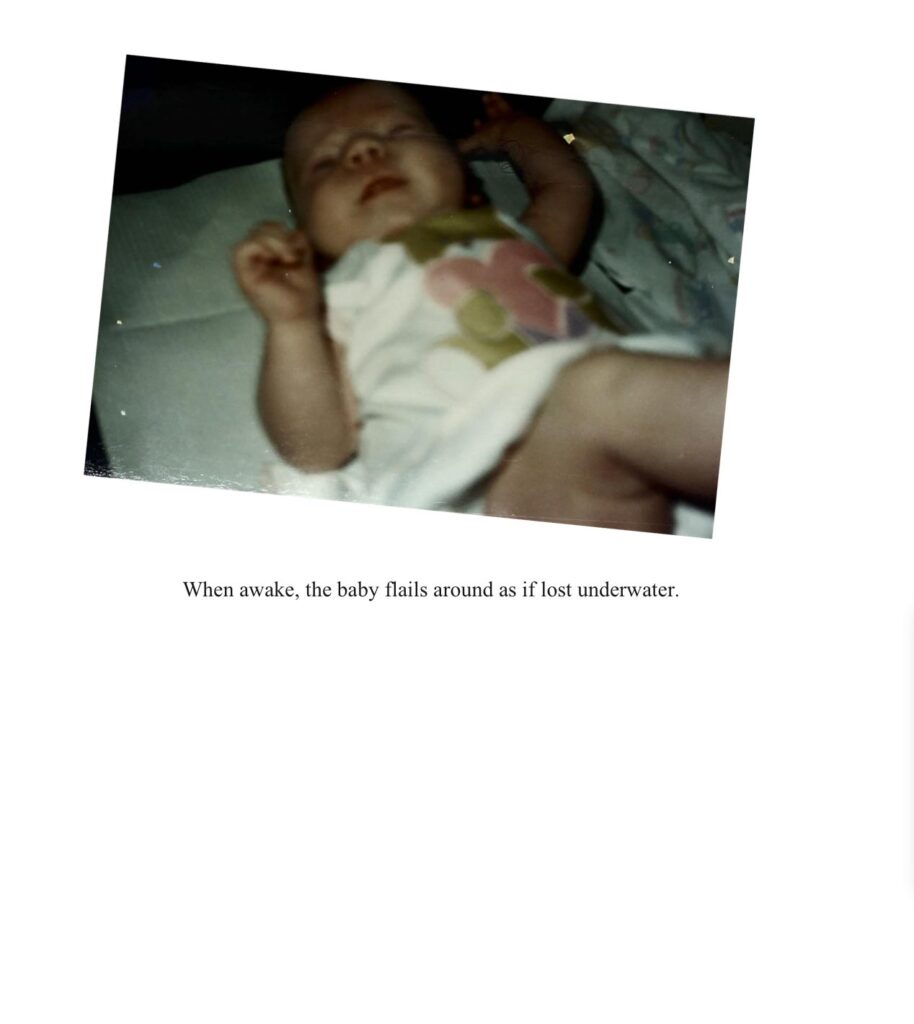

Sometimes the baby can’t be made to smile for the camera. Fresh diaper, fresh milk, that beloved other lap, big hands wiggling tiny toes, Look, look here, what does the elephant say? Say the baby’s name and this is all you get back, this vacant stare. Send me a picture! Your mother says over the phone. She wants to know how things are going. How is the baby eating? How is the baby sleeping? Everything is good, everything is fine, smile for the camera, baby, look over here, right over here.2.) 2013

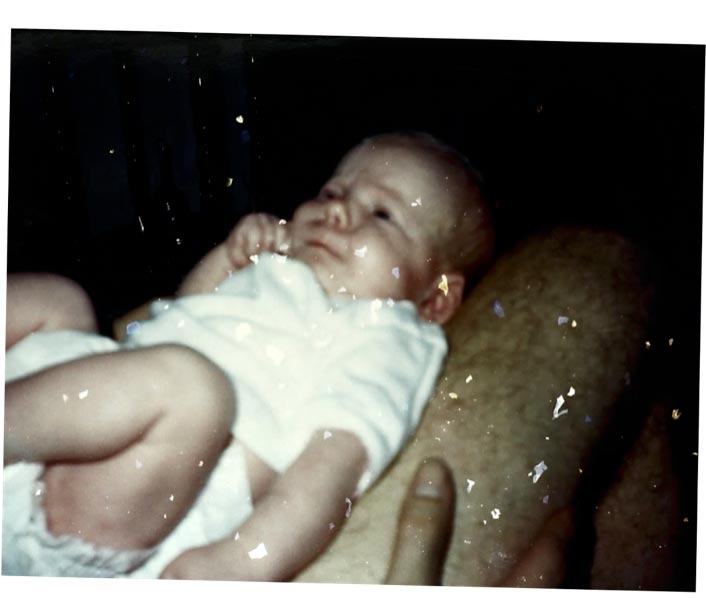

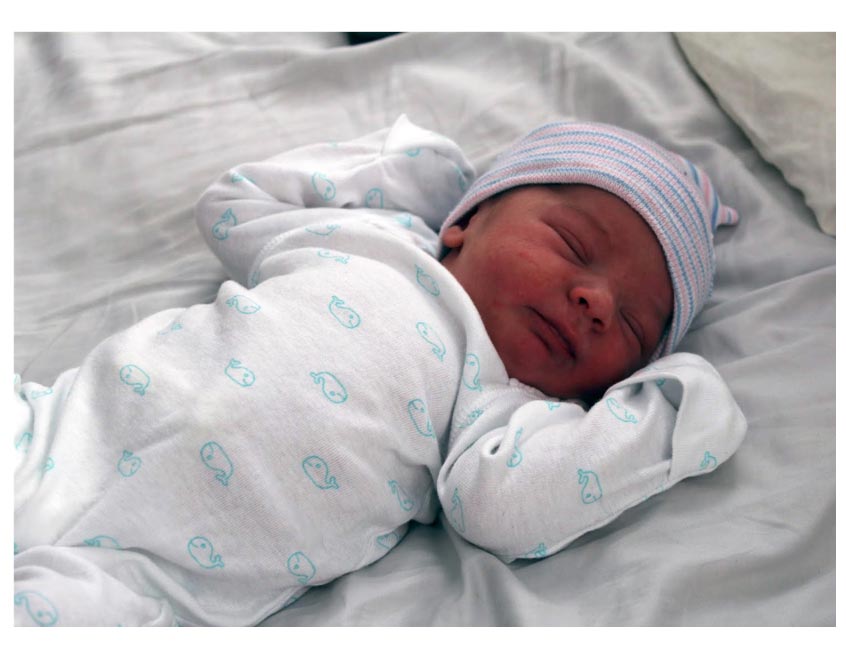

There aren’t any pictures of newborn Samson with both eyes open. We brought him home from the birth center twelve hours after I had him, after eating bagels in bed and having the nurse check him over—his tiny, flat, red ears, skinny legs that stretched wildly when he lay flat on his back. Poppy and sesame seeds spilled over onto wrinkled white sheets. He’s a sleepy little guy, she said. The room smelled of cleaning solution and last night’s Indian takeout; I’d been so happy to give birth at dinner time, to wobble my way to the shower and back to bed again, happy to have the warm bag of food in my hand. Anna let me eat almost all the garlic naan; I swiped it through both our curries while she held the baby. I remember the crisped bits of garlic, the way the bread breathed steam into my face as I tore it apart, cilantro leaves catching in my teeth. I bit down on a whole cardamom pod that was buried in my rice. The perfume exploded in my mouth. Blech, I said, spitting it into a napkin. I was sore, so sore whenever I talked or laughed or moved. I throbbed where the baby had come out of me, this little black-haired baby. He looked exactly like a squashed, red-faced version of my father. I shoveled food into my mouth with a plastic fork, leaning my head over the container of saag paneer. Nothing had never tasted this good. Now all I need is a beer, I’d joked, taking ibuprofen from a little paper cup beside the bed. When Anna had given birth to Sean, I’d laughed at this offering, the tiny orange pills sitting beside all her half-drunk bottles of Gatorade and water, these two ibuprofen after hours of roaring pain.

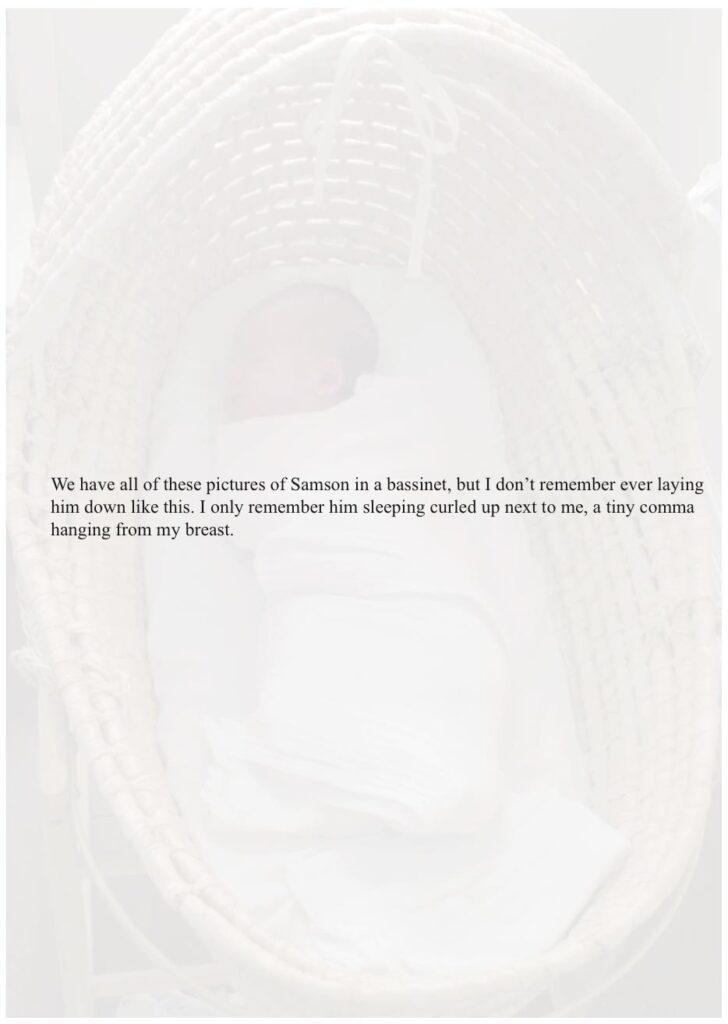

After dinner the nurse explained to me how you take care of a baby. What color their poops are supposed to be. How much nipple pain is ok. How I might feel cramping while nursing the first few days. Do you think you’ll need this? she asked, motioning to a little bassinet beside the bed. No, I told her, he’ll sleep right by me. The next morning we lay him on the bed so we could eat bagels and so Anna could pack. I lay there watching her shuffle around the room, shifted a little in bed. Where do you think you’re going, she accused me. I sat back. Can you hand me the camera? I asked. I have a feeling we won’t get a lot of cute sleeping baby pictures after today, I said.

Every day his sleeping face was more like my face. In the dark I could not see it next to me, but I knew it was growing more and more into the face I could have had. I look at pictures of me as a baby, lying on my father’s lap on the couch, lying in a stroller being pushed through the Brooklyn summer sun, and wonder if you ever knew you were photographing the wrong face, not your daughter’s face. Do you look at those pictures and see me? You all look so much alike now, you say, but you don’t mean my sisters. You mean me and Michael and Sean and Ryan. Your four sons.. The baby you’re photographing is not your daughter, I’d go back and say. Don’t say that name, I’d tell you. Say your baby’s real name. I’d whisper it in your ear. The photograph will come out better in the end, I’d say, if you say your baby’s real name.

I always knew how happy it would make my mother to see me pregnant. When I met Anna she told me it made her sad, how my life would always be hard now. My mother still thought I was her daughter then. Often other trans gestational parents I know ask how to handle it when family members won’t stop calling you Mom, wishing you a happy Mother’s Day, even calling you your old name after years of studiously avoiding it. People see you as different after you carry a baby, they say. When my mother had a daughter, a daughter first, I am sure she thought ahead to this, to me sitting on stoops in the middle of our walks in my Philadelphia neighborhood to catch my breath. To folding tiny newborn sized onesies into a drawer. The enormous globe of me, full with her grandchild. So much possibility there, that I could really be the daughter I was supposed to be. I thought so, too. When I sealed my ultrasound picture in an envelope and sent it to her, I felt happy for a minute, like maybe I didn’t need to transition to be happy with this body. But after he was born Samson only made me surer: his face a copy of mine, of my brothers’. He lay there with the life ahead of him that I wanted for myself, if he wanted it. Nothing about being pregnant made me feel feminine. This body is what it is: not quite man, not quite woman, but with the parts to create and shape life. To expel and care for that life. Creating Samson, named such a strong name because I felt I had done something strong, made me ready to be me. The best name in the world, Anna says, though we have two other sons. Your best present, she says.

I encouraged Anna to take a shower, to take as long as she needed. I told her I had it under control. I put on jeans for the first time since I’d had the baby, put a big stuffed walrus pillow on the floor, limped over and sat. When she came downstairs, she grabbed the camera.

It is good we took so many pictures because I remember almost nothing from those early weeks. I remember the new iPad Anna bought me—my push present—and how I watched endless hours of television in bed, nursing a half-sleeping baby. I don’t recall what I watched. Crime television, probably. Rapes, stabbings, murders. My choice. I inherited a love of these shows from my father. Each episode beginning gruesomely and ending with a clean resolution, the calming rhythm of imaginary killers and detectives. With Anna, it had been The West Wing, Sean’s long head turning towards the opening theme each time a new episode began. I think he knew the theme song from before he was born. Hours of White House staffers talking and talking, walking down the halls, how did they all talk so fast all the time? With my baby, I couldn’t sit on the couch; otherwise, Sean would scream for my attention, throw toys at me, steal my lunch. I couldn’t move fast. I’d had a tear. So I spent most of the day upstairs, in bed with the iPad and sleepy Samson. I was so sore that Anna, the nurse, froze medical gloves filled with water, wrapped them in gauze, and handed them to me to stick inside my underwear. Padsicles, I later heard a woman call them. I had stitches. Samson had been born after only six minutes of pushing. With Sean, I supported Anna through endless hours of pushing, but with Samson, I remember standing up out of the bathtub, yelling for help getting out, the rush of the midwife pulling gloves and a mask on. This is really good, Anna said after the first push. Oh shit, this already burns, I said, and then he was out. Born in a bathroom just before dinnertime. My stitches itch, I told Anna, days later in bed. That’s what they do, she said. What if they’re not healing right? I said. I mean, I’m happy to look. Won’t you never, I said. You know, I said. Are you kidding? she said. You know how many gross things I’ve seen. Don’t call me a Gross Thing, I said. I wasn’t, she said. I definitely wasn’t.

These are the things I remember. I barely remember Samson, or how he was like or unlike my other children, who Anna made. He slept more. He’s asleep in every picture. When I look at pictures from that time I can’t believe how young I look, how large and full my breasts were. Before pregnancy, I had perfectly round A-cups. In those early weeks, they grew to DD size, stretched, pulled, kept growing no matter how horrified I got. No baby could possibly need this much milk, I thought. My nipples were red and puffy, many shades darker than ever before; the breasts had purple stretch marks everywhere. When Samson cried, they leaked. When Sean cried, when he screamed at me as we played together on the rug, they leaked too, though he had never lived inside me, never nursed from me. I sat on a giant walrus pillow because I was torn up. Now, after pregnancy and nursing and years of testosterone and binding, my breasts are a ghost of what they once were, empty, floppy sacs. My stitches healed perfectly just like Anna said they would. This looks perfectly normal, she said. Normal: transgender, postpartum, in bed hiding from a screaming thirteen-month-old, hiding from having to leave the house, my floppy belly, giant breasts. No one would call me Sir like this, not ever. In the grocery store the older woman at the checkout laughs at how I pull out my ID at the same time I present her with a bottle of wine. You knew that was coming, she says. Where do I find the birthdate on this thing? she asks, searching my license. June 27, 1987, I say. I know I look young, I say. Damn, she says, you’re not kidding. You’re thirty? When I take my shirt and my binder off at night I see this aged chest, used to bits but still here, I don’t remember anything about the baby in the pictures, only the self, who I was then, just trying to make it through another day in the absolutely wrong postpartum body.

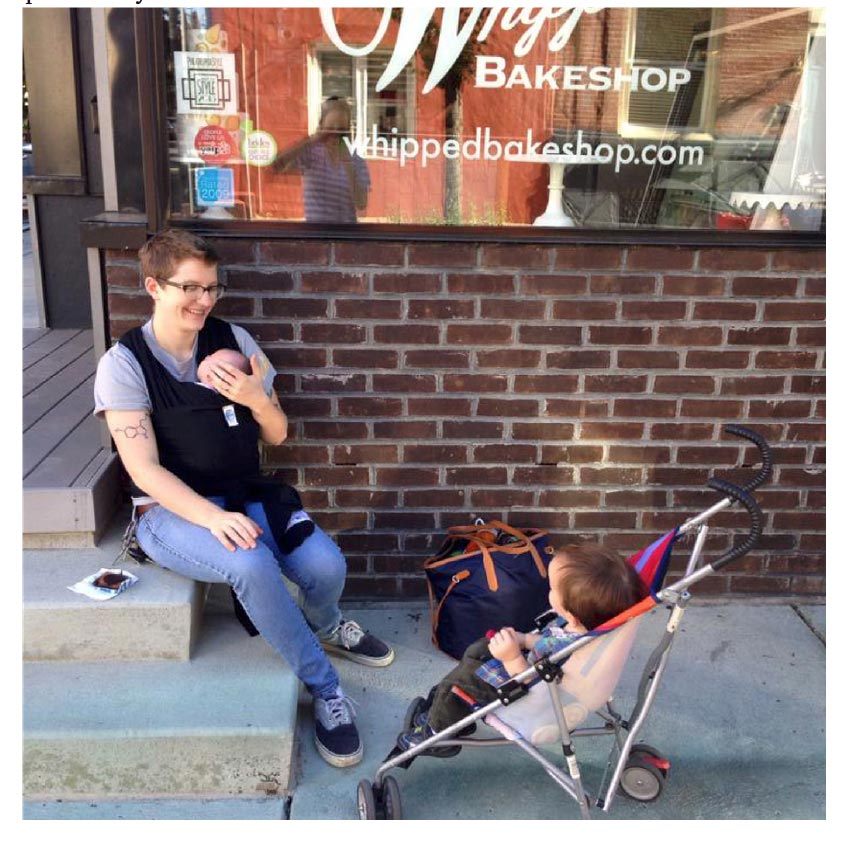

Wait, she said. This is exactly where we took that other picture. What picture? I said. You know, she said. The other one. The other time we came here to get brownies. Just sit right there on that step, she said. She parked Sean’s stroller beside me and Samson. No, Sean, you can have the brownie in a minute, she said, stepping back into the middle of Belgrade Street, holding up her cell phone. Don’t freak out, Sean, you’re going to get the brownie. Just let me take one picture of your Krys just like last time.