Museums of Natural Histories (1)

by Beth Marzoni

I was looking at a human body, a woman sliced in cross-sections no more than an inch

thick and pressed between glass so that curious people like me could see our insides up

close and personal, learn how it all stacks up. This, of course, is expensive but standard

science, like drilling into glaciers or carbon dating. You can tell the age of a tree by

counting its rings, but first you have to cut the tree down. These sorts of experiments are

irreparable; we call it knowledge. This is because rebuilding takes so much energy and

such incredible concentration—much like forgetting. My friends who have had children

cannot remember the pain of giving birth. When they talk about it, their eyes go wide as

if to say Isn’t it a miracle? If cut or broken, even if just bruised, the human body can only

heal during sleep.

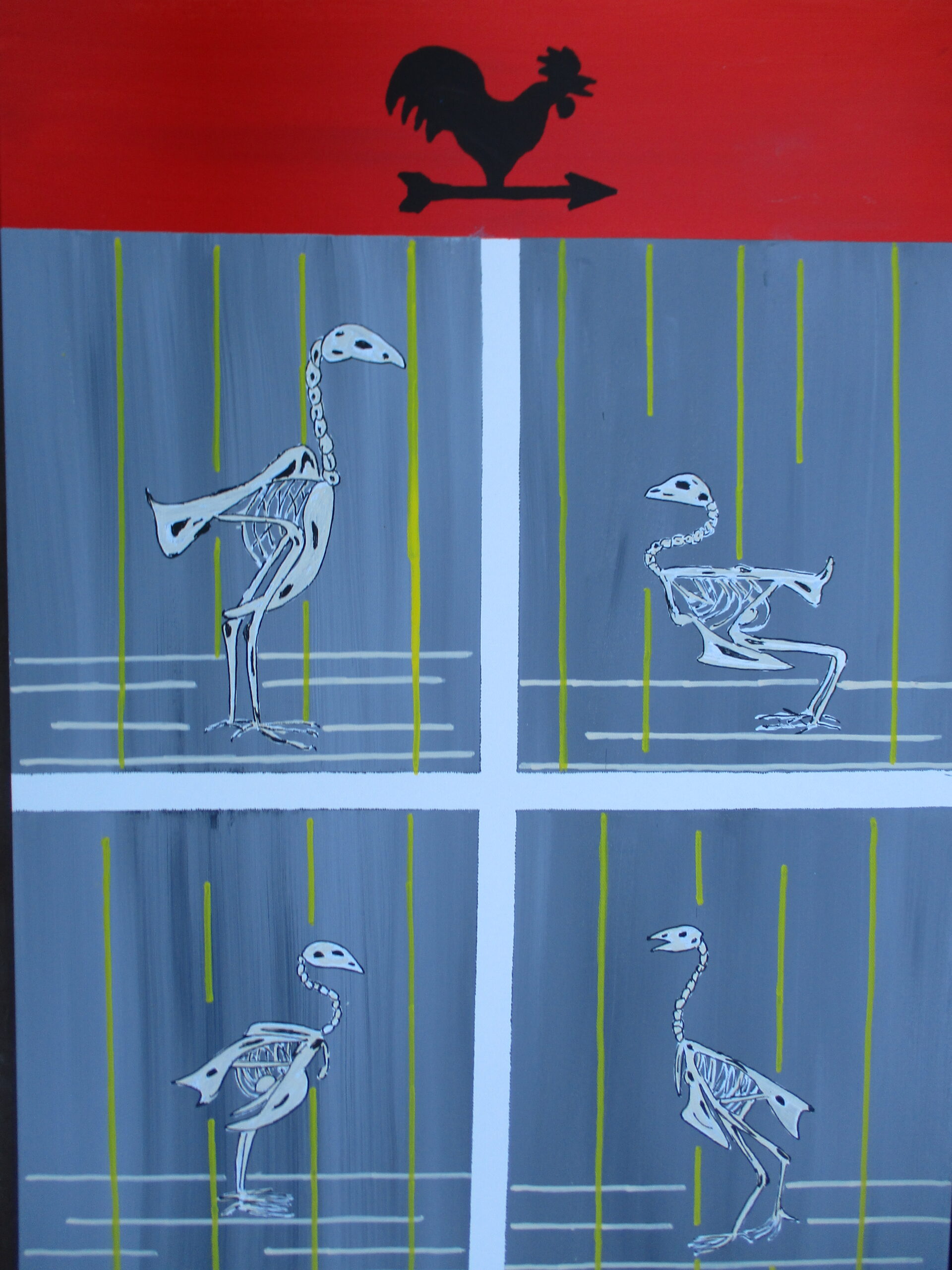

Museums of Natural Histories (2)

The penguins next door would have been the better choice

what with their slapstick waddle and pratfall routine,

or the god damn dolphin show though it’s embarrassing

how those creatures scientists say have language and sex

for pleasure—real wired brains—jump through hoops

and wave at the crowd smiling it might just be at us.

Better to be the butt of that joke than this one:

dead on our feet in this baggy hall of bones

staring up at the gaping hole in a T. Rex skull

where its left eye once sat, how distant, and how dismal

its slow death is thought to have been—starved

by the invasion of an ancient single-celled parasite—

and the imagined deaths of all those like her by drought

or by dust or a really big rock that fell

screaming fire from the heavens and Lord, I’m already

bordering on depressed. I’m not scared of dinosaurs,

my friend’s son says, but I’m scared of their bones

and Where did all their skin go? and How

could we put it back on? Someone should. They look cold.

His mother tells me the rabbit at school is sick,

and her boy’s got himself tied up in knots trying

to size up death so even outside the museum it’s hard

to forget time or its knocking on our bones, hard

to forget all the ways that grief may corner us

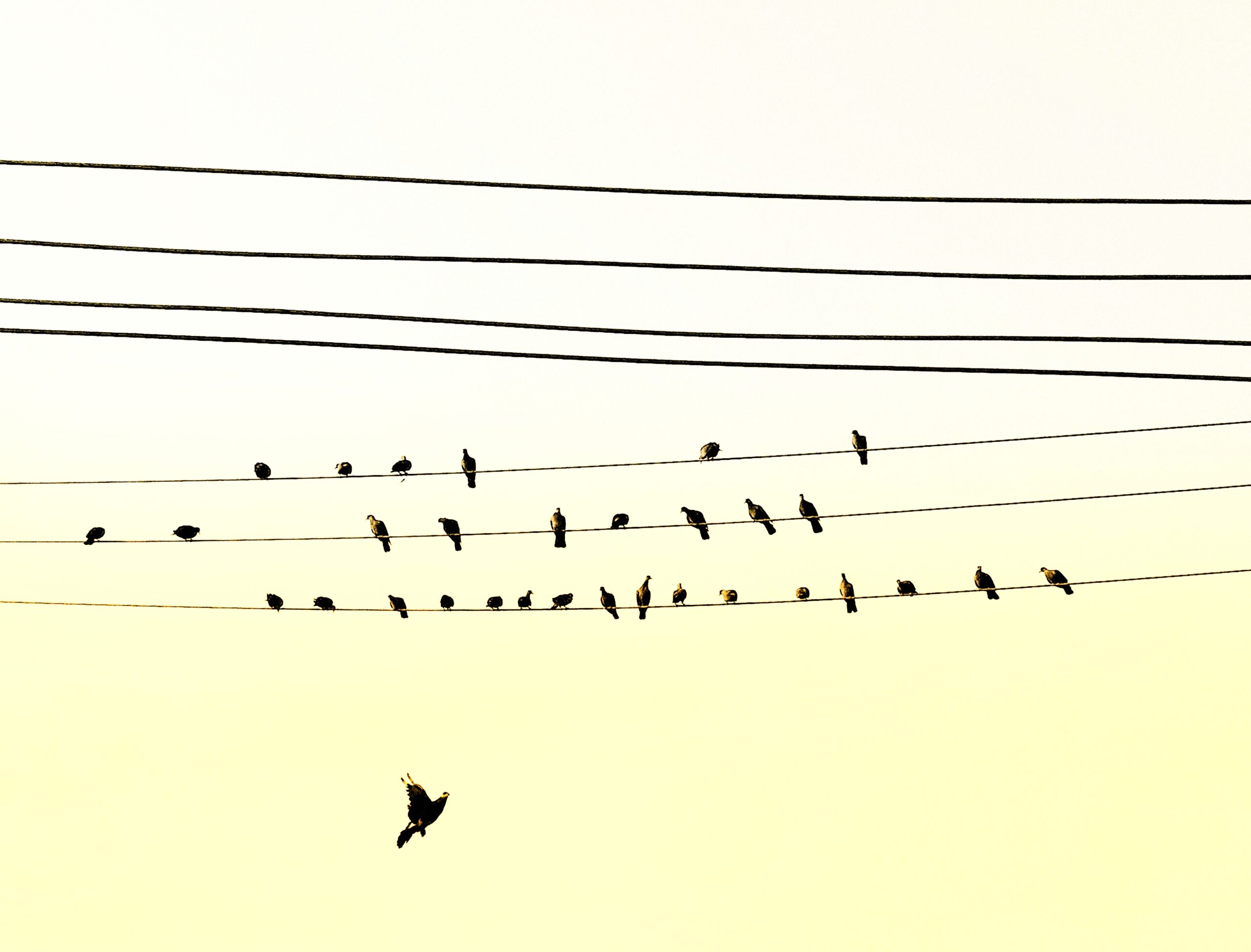

in the city—its music today no longer so indifferent,

but following us, following us: racket of the train

and the cabs, the buskers and the flashing, emphatic

warning chirp at the crosswalk—the signal for the blind

who know better, that’s what mythology teaches

us, the blind who know the streets by touch,

have learned to measure it all against their bodies.

Isn’t that how we know anything? By holding it

in our minds as we would in our hands? And tapping out

the fault lines, the dangerous foot-fall, the sudden

edge that could drop us to our begging knees?

I wanted to tell my friend’s son her name

is Sue, the dinosaur, and to take hold

of her, a bone in her foot, leg, anything in reach—

admonitory signs be damned—I wanted

to tell him the first time I held death I was startled

because no one prepared me, no one told me

how light it was and small in the palm, how that’s

the worst part: seeing what isn’t there.

He should know our eyes play tricks on us and how.

None of us wants to be a seer; Tiresias was always

a harbinger of doom who Tragedy followed

around as sure as the weather. I want to tell him

that once I met a boy who’d been struck by lightning

and lived, but the fire seared something shut

in him—the winding map of his nerves turned all

dead-ends by the short deep in his spine

or his brain. Or else it opened some deep and murky

emptiness up—no doctor’s sure what

happened exactly, but that now the boy has no

feeling. When he told me, I heard feelings.

Tell me: what’s the difference?