Backcountry Devils

by Jennifer Christie

She is ten years old and just stole—no, borrowed—her mother’s red pick-up truck for the day. Dirt from the flowerbeds is still on her hands, under the nails. The outdated phone books from the farmhouse’s kitchen have slid from the front passenger’s seat to the floorboards—the truck is so small she does not, it turns out, need them as a booster. Cornfields sprawl in every which direction, and if it weren’t the height of summer, she’d be able to see desiccated stalks disappear only at the horizon. Now, however, they are in full, towering bloom, and it’s like driving stuck in a maze. This is the way to Grandmother’s house.

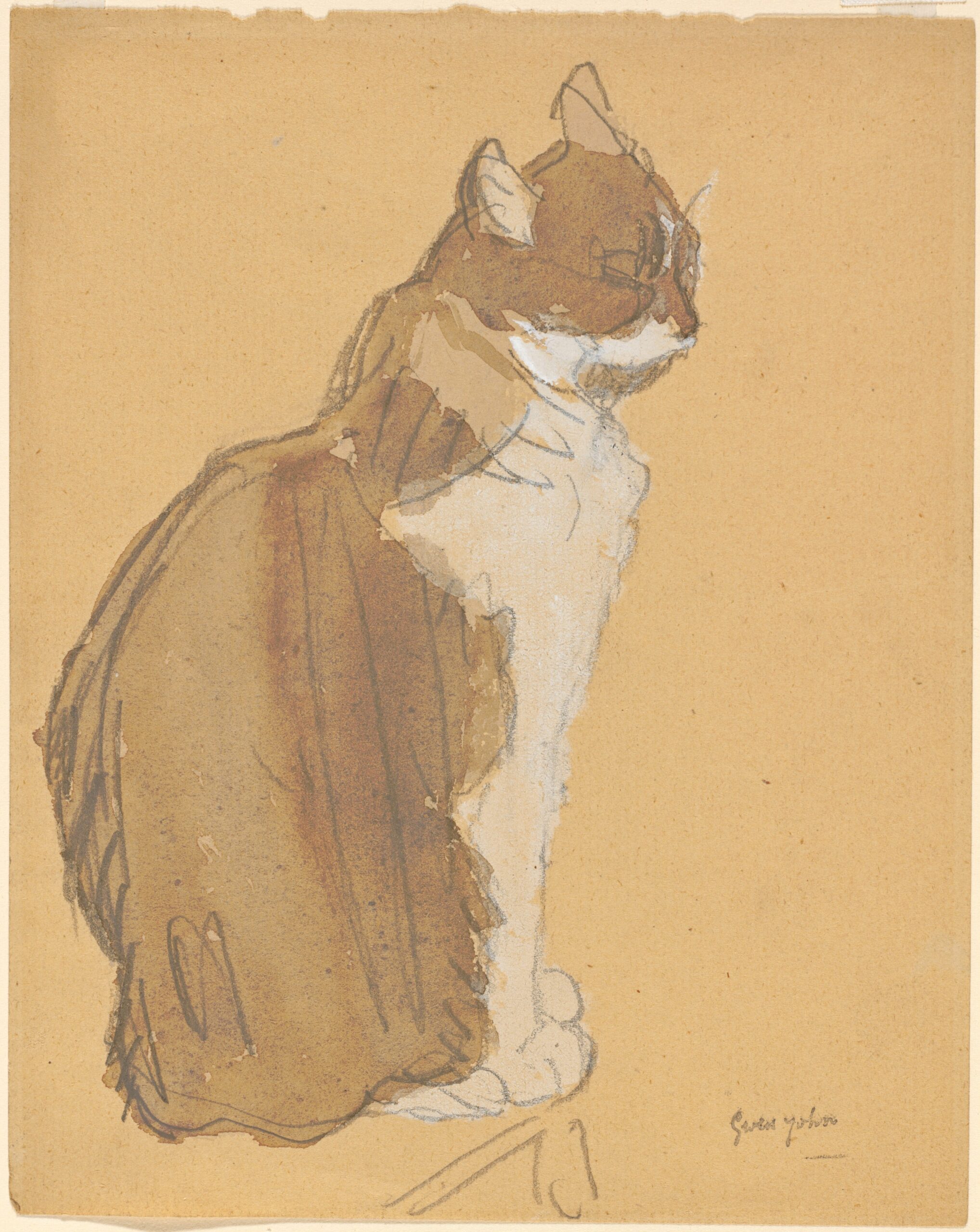

She should be worried about wild animals jumping out, but this fear is vague and mixed up in the confusion of being bad. Her mother told her to walk, but Elsa won’t—she’s in a mood. In the tulip stems she found a bird’s nest fallen from the house gutters, and the baby inside lay sprawled and bloody like a skinned mouse. The cat must have toyed with it before biting the head off. The naked wings were bloody, and the translucent skin seemed to have secreted a pus. Plus, Grandmother lives on the other side of Pleasant Plains. They can only drive, it’s miles away, but Mother probably doesn’t remember that. She’s been forgetting everything off and on for months—what day it is, the name of cat, when to do laundry. And that horrible cough, wet and phlegmy. But Mother doesn’t trust doctors, either—says black licorice should do the trick. Doctors are devils in disguise.

A mama deer and two babies materialize from the stalks and dash across the road. Elsa swerves the truck, closing her eyes, squishing the brake pedal with her toes in a reflex. The truck tips into a ditch and quivers, stuck, shaking Elsa’s shoulders. Her heart is in her throat, pulsing mightily. After a long minute, she opens her eyes and looks over the steering wheel. The car’s nose is kissing a small, white cross with a wreath of azaleas drooping over the T.

In her mind, she can picture it perfectly: one baby lying broken in the middle of the road, blood smeared in a streak to the asphalt, its mother in the grass, staring at the sad curiosity. There’s a little turkey vulture silhouette up in the sky, making loops. Elsa cranes her neck and sees through her window the empty road, then turns the keys and the engine dies. Nothing crippled or dead out there. Breathing comes easier—however, she is sweating up her plain white T-shirt, and a drop slides down the back of her bare knee. Her black hair is making little curls at her neck. The inside of the truck is far too hot for the frilled jean skirt put on today. Everything is too hot mid-July in Illinois, always, all the time, every year. And what will Elsa say now? What will Mother do? What can she do?

Mother won’t even leave the house for groceries anymore. They’ve been living off what’s been saved in the pantry and what the two of them dig out of the vegetable patch. Sometimes Elsa secretly goes over by the flaking old barn and picks the wild strawberries that grow there for something sweet. For some reason, the Amish family, whose shop of jams, sliced meat, strange cheeses, and rocking chairs off by the highway come in their buggy and deliver a few provisions. This is where the black licorice, thin and bundled up like a spool of dark, sturdy string, comes from. Elsa used to go with Mother to their store and play with the store cat, or the ducklings out back. But she, like Mother, hasn’t left the house in ages. Mother has stopped giving her math lessons at the kitchen table—nor does she read out loud from the Box Car Children set of books—used and well-thumbed—in the hammock between their two big trees. Mother doesn’t call anyone, not even Grandmother. It’s getting worse the longer Father is gone. She sits by the fireplace, staring at the old ashes leftover from winter, and slowly eats the licorice, sucking it between her loose, cracked lips—coughing and spitting into a cup, sometimes leafing though wafer-thin pages of the Bible. Elsa stays in the garden all day, playing in dirt, popping green tomatoes into her mouth before they ripen. She plays with the cat, but it scratched her the other day, and so she’s still mad about that. The red line goes all the way down her inner arm to the wrist. It was time for a change when Grandmother called. Something about her hip. Mother refused to go, hunched up like a toad. Like the toad Elsa’d seen by the summer squash blossom yesterday, dark against the sunset-orange bloom, struggling with a fat slug.

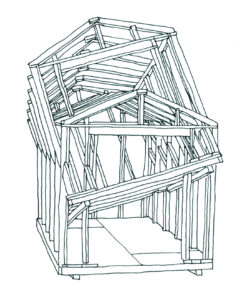

Elsa opens the truck door and more hot air from the asphalt pours in, but at least it’s a breeze. The truck is half off, half on the road, but it doesn’t seem like anyone ever comes or goes this way. Up a bit is a wooden building with a big sign that reads Midland Inn. Elsa knows this because she’s seen it every time she drove by with Mother to Grandmother’s house, when they used to drive. She doesn’t know what it is, but it’s the only place nearby, and it’s not far, she thinks. So she gets up and slams the door shut, staying off the hot road and walking in the ditch. Little bugs fly around her ankles, and she swats at them every few steps.

Soon the sign is rising above the corn, and then she’s in front of the squat wooden building, and begins to feel shy. But the heat is unbearable, and plus, she’s done something and she needs a big person’s help to fix it, and she doesn’t want to go back to Mother, not yet, not yet—

Two trucks bigger than her own, Mother’s, are parked in the gravel lot. She walks up three creaky steps, tiptoes the rest of the porch to the door, and pushes it open. The cool air pools out in waves, and it feels like tongues. She goes all the way in and gently shuts out the hot air. It’s so dark her sight goes fuzzy, little pink and blue circles dance in her eyes. It’s a restaurant, she sees, as the circles fade. There are tables and chairs and some benches, one with an old guy slouched down, asleep. It’s silent, except for his snoring and then clink—there’s a big man with a huge beard wiping out a glass mug, setting up a row on the counter before him. He’s staring.

“Can I help you?” he asks. Clink. He puts his hands on the counter and leans large shoulders over.

“Um,” she says.

“What’s that?” He turns an ear her way. The tip points through his hair like a dog’s with wolf in its blood. He’s pretty hairy. Elsa wonders if he can’t hear through all that bushy hair. She scratches a freshly formed bug bite on her elbow—her funny bone, is what Mother calls it, would call it. “Come in and sit,” the man says when she’s done scratching. He points to a tall stool at the counter. His lips are shiny, a little bit wet.

When was the last time she spoke to a man? Not the Amish men, they were quiet, though they did like Mother. Elsa went to the soft animals in the yard, though, too shy to say anything herself. Father? Dead for two years now. Heart stopped, Mother had explained the morning after, in her sky-blue apron, back when she used to wear the sky-blue apron. Could it really be that long? Elsa climbs up the stool and plops down on the seat. The man frowns wet lips nestled in the beard, but it’s the kind of frown, Elsa senses, that is actually a smile. Father would do that sometimes, like when she didn’t tidy her room before dinner—he didn’t care, that was something Mother used to fuss over. Nothing worth fussing over now. Neither clean anymore, which was nice, but now, she’s decided, is not nice. She smiles at the man and puts her fingertips on the cool, wooden counter. Everything is wood here—the woodpile by the barn. She looks up and sees a flying duck mounted on the wall—green and brown and surprise bits of orange in the feathers. But it’s dead and nailed like that, it’s not really flying.

“What can I do you for?” the man asks. The words are easy, but come out slow and he looks at her carefully.

Before she can respond there is a grunt and snore from the bench. The sleeping man moves, rolls, crashes to the floorboards, and the half-full glass of drink totters on the table, sloshing everywhere, but does not tip. He continues snoring on the ground. Elsa realizes her heart is pounding again. Sometimes she wakes up from Mother groaning loudly in the middle of the night—she sounds just like that man on the floor, like she is full of something not herself. She tosses and turns, moans like a ghost. It’s scary, and that’s another reason why Elsa’s been out in the garden so much, playing pretend in the leaves—like she’s in the jungle, the cat’s a jaguar! Pounce!

“Don’t mind Pete,” the man says gruffly. “He apparently don’t know where he come from.” He puts his hands up in the air. “Big revelation of the day.” He frowns deeper, but says, “You want a soda?” Elsa nods. She hasn’t had soda since root beer floats. Father just back from the fields. “But you got to tell me why you’re here,” he continues, as he squirts brown, fizzy stuff into a tall glass of ice, eying her, black eyes moist and droopy as a puppy’s. The foaming drink puts on a show of dancing bubbles. She sets her hands against the chilled glass and feels a pleasant shiver run up her arm, beneath the cat scratch. She takes a sip and the sweat under her bangs feels like a cold, wet blanket, like her sheets in the middle of the night. But this is sweet, and she hasn’t had sweet since the small strawberries by the old barn. This is better.

“Glad you like it,” the man says. He won’t smile, and she wonders if this—her being here alone—is all right. He is, after all, a perfect stranger.

Before responding, the door behind thuds open, slams shut. Boot sounds coming up behind on the floor. The man looks at whoever walked in, the person pulling up a stool a few down the bar. Pete groans again in his sleep. Elsa looks in another direction, shy, and sees, to her surprise, a big deer head on another wall, a little drip of black in a frozen trickle at the mouth. Old blood? She thinks of a deer by road. Mamas leading babies into the road—

“You have Sam Adams on tap? I’ll do that.” This is a woman’s voice. Elsa turns away from the deer head to stare. The new person has orange-red hair down to her slim waist—it’s the exact same color as a tomato when its finally ready to eat—when it tastes almost as sweet as the strawberries. She’s wearing big, black boots with a thick heel, but her jeans are tight around her legs, which are long and nearly touch the floor, even when she sits in the tall stool. Elsa’s own legs dangle foolishly, she thinks. She stops waving them about and stares at her soda again. It never stops dancing.

“Is this your daughter?” the woman asks, and Elsa knows the woman must be eying her, and she feels her cheeks burn to her ears. This voice is low, but smooth and sweet at the same time. Not like Mother’s, which is also low, but creaks and cracks. It’s ugly, Elsa realizes. Her mother’s voice is ugly, and matches the lips it comes out of. Elsa wonders if she has Mother’s lips, and feels her stomach cramp with a bad feeling so dark, she should feel ashamed. But maybe Mother isn’t Mother anymore—whatever that might mean—and maybe that’s more awful than she, Elsa, really knows. She can’t drink her soda. The man draws an apricot-colored liquid from a handle, and the glass fills slowly, frothy. Root beer float, Elsa thinks. The woman scoots up beside her and the man is saying, “Nope. Came through right before you. Don’t know her story, yet.” Elsa feels all their eyes, deer head included, as she studies the countertop.

“What’s your name, sweetie?” the woman asks, leaning down, close. Her breath smells like mint leaves, like the tea bags in the pantry, and the fresh little leaves Elsa keeps in pots on the porch. Her hair smells like—like—like the honeysuckles by the mailbox on the road. She looks up, and the woman’s lips are red, redder than the man’s slim wet ones. Strawberries. In her mind—she can’t help it—flashes the toad by the orange squash blossom, that toad that didn’t belong there at all. But she’d picked it up and kissed it anyway, feeling sorry for it, and now a frightening thought comes to mind—what if she’s cursed? What if she—turns into a toad someday, sucking in slugs and worms and whatever else? The woman is speaking again.

“What you drinking there?”

“Coke,” Elsa says. She thinks it’s Coke. Not root beer.

“You ever put cherry syrup in your Coke?” the woman asks. Elsa shakes her head. “Get this girl some cherry syrup, man,” she calls over the counter. “And put the little cherries in there, too. At least five.” She takes a sip from the big glass. It fizzes and dances like the soda, a lighter shade. The man sets a small glass of cherries on the counter and motions to it with a big, open palm, as if to say, “Have at it” with no words, and then stands again, serious and huge. The woman sighs and smiles, unscrewing the lid, pouring some juice into the soda, and holds a cherry from its stem, a cherry so red, a red Elsa has never seen before. Cherries, she thinks, are dark like stones. These are like—well, she doesn’t know. She delicately takes and eats it. It’s the sweetest thing she has ever put in her mouth, sweeter than vanilla ice cream, sweeter than soda. It bursts on her tongue. She asks for another.

The woman sets the jar in front of her. “As much as you want,” she says. Elsa tastes the soda. It is—beautiful. She eats another cherry. Takes a sip of soda. Cherry. Soda. She can’t stop. The woman is smiling with her huge, red lips, and the man is crossing his arms. Strangers are better than home.

“Did you walk here—or are you hitchhiking?” the woman asks. “Getting rides from people?” Even when she tips her head back to drink she doesn’t take her green eyes off Elsa.

“She don’t look old enough for that,” the man says. Pete rolls over in his sleep.

“I’m ten,” Elsa says, defiant. That’s pretty old. Maybe she should have said twelve.

“I guess I didn’t do that until I was sixteen,” the woman muses, drawing skinny, pointy hearts with her fingernail into her glass’s frost. She looks like she’s daydreaming.

The man behind the counter is watching the woman. “How do I know you?” he asks.

“You don’t,” says the woman, and turns to face Elsa, leaning onto the counter and resting the weight of her head in her hand. “Where’re you off to?”

“I was trying to go see Grandmother, but—but—the truck ran out of gas.” She lies because she doesn’t want to speak about the mama deer and the babies and driving off the road. She’s heard cars run out of gas. The other thing would be a close call, as Grandmother or even Mother might have said. The woman puts down her heart-patterned glass, smearing some away with her palm.

“One of them trucks out there is yours?” She turns to stare at Pete on the floor. “Is that your daddy?”

“No!” Elsa says, “my father is dead.” She doesn’t mean to sound angry. But Pete is horrible. She stares at the jar of impossibly red cherries. “My mother’s truck is down the road. I walked here from there.”

The man behind the bar grunts. “Ten, you say? Already stealing your mama’s car and driving? Didn’t do that ’til I was sixteen neither. ’Mongst other things.” Elsa looks up and sees, for the first time, that he seems pleased. His eyes go back and forth between the two girls.

“You need to go home and tell your mama what happened,” the woman decides. “But wait,” she says, “did you ever tell me your name?” She looks from the man to Elsa.

“Elsa.” Maybe she shouldn’t say. But she can’t help it. She wants to.

“Annie,” and Annie holds out her hand, long, wet-cold fingers, to shake. Elsa takes them, and they are smooth, not knobbly and creased. Soft and smooth. The nails are sharp and shiny, the better to trace frost-hearts with. “You’ve got a pretty name.”

Elsa blushes. “Thanks.”

“Finish your drink, and we’ll go out there together.”

“You guys want,” says the man, “we all get some gas and put it in the truck, and I’ll drive her mama’s truck back, and you can follow and drive me back here.” He looks around the restaurant and sees Pete. “No one but Pete coming in. He’ll be fine for an hour.”

Annie takes in the last of her drink, cheeks flushed and lovely. But she rises. The duck on the wall behind her really seems flying, Elsa thinks. “Fine.” It’s all Annie says.

The three of them—man, Annie, Elsa—leave snoring Pete and the cool inside for the hot summer air. They ride in Annie’s big, wide car that looks like a boat almost, like a sailboat Elsa has seen in an old National Geographic magazine her father had a subscription for, the pile by the fireplace. They sail on to a gas station down the backcountry road, the three of them like a little, strangely compiled family, and she watches from the car window Annie and the man disagree over who will pay for the gas emptied into two big red buckets looking like the watering cans on the porch at home. The man pays, in the end, putting his paw of a hand on Annie’s shoulder, saying something Elsa can’t make out, Annie nodding. They look at Elsa in the car. She feels embarrassed, like she’s intruding, and examines her shoes. The smell of gas trickles into her nose. Then all three are driving back to her mother’s truck—old and flaking and rusted, just sitting there near the cross like a dead animal. Elsa blushes again. The man gets out and begins to pour the gas into the little hole in the truck, a big shadow looming over an oversized toy. Elsa is inside the car with Annie, wondering if gas will start spilling onto the road.

“Can I stay in here?” she asks.

“You mean when we drive back?” Annie stares at her from the front seat, eyes wide and green. Elsa nods.

The man comes back over to the girls in the car. “You just left the keys in there like that?” he asks. He’s squinting at Elsa. “That’s not bright.” He turns to Annie. “Gas wasn’t at empty.” They both stare at Elsa in their curious ways, and she pretends to know nothing by saying nothing. Annie reaches her tan arm toward the backseat and rests a hand on the inside of Elsa’s elbow, squeezing, her nails digging carefully into the flesh, pinching the bug bite.

“She wants to go back with me,” Annie says. “She’ll give me directions, you can follow.” The man nods, slow, eyes steady on Annie like he might want to say something more, but doesn’t. Maybe—Elsa thinks of her storybooks—maybe he’s in love. She understands.

They drive just like this, the car leading the truck, the windows down. Annie tells Elsa to climb into the front seat and then turns the radio dial. Elsa stares out at the world, flushed with sunlight, blossoming all around, the wind in their hair, forgetting Grandmother and her hip, arm still tingling from the pressure of Annie’s nails set delicately in her bitten skin—and realizes the radio is not playing crackling static or a crinkly voice giving a sermon about devils. This is what Mother plays, or would play, if the house radio were on at all. And her father, when he was alive, liked to read. They didn’t have a television, either. They didn’t even listen to the radio much. But this now is something completely different, and the sound is flowing into her ears. It feels like what honey looks like when it falls from a spoon into her tea. Smooth and lovely. She has never, not once, not ever felt this in her ears, her head, her chest before.

“I like violins, for some reason,” Annie is saying. “Maybe my mama played this kind of stuff to me when I was in the womb. I don’t know. That’s what I like to think.”

Violins. Is that was this is? The corn is flashing by as they near the farmhouse. Elsa doesn’t want to tell the truth to Mother now, doesn’t ever want to go home. The ugly toad by the squash blossom—the toad by the fireplace, sucking up black string, never playing the radio right! This radio sound is like the crickets at night, rubbing their legs together up in the trees, leaves clapping in the wind, like hands. But better. Sweeter, but not on her tongue. They are parked in front of the farmhouse. The man is getting out of the truck and heading slowly for the porch. She could stay like this forever, with Annie in the car. She sees Mother in the window. She sees the cat on the sill licking its paws.

Elsa doesn’t move. Annie turns off the car and the radio dies. Elsa knows she’s about to get out and help the man explain to Mother what happened. But Elsa doesn’t move. She’s thinking, quickly, about the baby bird this morning. The one without the head, the scratched and gnawed at wings. Mother has locked eyes with her through the living room window, and Elsa is staring through the windshield, and Annie is asking her if she’s all right. But Elsa doesn’t respond, doesn’t move, and all the sweetness she saw and tasted and heard today disappears. For she sees a little black trickle coming from the corners of Mother’s cracked lips, and she thinks of the baby deer, and then the baby bird, and she thinks of those cracked lips, and she knows, for just a second, she just knows it wasn’t the cat that got to the bird first.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jennifer Christie is a recent graduate of the MFA program at Oregon State University. Her master’s thesis (a short story collection titled The Four-Chambered Heart) won the 2013 OSU Outstanding Thesis Award, and in 2012 her short story “The Festival” won the Salem College International Literary Awards’ Reynolds Price Fiction Award, judged by Kate Bernheimer. She currently lives in Corvallis, OR where she teaches, tutors, and writes.