Dear Birthplace,

by Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach

January, 2014

Dear Birthplace,

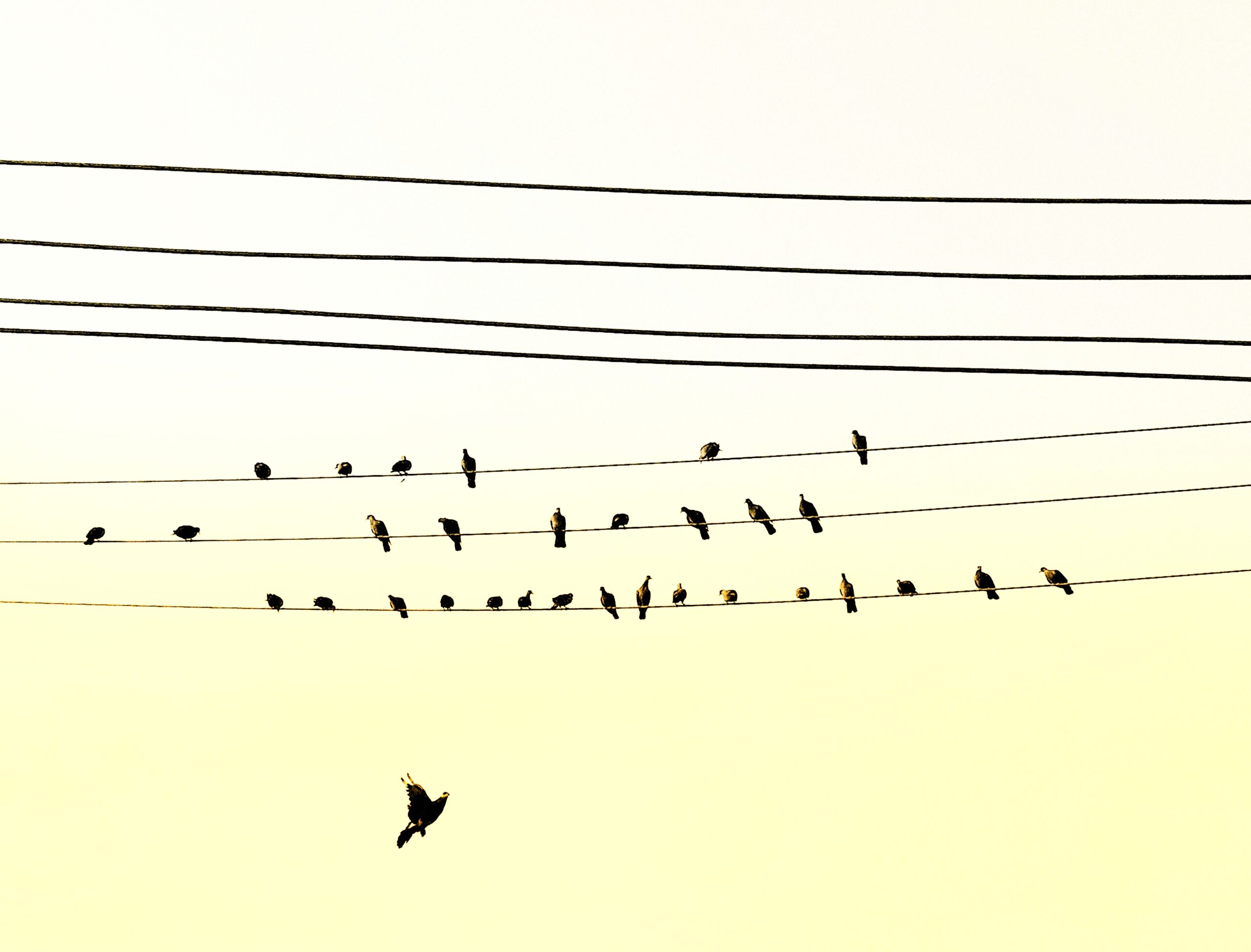

In 1993, the USSR had already collapsed, I was already six-

years old, and you were already a sovereign nation. Only then,

after years trying to flee, my family was granted Jewish-refugee

status and allowed to leave you, Ukraine, never to return or

regret leaving.

I remember little of your then mostly Russian speaking

Dnepropetrovsk. My Rodina, birth-city, homeland I never

knew as home. I recall the sausage and Kvass street-vendors

we couldn’t afford; the rusting fountains I walked when the

river flooded; the hours in line, waiting for bread and eggs and

milk and tomorrow; and the neighborhood boys, who once

threw stones at me because I was a little zhid girl playing on

their street. And this, I thought, this was trauma. And our final

departure, that rain-drenched winter, a break from the

language and world I was just learning to read, this was trauma

too.

But today, when my American soil is covered by heavy-white,

Soviet-like January snows, while Kiev’s streets are melting,

rutted with fire and ash-tarred bodies, I know that I know

nothing of your trauma.

When the police are shooting and beating and tearing into

your own people on their own streets—brother’s body against

a brother’s against their mother—I can’t begin to know your

unearthed demons, the death sinking into your once envied

chernozyom with the hope of leaving roots.

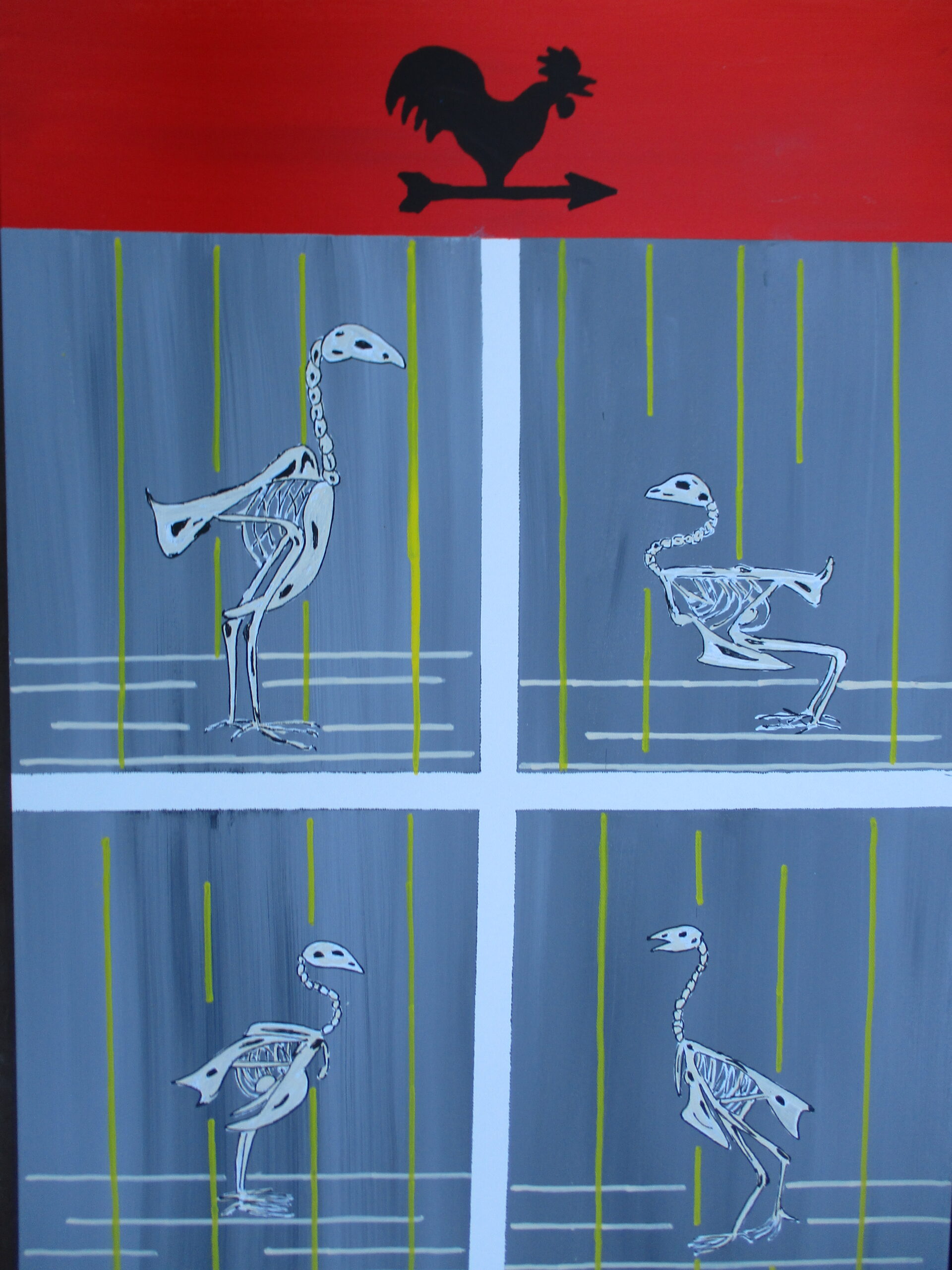

Can’t begin to understand what violence mutilates your body:

a starving tree grown wild and violent: a cracking flesh that I

believed was once my country.

And I close my eyes, try to think harder, to remember or

imagine it, that ghost elusiveness of you. But I recall only the

train ride to your capitol city, and the hardboiled eggs we

pealed while playing cards on the top bunk. Too young to

understand them then, the games, the very gamble we were

taking.

We won. I know that only now. But I have lost the way to

place the place of you, of motherland, inside my mind. I want

to remember Kiev’s central square, Maidan, standing there

before its fountains or seeing it shrink below through the

window of an airplane, but nothing comes, and so I watch a

recent video of a journalist hit with a grenade amidst the

burning barricade and faceless military men. And that square,

that you, is somewhere in the background, lost in all the

smoke and panic: first aflame and then a grave.

I read the news, watch footage of “medieval violence,” as one

reporter called it, but feel only pressure. An iron lung, the

weight of memory or its lack. The fear of losing people and a

country.

Not mine, its someone else’s wound,

Anna Akhmatova whispers.

And in writing myself into your story, I know I am at fault—

an artful imbedding, a weed trying to thrive in an estranged

history.

So instead, I’ll go back to Caruth and Freud, and all their

distant trauma theory. I’ll watch their pages thin to legible skin,

but turn meaningless in the face of what is real and

indescribable. In the face of “the trauma” I thought I knew,

the one I know I cannot touch. The too soon forgotten

foreign bodies bleeding in your own Slavonic name. A country

shattering like a red-gold teacup.

I try to carry it, this story. Try to write it across the Atlantic.

But it is yours, and yours alone. I have no right to it. Mourning

must be earned.

Forgive me, Rodina—ground where I was born. Forgive me,

rodnaya—my dear, my native familial flesh. And I’ll forgive that

you are not a motherland who grants forgiveness.