Interview

by M.E. MacFarland

“I prefer to be reminded that what I am seeing is not quite real,”

the famous photographer says, shifting portraits

with half-developed coronas into the bath and out while the reporter,

erasing a word, shakes her head at the caustic smell.

Dispossessed in the heavy red glow, she writes What better place than this

for insanity? Nothing feeds it like the eye. Unprompted, the photographer

says: “Everything I knew of gesture I learned by the age of nine.

Thereafter, I became concerned only with the space from which bodies

emerge, until I turned eleven, when I was taken to the ballet.” He pauses.

“Yes—to the Kirov Ballet. The prima, she—she was witchgrass against skin,

evening’s vellum over the steppe, an azimuth by which I might measure,

for the first time, the concept of God.” He turns away. “I cannot—”

Frustrated by memory, the reporter writes. She lifts a negative

to the red bulb, which casts shadow onto her shoulders.

“Can you imagine”—the old man suddenly turns—“another

silhouette to take her place?” His pale eyes long, as torn things do,

to once again be whole.

* * *

“The day’s frustrations leap and disappear like dust clapped out from a doormat,”

he says. He clicks through the carousel

and roseate color clouds the screen: a woman

looking over her shoulder at a man in a suit leaving the house.

The photographer gestures and says, “I consider this my mythic work.

Gorgeous fragments of love pass between them and they try

not to overthink their suspicious lives.”

A band of gold glints above the reporter’s notepad.

She writes creates narrative where there is none.

“Surely you have been in love,” he says. “Is it not unlike lightning

striking a tree, which for years after continues to grow but never blooms?”

He coughs and taps a cigarette out on his palm. “And isn’t it like

a holy city in the unnavigable reaches of some rainforest?

You can watch as the pilgrims give up trying to reach it.

The wheels of their covered wagons breaking on the roots…

their empty boots like islands in the mud.”

His lighter opens a flame in the dark.

“Though of course in the end one prefers ruined cities.

Have you ever woken to find yourself

in the ruins? They are always so familiar.”

* * *

Professes skepticism of Freud but loves to play the analysand,

the reporter writes. Her pencil carves the quiet morning apart.

She thinks of the recurring dream the photographer feigned

reluctance to tell: “I do not like dreams. They reek of self-importance.

But in this one, I am pulling a man by his shirt collar from a lake

that does not exist to a porch that does, where my family watches,

gaunt and strangely shining. It is winter—the trees have disrobed

to their shameless charcoal limbs. The wet fabric in my hand begins

to tear, and I wake.” Through the guest room window

she can see the gathered folds of conifers reaching into the low hills.

She writes, How does a sunrise define the day to come?

She walks to the kitchen and finds him

at the table with two mugs, staring at a pot of coffee.

She sits and writes Often lost in thought, a guest even in his own rooms.

She reaches for a mug and sips the coffee, which has been sweetened

to the point of nausea. He watches her cough it down

and says, “Every morning I consume the same pot of coffee, in which

is dissolved two cups of sugar. I believe it to be the closest

approximation to the nectar hummingbirds drink.”

He drains his mug in a single practiced motion.

Smiling, he says, “Your hand is trembling.

There is no cure for that

except becoming a hummingbird.”

* * *

Possible title: Lear Maddening on the Heath,

the reporter writes, following the photographer into the north wing.

Too oblique, but the gist is there. Soft, jaundiced light falls against

the polished boiserie of the hallway, above which

a series of portraits hang. To be born into this

kind of wealth is a sort of illness, she writes. The photographer says

nothing until they reach his studio, a spotless, white cube of a room.

She writes, If a cliché is taken to its logical extreme,

does it circle around and become original? He nods his head back

toward the hallway and says, “I never speak in that corridor. It is where

the dead reside. They are mute, and to utter anything

in their presence is gravely impolite, for they cannot respond.”

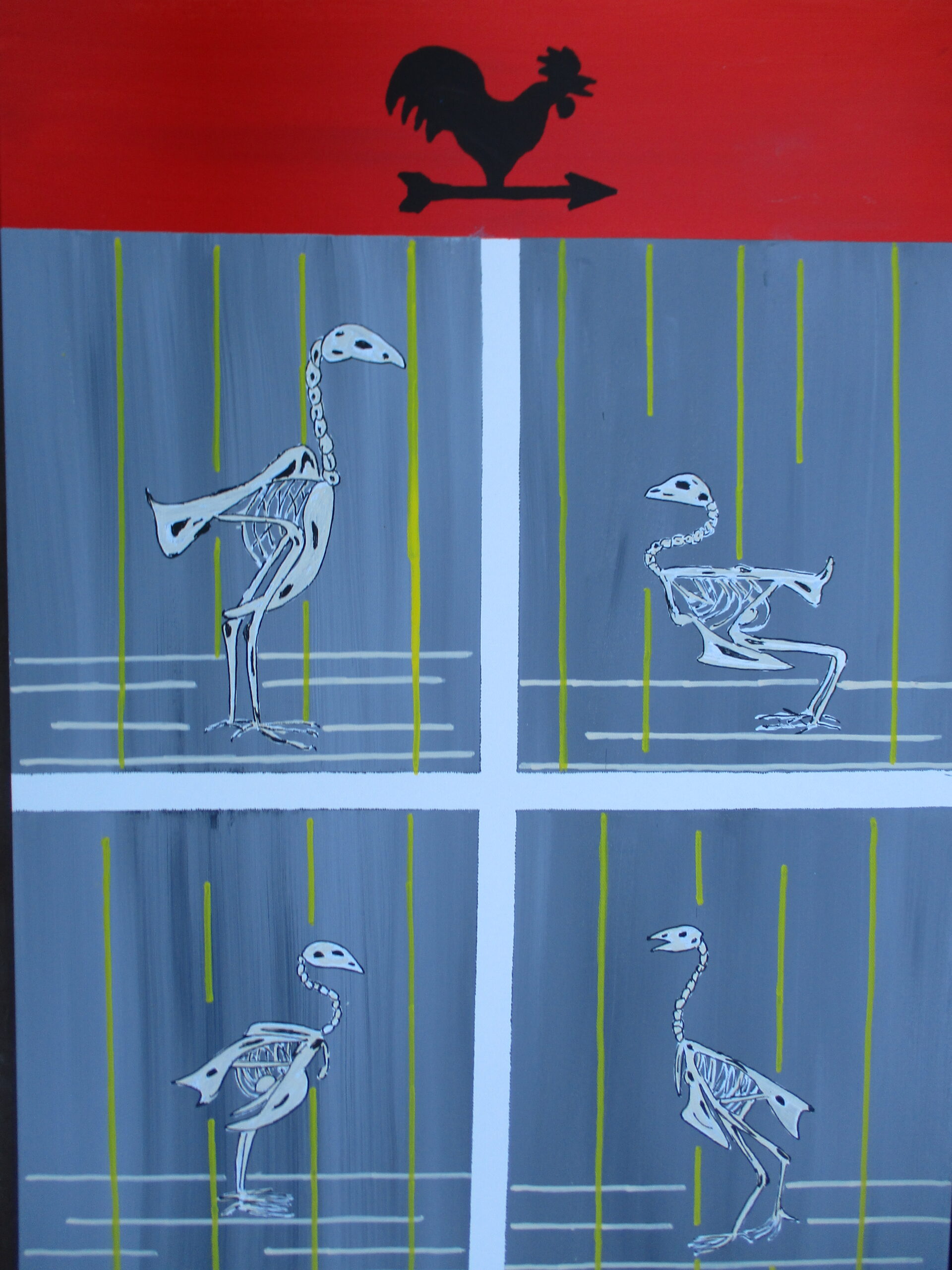

He turns, then stops and says, “Art, by the way,

is whatever we do to embellish death. Write that down.”

She does not. He walks to the center of the blinding floor.

“A week ago this room was red. Before that, lavender.

Before that, a painstaking damask. Each layer of paint makes

the room smaller. I intend to live to see the room disappear.”

Just inside the hallway, he opens a closet

where dozens of paint cans line the walls.

“Please help me,” he says, motioning toward them.

* * *

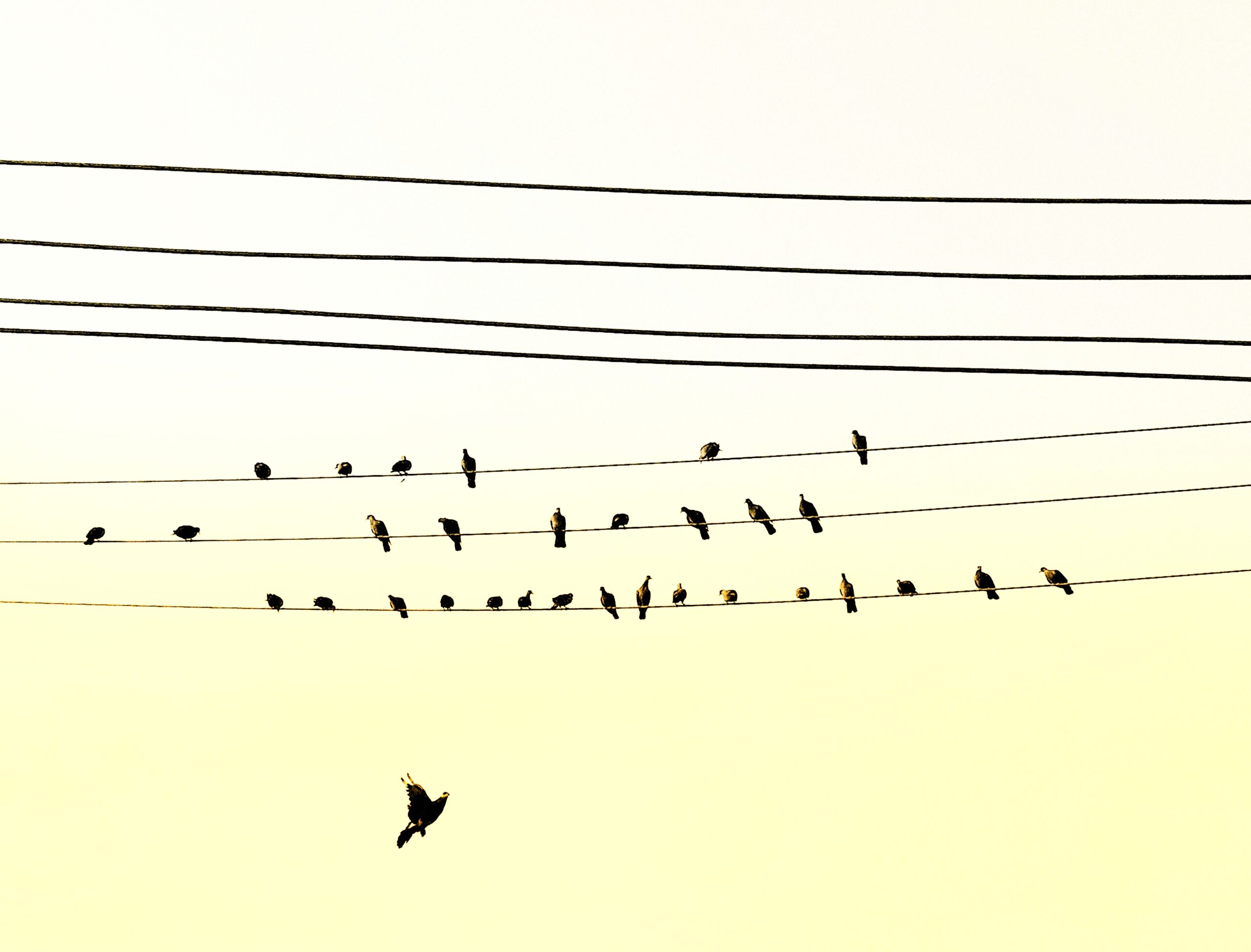

“After all, what is this adopted landscape if not lifetimes spent in the study of

stories?”

the photographer says. He nods toward the untouched trees

pressed tight to the balcony. “What does nature say that we do not

put in its mouth?” The air has a dull orange hue, as though the sun

were a lone piece of stage lighting left humming into the night,

forgotten as the actors depart to receive their roses in the atrium.

“Centuries ago wolves in Scotland would disinter graves during famine.

I like to imagine the villagers as sculptors,

patching the throats and jaws of their fathers

then burying them again on a holy island off the coast.”

The reporter writes Lover of counterfactuals, lover of the bright unreal country.

“Of course by 1750 the wolf had been hunted to extinction

in Scotland,” he says. “Nothing gray can stay, no?”

He runs his hand along the stonework. “And what of my kind,”

he says. “Will I be hunted to extinction? In what sort of light

am I to be portrayed?” The reporter’s words fade

as she writes; she shakes the pen and presses harder.

The light that quickens and dismantles, composes, suffuses, but does not—

The pen dies, leaving nothing in its wake. The photographer

rubs his eyes. The dark palisade of trees

moves casually with the wind and beckons.