Wolfy

by Andrew Joseph Kane

They used to stay on Dune Street when Dani was little, before Wolfy came around, but they were on Ocean now. Farther from the beach. Farther from the fun. Even so, summers in LeFay were mostly normal and good, even if they couldn’t always go out like Dani wanted. Sometimes Gabe would pick them up a pizza at Pizza Fredo, or they’d get some fudge from Jim & Jack’s. But they couldn’t go to the Sea City boardwalk to get frozen custard or funnel cake or cotton candy or anything really. Wolfy wouldn’t last long out there with the flashing lights and the loud sounds and the crazy people from New York City who didn’t understand personal space bubbles and would bump right up to you pushing a stroller or yelling at their cousin. Or their kids would act nasty in line like they’d never waited their turn to go down a waterslide before. Before Wolfy showed up, Dani loved riding the rides and running the boards and hitting the mini-golf through the gorilla’s legs. But now they never left LeFay which didn’t have a boardwalk or motels or other noisy fun like Sea City. Just a couple of roads and some food places and bicycles. But sometimes Dani felt guilty because she liked it wild.

One day on the beach, Becky brought PB&J sandwiches. Dani ate them under a blanket, so the seagulls couldn’t grab them. The sand on the underside of the blanket fell into the bread, but Dani didn’t mind—she liked the way it made a crunch in her teeth. She had to hide under the blanket because if she whacked at the seagulls with a plastic shovel or a twisted-up towel Becky would yell because she felt bad for every dumb thing. Which was why Dani couldn’t have hermit crabs or squish a spider in the corner of their house back home. It was why she couldn’t call Wolfy Wolfy. When Dani got angry, she just put up her middle fingers behind her back or in front of her chest depending on where Becky was standing because not everything was worth feeling bad over.

Outside the blanket, Wolfy was cooing and probably pinching grains of sand.

Are you singing, Rayray? Becky asked

Wolfy cooed a little louder.

What’re you singing about? Row row row your boat, Becky began to quaver.

She’s singing Duran Duran’s “Ordinary World,” said the lump under Dani’s blanket.

What?

Daddy sings it with her. She likes it.

Then Wolfy decided she wanted the blanket. Wolfy tugged it and tugged it, and like she was dealing with a little dog, Dani had to give in or Wolfy would hurt herself. Wolfy got what she wanted because she yelled and Becky yelled and other people started looking. Gabe was not at the beach because he did not like the beach. If Gabe was there, he would’ve settled them down and explained to Wolfy that Dani was using the blanket and that there were other blankets to use. And if she really wanted this particular blanket, he would’ve told Wolfy to say, Please Dani. Puh puh puh. Please. And Wolfy might’ve done Puh puh puh, but she definitely wouldn’t do Please Dani. But since Gabe wasn’t there, Dani dropped the blanket and went straight to the ocean and stood in place where the water fell in and then pulled back out. She faced the dunes feeling like she was going backwards in time, kind of dizzy looking down at the foam and her ankles until the next wave came in to suck itself away again.

After washing up from the blanket sandwiches, and since she had to pee, Dani walked out far enough to go. She liked the way the warm pushed around her legs. The boys out there were boogie boarding and throwing balls and carrying on, and she could see them see her now—the boys—and even some old farts with their bellies hanging over their waistbands. Big bellies, bellies bigger than pregnant ladies, but their arms still skinny and swaying. Smiling and squinting. Looking at their toes. Looking at Dani. Becky wouldn’t let Dani wear a two piece yet even though Teresa Maxman and Bet Crowley and a zillion others did, but when she finally was allowed, look out.

When Dani waded back, she stepped on something sharp. She squeaked and danced and checked her foot for blood, and then she saw the shell lodged in the wet sand. It was pink and pearly and in perfect condition, not like the shell shards that littered the rest of the shore. It was the size of a Christmas tree ornament, swirly-shaped, sturdy-feeling. She squeezed it in her hand and felt the sharp points prickle there. She squeezed harder then.

An old guy with chest hair like a gray rug was standing beside her.

Careful about going in, he said.

I just was in, Dani said.

The riptide’s real strong today. He waited for Dani to ask what riptide was, but Dani knew what riptide was. She was eleven and not some crumby dummy like Wolfy or Teresa Maxman.

Dani turned to go, and the man said, It’s cause they didn’t grade it the right way down to the sandbar.

Dani didn’t know what this old guy was talking about, so she said, When I was little I thought it was sand bear instead of sandbar.

And he said, Oh yeah?

And Dani said, Yeah.

He laughed real big, and even though his skin was old and brown, his teeth were big and new. He wanted to tell Dani more stuff, but she turned to walk away. All of a sudden, Becky was there with one of Wolfy’s little yellow buckets, and Wolfy was there too holding the matching yellow shovel. Becky looked at Dani and put a hand on her wet shoulder.

The guy said, So these are your girls?

Yes, said Becky.

I was telling this one about the riptide.

Oh? said Becky.

Wolfy started playing with the blue braid Dani wore on her wrist. She liked to play with that little bracelet and Dani let her because surprisingly Wolfy never wanted it for herself. Then Wolfy saw the shell in Dani’s hand. And she definitely wanted that.

The guy took a couple steps towards them on his big bony feet. He squinted his eyes and took a breath to tell them everything: Just that if you’re not careful—

Wolfy grabbed for the shell. Dani pinched Wolfy’s arm. Wolfy screamed. The guy was saying something about getting sucked away, but no one was listening.

Before Becky dragged them off, Dani threw the shell back to the ocean.

At the umbrella Becky said, I can’t believe you.

Old Man Riptide was a weirdo anyway, Dani replied.

That’s not what I’m talking about. Raylynn just wanted to see what you had—

It was just a stupid shell! Dani said.

Exactly! Becky was all elbows and eyebrows. She lifted her hammy arms up and the hams jiggled and bounced.

Dani said, Whatever lever, but it was under her breath which is the worst way to say anything because then:

What did you say?!

Why can’t I ever have anything that’s mine?! Dani shouted, but her head was fully under the blanket when she said this, middle fingers up, hard, thinking Becky can keep talking about how not everything in life is fair until she falls over dead.

Becky was not Dani’s mom and Gabe was not Dani’s dad and Wolfy was not Dani’s sister, but they all stuck together like a family. As far as Dani knew, she was just a normal orphan, not a news-story orphan like Wolfy. But sometimes she thought maybe her mom was a bank robber who wore Halloween masks and rode dirt bikes to flee the scene. Living in hotels with pools. Shooting security guys in the kneecaps. Laughing. Maybe she was a drug addict who sucked crack smoke through crack pipes like they showed on the graphic behind six o’clock news anchor Trisha Stephens’s big frizzy head. Maybe she smoked crack pipes all the time. Everywhere. In backseats and barroom ladies’ stalls. On smoke breaks propped up against the wall around the corner from the Dollar Tree. Or maybe she had cancer and sat in a chair on a porch with an old, old dog. Reading the newspaper and waiting. Or maybe she took one look at skinny baby Dani and just decided she’d rather not.

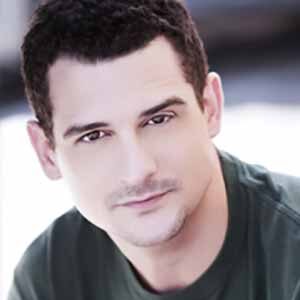

Wolfy was taken by a man named Cole Francis Diego when she was really little. He kept her in a basement all tied up until she was five. He didn’t feed her right or treat her right, and she never learned to walk the normal way or even talk which is why she sounded like a wolf most of the time. After the police kicked in Cole Francis Diego’s kitchen door, Wolfy had nowhere to go. Her real mother died of pills that were supposed to relax her, and her father was never listed on the birth certificate. Becky didn’t want Dani knowing any of that, but Dani looked it up on the public library microfiche instead of reading in the reading group with the boy who only wore Rush T-shirts and the girl who always ate candy necklaces. Dani told Becky what she had found out, and Becky was mad for about a week. Gabe sat her down on the green-brown armchair in Gabe and Becky’s bedroom and asked Dani if she wanted to talk about what that meant, if Dani knew what that meant. She looked at the black hair on Gabe’s forearm and the gold class ring on his hairy finger and told him it meant Raylynn was basically an animal, and that it wasn’t her fault. Gabe looked down his thick glasses and said that it definitely wasn’t her fault.

The next day Dani was determined to not let Wolfy get a chance to want something she had. So she didn’t eat her sandwich. She didn’t use a towel except to lay on. She didn’t go into the water, not even to pee, and she didn’t have to pee because she didn’t drink any of the juice boxes from Becky’s brown plastic cooler. She didn’t even ask to buy an ice cream when the ice cream man rang his hand bell from the dunes. She just put on her headphones and played her walkman, something Wolfy was never interested in.

She laid and listened and watched the muscle bums bounce a volleyball around and their babes bake and turn and bake and turn. The radios sang different songs, but they were far enough apart that they couldn’t break up her own special jam (Ace of Base’s “All That She Wants,” Alice Cooper’s “Feed My Frankenstein”). The airplanes hung low with letters flying behind them saying about the Juke Bar Dinner Specials and Try a Bud. Past the breakers, boats were boating past. Dani’s eyes shivered, closed.

She woke sweaty and hot. Wolfy was sleeping under the umbrella like a grumpy potato, snoring through her long mess of hair, and Becky was lying on her stomach flicking her toes. Dani saw her chance and stood, letting her headphones fall as she stepped towards the sea. Her joints made little pops and felt good, the hot sand underfoot. She squinted through the salt, eye corners stinging, hair sticking to any skin it touched.

Dani hopped across the tide, knee deep, then waist, then cut into the waves, smelled the briny funk, spat away the taste of it, dove again. Dove into the force of them, sand and other bits skitting past her arms, her legs, nicking her face. The whole ocean leaning into her, she pushed, she kept pushing. She blew bubbles into the churn, pulled her hair back, felt it tendril out when she stopped to tread. Hey, she heard. Hey!

Dani saw two girls waving at her from farther in, cringing and squealing when the remains of a wave crashed around their legs.

Hey Dani!

Dani wiped her face, the drips from her nose, her eyelashes. The girls giggled again and held their arms across their chests modestly. Dani let a small swell pull her further in to shore. The girls were stepping daintily in the foam.

Dani, what are you doing here?!

It was freaking Teresa Maxman and Bet Crowley. They both wore bikini tops though they were no older than Dani in her dark blue one piece.

I come here with my family, Dani said, blinking down at the girls. She felt like a caveman.

Get. Out. Teresa said. Since for how long? I don’t think I’ve ever seen you here.

Dani began counting in her head the times she had seen both of them in the past three summers: at Pancake Parade, on the swings at the 12th street park, at Magic Pier in Sea City on three separate rides: bumper cars, bumper boats, and the Screaming Cheetah Coaster.

Dani saw them see her legs. The length of them, their leanness, the water dribbling.

I love your bracelet, Teresa said, reaching out to touch the small blue braid that clung to Dani’s wrist.

Thanks. I like your—Dani studied them both. They were several inches shorter than her. Hips cocked, legs in third position, fingers curled. They both had eyes like glass beads, changing colors if they looked at you straight on. Bet was wearing peach colored lip gloss. On the beach. In the water. They were also wearing bracelets. Matching ones with letter gems. The letters spelled their names. In case they forgot.

I like yours too, Dani told them.

But then from the beach Dani heard her name, and there was Becky and Wolfy walking along the edge of the water. Becky was waving the yellow plastic shovel. Teresa and Bet turned. Dani watched her wolf sister, her wolf family, and clenched her jaw. She had no blanket to crawl beneath, no middle finger to burn away their stares. So she threw up a single hand, stabbing at the sky. Becky raised her arms, hams flopping, palms up, and shook her head. What does that mean? she mouthed.

So do you think you could make one for us? Teresa asked.

Hmm?

That bracelet?

Teresa smiled and drew her finger across the blue bracelet, tracing the bone of Dani’s wrist as she went. Despite the ocean’s chill, Dani felt the prickle of goosebumps. She could touch her own wrist a hundred times like that in the dark before sleep and never feel such a shiver

Dani! Becky’s voice sang above the hiss of the ocean. She began wading into the water.

Dani looked to her fingers which had somehow unworked the braid’s knot.

Here, Dani said, pushing the bracelet into the mush of Teresa’s fingers.

Oh my gosh, Teresa said.

That is so sweet, Bet added.

Are you sure?

I’ll just make another, Dani said, dismissing their affection. But they took no notice of her modesty or her smile or how she dove into the next passing breaker and rode it all the way to shore.

When she’d sleep, she’d dream of her mother, the different versions, the haircuts, the sweaters, but she’d also dream of Wolfy in that place. After reading the newspaper version, her mind couldn’t not. Wolfy now, her long mousy hair, seven years old, she looked somehow older and younger than that. Small and worried like a magic creature. Eyes dark like her own. Was it handcuffs? Was it a chain? Were there ropes like the kind that lifted ships’ sails? She studied for marks on the girl’s bony wrists. Was the basement finished? Was it a carpeted floor? What kind of things did he feed her? Bread and cheese, or food for a dog from a can? Wolfy didn’t cry when she’d cry. No tears. The mugshot of Cole Francis Diego. Matted hair, a mustache. He could’ve been anyone. It’s funny she never thought of her dad. And the story said there had been other girls down there too.

Before sunset, Dani pedaled her old green bike that she called Old Green. She loved it and loved for other people to see her on it. It was a 1963 Schwinn Fleet. Gabe had given it to her, and it truly was the prettiest bike in all LeFay, polished with turtle wax, spokes glinting silver, the wheels’ rubber wet black. Since she was on good behavior for the whole day and had no fights with Wolfy, Dani was allowed to go all the way to Jim & Jack’s where they had big bins of candy and other kinds of beach stuff.

At Jim & Jack’s Dani saw a kid she went to school with named Trip Fegley (whose real name was Albert, but he was Albert Fegley III, and so everyone called him Trip for Triple). He had blonde hair and blue eyes. Dani only had brown hair and brown eyes. When she saw him, she didn’t pretend like she didn’t know him. And he didn’t pretend either. He actually asked how her summer was going, and Dani said fine while acting really interested in the aisle’s junk (plastic sharks, orange hats, beer cozies). The tinny store speakers played a Cranberries song.

My dad said we can go out on my uncle Rick’s boat this week, Trip reported.

Are you going scuba diving?

No, just fishing maybe. My dad caught a marlin once.

Dani laughed and shifted her weight from one hip to the other.

Trip watched the way Dani’s gold legs ran all the way up her gym shorts. But even though she secretly wished he’d show her those blue eyes, he just stared down at her legs, and she stared at the stuff in the aisle.

Dani studied the shape Trip’s body made in her periphery. She smelled something spicy and clean. Was he wearing cologne?

Trip picked up a bucket hat with the word LEFAY stitched upon it in primary colors. He spun it around his finger until it fell onto the pile of other ladies’ bucket hats.

A marlin is basically a swordfish, Trip said.

Suddenly Dani took both Trip’s hands and did a little twist dance singing, Do you have to? Do you have to? Do you have to let it linger?

Trip laughed and pulled his hands away. They were sweaty.

What was that? he asked.

The Cranberries, Dani replied, pointing up to the invisible music. She held her breath. Her face burned. She turned away.

Oh yeah, Trip said. I heard them.

So what’s your favorite song? Dani asked as she stepped to the sunglass spinner.

Oh, Trip said. Well my dad really likes Jimmy Buffett. Cheese-burg-er in para-dise! He shout-sang.

No no, Dani regarded him via the mirror sticker on the display rack. Your favorite Cranberries song. She pushed a pair of dark oval frames onto her face.

Oh. I don’t know. That one I guess.

Linger, she said.

What?

Dani pushed her knuckles into her cheeks. The heat of her face had fogged the lenses. She smudged them with her fingertips, trying to wipe away the gray.

She sang softly to herself, ignoring the boy in the rearview.

Well, maybe I’ll see you, Trip said. Do you ever go to Bell Harbor?

Ok bye, Dani replied, doing a little wave and running to the candy bins.

Trip hesitated at first but was out the door and on the sidewalk by the time Dani realized she should have left first. Now no one would see her saddle Old Green and ride into the dusk.

At dinner Becky cooked spaghetti. After eating, Dani dumped out her brown bag of tootsie frooties from Jim & Jack’s and gave some of the blue ones to Wolfy because they were her favorite. Dani liked to do something nice even if Wolfy took a long time to pick the wrapper off with her shiny nails. It really drove Dani crazy that Wolfy couldn’t open it normally and had to pick it to death, but Becky was loving all the sisterly niceness, and she said, Just look at you two! And Dani thought, Yeah! Barfo!

Wolfy started cooing the chorus to Duran Duran’s “Ordinary World” through her sticky blue mouth while she picked at the next tootsie frootie wax paper.

Gabe joined from the sink as he scrubbed the burned sauce from the cheap rental property pot. But I won’t cry for yesterday, he sang in a soft tenor voice.

Is that really what she’s singing? Becky asked.

Dani started singing too, a big operatic rendition that made Wolfy squeal.

Alright alright, Becky said.

Dani realized her mistake and hoped to alter it by dumping the remainder of her tootsie frooties into Wolfy’s pile. Wolfy was not impressed and began smushing the candies with the flat of her palm.

Dani! Becky called.

What? Dani put her own hands up. Full surrender.

Stop her!

Dani lifted Wolfy’s hands from the sticky mess. Wolfy shrieked and scratched Dani’s wrist.

Ow you little Bee—!

Little what?

Little beech. Beach-Bum.

Uh-huh. You better watch that right now.

Dani put her middle finger under the table and pressed it so hard into the chair that it began to bend.

Why did you give her so many? Becky asked as she led Wolfy to the sink to wash her hands. That’s way too many.

Dani winced from the strain until she thought the finger would pop through the skin. Then she made a fist and felt the throb at the place where the bone had pressed.

I’m sorry, Dani said.

She wanted to wait longer to ask, but she couldn’t stand it anymore.

Can I ride my bike to Bell Harbor? she asked.

Bell Harbor? Becky looked up from wiping Wolfy’s hands with a paper towel. It’s a little far to bike by yourself. Dani felt an ache spread across her chest.

Bell Harbor was far—it was on the opposite end of the island—but other kids were allowed.

Gabe looked up from his balancing act at the dish rack, purple latex gloves covering his hairy arms. Bell Harbor is pretty far, Dani.

Dani began to burn a middle finger of fire from the center of her chest and push it all the way up, through the ceiling, into the sky, exploding it like the fireworks displays she used to see when they came for Fourth of July, before vacation got later and later.

You can go, Becky said. As long as you take Raylynn with you.

Gabe nearly dropped the coffee pot. He had a number of concerns. Besides the obvious problems of such a proposal, Gabe had wanted to work on flexion/extension exercises for Wolfy’s toe walking since Becky didn’t seem interested in doing it on the beach, even though it was a perfect environment for stuff like crab walks or other fun ways to increase her range of motion.

Dani didn’t need flexion/tension exercises or crab walks or bear walks or penguin waddles or frog jumps. She didn’t need floor ladder courses or bean bag lifts. She didn’t need to blow a cotton ball across the table with a drinking straw or push her lips together to practice plosives. She didn’t need hand signals to add additional stimuli when learning new sounds.

So why did she have to suffer?

From the car, Sea City sat on the horizon. A blob of light. A microscopic creature. Somewhere in the twinkle was the Ferris Wheel. Somewhere else, her mother maybe. Some night she’d come collect her after the boardwalk closed. She’d take her hand and flip a switch and the lights would pop back on. The rides would turn, the games would buzz, they’d take the train meant for the little kids. Stop at the Haunted Hollow, the Pirate Ship, the Spinning Saucer. And they could ride without lines, without any tickets. No height restrictions. Her mom was a carnival barker, a ring mistress, an amusement technician. She checked the seatbelts for the swings, swept up peanut shells, smoked behind the modesty fence at the lady’s restroom. She wore a tophat and lit swords on fire. She taught her which lipstick would match her pair of shades. She explained what exactly the tongue did during a French kiss. But even alone with such a mother in a wonderland dream, there, there, under the ramp to the arcade. A girl in an oversized T-shirt rattling her chain. The hole of her mouth, open, soundless.

They passed the dead part of the island between LeFay and Bell Harbor where it was all black with no houses. Just dune grass and pine trees. All four of them were in the car. Meaning: not only was Dani not allowed to pedal Old Green for all of Bell Harbor to see, but she still had the special mission of taking Wolfy out for a little frolic. Wolfy never listened to Dani, so what was she supposed to do if Wolfy decided to jump into a trashcan or climb a rain pipe? What was she supposed to do if someone tried to take her again?

When the streetlights came back, they were in Bell Harbor on a big main street like in Back to the Future. Wolfy looked at the people and scratched at the glass. Becky gave Dani a ten dollar bill and said they should go get ice cream, but only to the end of the block where the ice cream place was, and then they should come back. Gabe was squeezing the wheel and biting his lip, and when Dani looked at him, he smiled lousily and nodded his head. He didn’t say, We’ll be right here watching every single move you make. He did say, Be careful.

On the street where they parked, older kids were smoking smokes and sitting on the hoods of their cars while their girlfriends laughed at the T-shirts and knickknacks in different shops. The boys didn’t even look at Dani and her wolf sister. They just laid and leaned with their tight blue jeans and shorts the colors surfers wear. Light pink, sea green, neon red. Some of them even wore sunglasses in the night. Wolfy wouldn’t take Dani’s hand, but she did walk next to her. The smoking boys didn’t say anything, and Wolfy didn’t look at them, and Dani thought, Thanks be to you Oh God of Crazy Little Girls.

Other kids rode around on bikes, none of which were half as pretty as Old Green, but they were laughing loud, acting up, showing off. Dani tried to ignore them, but couldn’t help watching girls and boys her age palling around in little groups. The girls dropped their heads to look at the boys. They had legs like Dani, bendy and long and warm from the sun. Some of them had training bras, and some of them had real bras. The boys didn’t even have fuzz on their chicken legs, but the girls would’ve if they hadn’t started shaving with the pink disposable Bics their moms bought at the drug store. Becky got hers from Kmart. They followed each other around, into the Shore Shop, across the crosswalks, up on the benches outside Maldonetti’s Water Ice with little green lips and pink-purple tongues.

There was a line at the ice cream place. Dani considered whether to get an orange/vanilla swirl or a chocolate/vanilla swirl and how either way, there would be rainbow sprinkles on top, and when she looked in the direction of the car where Gabe and Becky still sat, she saw Trip Fegley and a pack of kids from home. Teresa Maxman was there with Bet Crowley, their belly buttons showing between matching white tank tops and short jean shorts.

Dani looked at Wolfy picking her lips, fingers making them pucker. Trip and Teresa and Bet and the others had a big bucket of popcorn, so they must’ve just seen something at the movies together, one big happy family, probably taking turns holding sweaty hands and French kissing and who knows what other kinds of diddling there in the dark. They were walking towards Dani. There was not enough time to try to drag Wolfy away, and besides, who knew what she’d do? Instead Dani looked at her, old Wolfy, and pretended like she was really happy about something she just said and hoped that maybe if she was normal and Wolfy was normal then the group wouldn’t even care.

But they did care. Trip saw her and said, Hey! real loud like he was actually excited to see her. So Teresa and Bet saw her too, and everyone stopped.

Dani looked up like she barely knew who any of them were and said, Oh hi.

Trip was all fired up from being in the group, so he shot off a bunch of questions: How’s it going? and, Why didn’t you tell me you were coming? and, Who’s this?

Who’s this? Who’s who? Dani looked at Wolfy like, Do you think this belongs to me?

And Wolfy, poor girl, she looked at Dani and pointed a finger at her face like, Of course I belong to you, you’re my sister and I’m your Wolfy. And now what was Dani supposed to do?

Oh this is just Raylynn.

Hi, Raylynn, Teresa said, holding out a hand to shake like some kind of pageant queen. I’m Teresa. And there on Teresa’s wrist, Dani’s blue braided bracelet dangled. Wolfy looked at it like, What?

Trip said hi too, but Wolfy kept looking at Dani’s bracelet on Teresa’s wrist. Then of course Teresa Fartface said, Um, can’t she hear?

And Dani said, Sure she can.

And Teresa Pigfart said, Are you sure?

And Bet Crowley with her bubblegum lip gloss laughed like a baby pig.

Dani wanted to walk away, back to the car, back to the house, under the bed, middle fingers torpedoing the whole crap island until it sank, sank, sank. But Trip was looking at her like he actually wanted to know, like his blue eyes would keep looking forever if she told him. So Dani asked Wolfy right to her face, Can’t you hear me? Thinking all you have to do is nod or laugh or do something other than stand there like a wet pup. But Wolfy just looked from Dani back to Teresa’s pink wrist. Bet laughed even more, so Dani asked Wolfy again, Can’t you hear? And louder, Hey! Bet was squealing, Dani was burning, she couldn’t even look at Trip anymore. Wolfy! She said loudly. Wolfy! she shouted. Then Bet shouted it and Teresa shouted it, Wolfy Wolfy Wolfy! Then Wolfy’s eyes started boiling and she let out a scream like a devil in the night. Big and sharp and terrible, it cut through all the fun the other people were having so they stopped and stared, and Trip Fegley who was holding the popcorn bucket jumped and popcorn shot out on the sidewalk.

Dani kept looking at Wolfy through that scream, she looked into her eyes into the very bottom of them past the part that was shining her back at herself. She felt how it rattled back there where the scream was coming from, down past the eyes, down into the throat of her, down past her ribs and her thighs and the bottoms of her little shoes, shoes Dani used to wear but with new laces Becky had strung on, down past the wet of the sidewalk and the cave of the street and the whole of the world.

After the car ride and the lecture, after the crying and the screaming and pressing middle fingers into the back of the carseat, Wolfy was carried to bed and rubbed with aloe and lullabied. Dani slipped out the sliding door and into the night. The grass at these shore houses was hard and sharp, not like the grasses of home. But Dani’s bare feet liked the bite, liked the pain. She imagined hopping on the grill with the rotten cover, leaping over the warped fence, skipping to shore, stealing a skiff, and meeting her mother on an island somewhere where she rented out bicycles and sold coconuts carved with pirate faces. Or in a city where she played the flute on a corner cemented with wet trash. Or by a river where she split logs and speared rainbow trout. Or in a cave with a fire in the winter. Where Dani could rake the coals, and Wolfy could wait there too, yes Wolfy too, without any ties, across the flame, at peace in that place. And mother, her hair in spiraling braids, would smile at them both, both girls, narrowing those dark eyes, looking from one to the other and back again.