The Flowers of Afterthought: Premises and Strategies for Revision

by David Jauss

February 3, 2020

I’ll begin this essay with an admission that I fear won’t surprise many of my readers: I have little or no talent for writing. Nothing (not even the simple sentence you just read) comes easily to me. Whenever I’ve taken part in timed writing exercises—which, for the record, I loathe—I produce a few clumsy sentences while virtually everyone around me writes pages of glittering prose. It would take me a week to write something half as good as what others can write in ten minutes. But although I lack natural writing talent, I do have a talent—or at least an aptitude—for rewriting, and I owe whatever small success I’ve had as a writer to it. I love what Bernard Malamud called “the flowers of afterthought,”[i] the discoveries, both large and small, that transform a barren patch of land into a garden. I revel in those afterthoughts, spending months and occasionally even years revising a story, poem, or essay before submitting it for publication. And speaking of stories, poems, and essays, my goal in this essay is to pass along practical strategies for revision that I and others have found useful in all of these genres, although most of my references will be to fiction. But before we turn to these strategies, I’d like to discuss ten premises that I believe should guide us as we practice the art of revision.

PREMISES

1. First Thought, Worst Thought

Beginning writers sometimes buy into Allen Ginsberg’s mantra “first thought, best thought”[ii] and assume that revision will only make their work worse. (Lucky for us, Ginsberg didn’t follow his own advice; as the facsimile edition of his various drafts of Howl reveals, that poem underwent numerous and extensive revisions.[iii]) Me, I’d argue that our first thought is the worst thought. If, for example, we write the words flat as a, our first thought will most likely be to write pancake next, but if we choose that word, we’re guilty of a cliché. The same principle applies to all other aspects of literature: if we don’t reject our first thoughts, we’ll end up with red-haired characters with fiery tempers; plots in which boy meets girl, boy loses girl, and boy gets girl again; rhymes like love / dove and June / moon; and potted themes like “love conquers all” and “crime doesn’t pay.” And just as our first thoughts tend to be our worst thoughts, so too our first drafts tend to be our worst drafts.

Hemingway once said “The first draft of anything is shit,”[iv] and I believe that’s true. But revision can turn that shit to gold. Many great works of literature were rewritten numerous times. I’ll give you a long list of examples later, but for now, let me just point out that Tolstoy wrote five separate drafts of Anna Karenina, each significantly different from each other.[v] As Edward Dahlberg said, “Books are not written; they are rewritten.”[vi] And if our first drafts seem shitty, we shouldn’t let that fact discourage us too much. As the songwriter Mike Smith has said, “When your work seems terrible, you should be grateful, because it proves you still have taste.”[vii]

2. Revision Is Play, Not Work

In Homo Ludens, his classic study of the play-element in culture, Johan Huizinga argues that play is at the heart of all human activity and therefore Homo ludens—ludens being Latin for playing—would be a more accurate name for our species than Homo sapiens. “All poetry is born of play,”[viii] he says, and I’d argue that the same is true of any mode of writing that is imaginative rather than expository or journalistic. The word play might suggest a lack of seriousness, but whereas “seriousness seeks to exclude play,” Huizinga says, play “include[s] seriousness.”[ix] Indeed, “serious play” is perhaps the best short definition of literature I can think of, akin to Frost’s definition of poetry as “play for mortal stakes.”[x] And while we associate play with childhood, play is not mere “child’s play.” Huizinga believes that play is the highest expression of the adult imagination, and I agree. So does a fellow named Nietzsche, who said that “A man’s maturity” consists of “having rediscovered the seriousness that he had as a child at play.”[xi]

Perhaps the characteristic of play that is most pertinent to writing is the disproportionate relationship between effort and return. If we approach writing as play, we are willing to put in the maximum amount of effort for a minimal amount of return; we’re willing to write dozens, maybe even hundreds, of pages to get a handful of keepers. But if we approach writing as work, our goal is to receive the maximum amount of return for the minimum amount of effort; we want every page we write to be a keeper. We often hear writers praised for their work ethic, but what writers really need is a play ethic. If we approach revision as work, we’re not in the right frame of mind to create anything of value. “Rewriting,” Robert Olen Butler maintains, “is redreaming.”[xii] No matter if we’re writing our second, third, or fiftieth draft, we should be employing the same playful, imaginative process we used to produce our first draft.

It’s important to note that approaching revision as play doesn’t mean it’s going to be nothing but fun. Like any form of play, frustration is an essential element of it. If there’s no impediment to serving an ace, hitting a home run, or writing a stellar sentence, there’s also no pleasure. And writing involves a nearly infinite number of impediments. Solving one problem often creates another—and when that problem is resolved, it, too, creates another. Anne Lamott was right to compare revision to putting an octopus to bed. “You get a bunch of the octopus’s arms neatly tucked under the covers,” she says, “but two arms are still flailing around.” And when “you finally get those arms under the sheets, too, and are about to turn off the lights,” that’s when “another long sucking arm breaks free.”[xiii] In revision, we need to expect, even welcome, many long sucking arms.

3. Revision Is Not a Separate Stage in the Writing Process

Edgar Allan Poe famously advised writers to imitate “the old Goths of Germany … who used to debate matters of importance to their State twice, once when drunk, and once when sober.”[xiv] The implication, of course, is that the writing process has two distinct and diametrically opposed stages, the first wildly enthusiastic, spontaneous, and creative and the second highly restrained, thoughtful, and critical. Hence many writers think they’re supposed to turn off their left brain while writing their first draft, then turn off their right brain while they revise it. They slop down a first draft, then try to salvage it with their intellect. As Catherine Brady notes, “Despite all the advice books that recommend settling for a sloppy first draft and trusting to revision, a practice of indifference toward” the quality of our writing in our first draft will inevitably lead to a sloppy revision. “One sentence leads to another,” she says, “and a bad sentence leads to another like itself.”[xv]

So we should write and revise both drunk and sober, alternating between left brain and right brain. As Jesse Lee Kercheval says, the rhythm of writing is “rather like marching: left brain, right brain, left brain, right brain. Your critical sense alternates with your creative sense.”[xvi] Thus, she adds, “it’s an artificial distinction to think of revision as a separate stage in the writing process. When I am writing a short story or chapter, I am revising all the time.”[xvii]

In short, revision takes place during all of the drafts we write, including the first. Many, if not all, of the strategies for revision I’ll discuss in this essay could be employed in the first draft as well as in any subsequent draft.

4. Revision Is a Collaboration Between Our Conscious and Unconscious Selves

Just as the revision process alternates between our left and right brains, it alternates between our conscious and unconscious selves. In an essay on the role the unconscious plays in creativity, Oliver Sacks recounts an experience the French mathematician Henri Poincaré had in 1880. For fifteen days Poincaré worked intensively on a complex mathematical problem, then his labors were interrupted by a lengthy trip, during which he forgot all about the problem—at least consciously. One day late in his trip, he stepped onto an omnibus and the solution to the problem popped into his head. This “sudden realization,” Poincaré wrote, was “a manifest sign of long, unconscious prior work.”[xviii] This and other similar incidents in Poincaré’s life convinced the great mathematician that, as Sacks says,

there must be active and intense unconscious activity even during the period when a problem is lost to conscious thought, and the mind is empty or distracted with other things. This is not the dynamic or “Freudian” unconscious, boiling with repressed fears and desires, nor the “cognitive” unconscious, which enables one to drive a car or to utter a grammatical sentence with no conscious idea of how one does it. It is instead the incubation of hugely complex problems performed by an entire hidden, creative self.[xix]

And this hidden, creative self is our wiser self. As Poincaré said, “The subliminal self … knows better how to divine than the conscious self, since it succeeds where that has failed. In a word, is not the subliminal self superior to the conscious self?”[xx]

As Poincaré’s experience suggests, an essential part of the creative process is to stop thinking consciously about the work so it can incubate in our unconscious. Hemingway certainly agreed; he advised writers not to think about their stories when they weren’t actually writing them. “That way your subconscious will work on it all the time,” he said. “But if you think about it consciously or worry about it you will kill it and your brain will be tired” when you return to your writing desk.[xxi] Not thinking about your story is not easy. As Andre Dubus said, it’s “as hard as writing, maybe harder; I spend most of my waking time doing it.”[xxii] We all want to solve our story’s problems, so it’s difficult to turn our conscious thoughts off and let our unconscious do its work. But if you do this, the solution will often pop into your mind, seemingly unbidden, at a later time. As Einstein said, “I think 99 times and find nothing. I stop thinking, swim in silence, and the truth comes to me.”[xxiii]

While we need to acknowledge the primacy of the unconscious self, we also need to remember the all-important role the conscious self plays in generating the unconscious work. As Poincaré stressed, the unconscious work “is possible, and of a certainty it is only fruitful, if it is on the one hand preceded and on the other hand followed by a period of conscious work.”[xxiv] Intense conscious labor forces problems into the unconscious, which then solves them days, weeks, months, or even years later. We aren’t always aware of the source of these solutions, or even of the fact that they are solutions—they don’t always arrive as “sudden realizations”—but if we put in the requisite conscious labor, we can trust the unconscious to supply what we need.

Peter Markus has said, “I always tell my students that the story is smarter than you, that it knows where it wants to go.”[xxv] But it’s not really the story that’s smarter than we are; it’s our unconscious self that is smarter than our conscious self, and we need to recognize the hints and clues it weaves into our drafts, to intuit what our deeper self wants us to write. The principal goal of revision, then, is to discover in what we have already written what we should have written.

5. Revision Is a Quest for Meaning

We tend to think of revision as primarily, if not solely, an aesthetic matter, something we do to improve the work’s literary value, and as a result we tend to read our drafts with an eye toward aesthetic enhancement. But revision is not merely a quest for aesthetic perfection; it’s also a quest for meaning. Tolstoy didn’t revise Anna Karenina repeatedly merely in order to polish its prose; as the substantial differences in plot and characterization in his five separate versions reveal, he was searching for his novel’s meaning.[xxvi] Robert Olen Butler sums it all up succinctly: “The point of revision is to find meaning.”[xxvii] Obviously, we can’t do this if we think we already know what our story means. Hence, as Jane Smiley says, “The first idea you need to give up when you begin to revise is that you know what this story is about.”[xxviii]

The main reason we don’t always, if ever, know what our story is truly about is that the writing process is a collaboration between our conscious and unconscious selves, and by definition we are unaware of our unconscious intentions. Given the role the unconscious plays in the creative process, it’s inevitable that our stories come out differently than we consciously intended. All too often we consider this difference a failure that needs to be corrected in revision, and so we struggle in draft after draft to make the story come out the way we initially intended when what really needs revision is our initial conception. If a story turns out differently than we intended, that’s a sign that our unconscious self wants to write a different story.

For me, then, the first step in revision is to try to see what the story is doing to subvert my conscious intentions for it. I look for details, characters, and scenes that in some way contradict or ignore my intentions. I consider them clues to the story that I, deep down, really want to write. The more we try to impose our initial conscious intentions on the story, the more we delay our discovery of what truly brought us to the material at hand—and thus our discovery of our work’s meaning. So my advice is to set aside, as much as possible, your conscious intentions when you look at what you’ve actually written. As T.S. Eliot says, between the idea and the reality falls the shadow,[xxix] and the shadow is where the story is.

In order to discover the story within the shadow, the real story underlying the original draft, we have to be open to discovering new meanings, especially meanings that contradict our original intentions, and to do that we sometimes have to write several additional drafts that may well be no better than the first one and might even be worse. We like to think of revision as a way of heightening the virtues and eliminating the vices of our initial draft—and that of course is our ultimate goal—but revision is often far messier than that: it’s a plunge back into the material, and it can roil up everything. It can be depressing and discombobulating as hell, but it can also be exhilarating, because it’s the only way we can find what’s at the hidden heart of our original effort. And finding that hidden heart, that previously unconscious meaning, should be the principal goal of revision, one more important even than aesthetic improvement. Saul Bellow said the revisions that made him happiest were not “stylistic” revisions but “revisions in my own understanding.”[xxx] And that kind of revision can only result from discovering your meaning.

6. You’re Not Just Revising Your Work, You’re Revising Yourself

As Bellow’s comment suggests, what we’re revising is not just a story and its characters; we’re also revising our opinions and beliefs—and therefore we’re revising ourselves. As the obsessive reviser William Butler Yeats said,

The friends that have it I do wrong

When ever I remake a song,

Should know what issue is at stake:

It is myself that I remake.[xxxi]

George Saunders echoes this point when he says that revision makes him “better than I am in ‘real life’—funnier, kinder, less full of crap, more empathetic, with a clearer sense of virtue, both wiser and more entertaining.”[xxxii] However “laborious” and “obsessive” revision may be, he adds, it becomes “addictive” when you discover that it can create “a better version of yourself.”[xxxiii] And creating a better version of ourselves just may be the single most important reason to revise.

7. Don’t Trust Your Brother, Trust Your Own Bad Eye

While it’s always wise to consider the advice your teachers, workshop classmates, and friends offer you, there’s nothing more deadly to the creative process than following someone else’s suggestions for revision as if they were instructions. As I see it, my job as a teacher is to tell my students as honestly and clearly as possible what I think they should do to improve a story, and their job is to sift through that advice and decide what, if anything, will help them achieve their vision. In his Nobel Lecture, Alexander Solzhenitsyn urged writers to follow the advice of the Russian proverb “Don’t trust your brother, trust your own bad eye.”[xxxiv] Your teachers, classmates, and friends may have your best interests at heart, and you may be all too painfully aware that you don’t see your work clearly enough, but ultimately all we have as writers is our instinct about what is right for our story and what isn’t.

This is not to say that we’ll always be right, of course. As Janet Burroway has said, sometimes the advice “you resist the hardest may be exactly what you need.”[xxxv] But I’d argue that you should follow your instincts nonetheless. If someone’s advice feels right, adopt it. If it doesn’t, don’t. You may eventually realize your instincts were wrong, but if you assume from the start that they are and robotically follow the advice you receive, your chances of becoming a better writer are greatly diminished. Bum Phillips, the former coach of the Houston Oilers and the New Orleans Saints, once said there were two kinds of football players who weren’t “worth a damn”—the kind who never does anything he’s told and the kind who does everything he’s told.[xxxvi] Be sure you don’t become either kind of writer.

8. A Work Is Never Finished

Paul Valéry once said, “A work is never … finished, for he who made it is never complete.” W.H. Auden translated this comment as “A poem is never finished; it is only abandoned,”[xxxvii] but Valéry actually said nothing about abandoning a work. Rather, he stressed the almost infinite possibility for revising and improving it. He said that “the power and agility [the writer] has drawn from [writing the work] confer on him … the power to improve it” and that each draft he writes teaches him how to “remake it”[xxxviii] yet again. A writer might abandon a work, true, but if so, it’s not because the work can no longer be improved. Ultimately, Valéry argues that both a work and its author are works in progress, and neither are ever truly “complete.” And if that’s the case—and I believe it is—we should feel free to revise our work throughout our life.

Some writers disagree. They argue that the revision process should end when a work is published, not when we stop breathing. Richard Hugo disparaged writers who revise old work, calling them “time effacers” because revision inevitably distorts who they were and what they felt and thought at a certain time in their lives.[xxxix] And likewise, Mark Doty says he doesn’t revise any of his published poems because “There’s a certain degree of respect you have to give to the person you were then, to the fact that you made a shape out of experience and language that stood for something about that hour in your life.”[xl] Me, I don’t think the purpose of a work of literature is to be a snapshot of who I was at a given time. All I’m concerned about is the quality and meaning of the work itself. I’m with good old “spontaneous” Whitman, who revised the poems in Leaves of Grass throughout his life, producing nine vastly different versions of the book in the thirty-seven years between its first publication and his death, and I’m also with Proust, James, and Yeats, all of whom likewise revised their work after it was published. I feel a responsibility toward the work I’ve written, and toward the people who may one day read it, and so I want to make my work as good as I can. And if that means returning to it years after it was published and revising it significantly, well, I’m more than willing to do that. Since time plans to efface me, I don’t feel the least bit guilty about effacing as much of it as I can.

9. Revision Can Be (Too) Seductive

While revision is, as Malamud said, “one of the exquisite pleasures of writing,”[xli] and while a given work can be revised and improved virtually infinitely, it’s important to keep in mind that revision can seduce us away from generating new work. As Will Allison has said, “For me, revision is the most satisfying aspect of writing and the most seductive form of procrastination.”[xlii] We need to make sure we’re continuing to revise for the right reasons, not merely to avoid the difficult task of launching into the blank page and writing something new.

10. You Can’t Step into the Same Revision Twice

Eudora Welty once said, “Every story teaches me how to write it, but not the one afterward.”[xliii] Similarly, each story teaches us how to revise it, but not how to revise the next story. As George Saunders has said, “It feels like every story has … its own necessary revision process.”[xliv] As we turn to a survey of fourteen revision strategies, please keep in mind that the revision process will of necessity be somewhat different for each story.

STRATEGIES

I. PREPARATION

1. Defamiliarize Your Draft

The more familiar we are with the words on the page, the harder it is to recognize how they should be changed. So the first step of any revision should be to defamiliarize your draft. The ideal way to do this is to let a significant amount of time pass before you look at it again. This not only gives your unconscious self the time it needs to work on the problems your conscious self has overlooked, it allows you to read the work more like a reader than an author. Andre Dubus III recommends that we wait “at least six months” before reading our draft. “Have two seasons go between you,” he says. “And then when you pick it up and read it, you actually forget some of what happens in the story. You forget how hard it was to write those twelve pages. And you become tougher on it. You see closer to what the reader is going to see.”[xlv]

But what if you’re a student and have a story due in two weeks, not six months? How can you defamiliarize your draft in that little time? I suggest you print it out in a different font, preferably one you think is ugly. And if that doesn’t do the trick, I suggest you also try printing it on different-colored paper or with different-colored ink.

Another approach is to tape record your story. Most people hate to hear their tape-recorded voice, so if you listen to a tape of yourself reading the story, you’re almost certain to hear things you’ll want to change.

And one other possibility: do the equivalent of putting your iPod on Shuffle: read and revise paragraphs or scenes of your story in random order. If you intentionally eliminate the story’s narrative arc, you can focus more intently on its parts, and what would otherwise be all too familiar just might seem unfamiliar, even new.

2. Look for Clues to Your Story’s Meaning

Once we’ve defamiliarized our draft, we’ll be better able to discover its meaning. As I said earlier, the first thing I do when I revise is look for details, characters, and scenes that in some way subvert or ignore my conscious intentions. I consider them clues to the story my unconscious self wants me to write, as opposed to the one my conscious self intended.

In my early years as a writer, I automatically cut anything that didn’t seem to fit my intentions. Then something Eudora Welty said made me realize that was a mistake. She said, “It’s strange how in revision you find some little unconsidered thing which is so essential that you not only keep it in but give it preeminence when you revise.”[xlvi] Her comment led me to interrogate each seemingly “unconsidered” or inessential aspect of a draft, trying to discover if it were a clue to something essential about the story. We may not have a conscious reason for including a certain detail, but we often have an unconscious one, and a major part of the revision process is discovering what led us to include details that don’t seem to serve any clear purpose. I suggest you not cut these extraneous-seeming details, at least not until you’ve fully explored their possible significance. Those “little unconsidered things” are our unconscious self’s way of telling us to consider something, and sometimes it’s the detail that seems most extraneous that holds the story’s deepest and most important secret. Our drafts are like treasure maps, and the “little unconsidered things” are often clues to the location of the buried treasure.

II. EXPANSION

The process of discovering our story and its meaning continues throughout every draft we write, but once we’ve scoured our initial draft for clues to what the story is truly about and have a fairly clear understanding of our story’s meaning, we can begin revising in earnest. The temptation is to go through our story line by line, deleting this, adding that, and changing the wording here and there, and while this approach almost invariably leads to an improved draft, the result is not a true revision; it’s just a premature editing job. “Revise” means to “re-see,” and to re-see our story we have to do more than just edit what we’ve already written; we have to imagine what we haven’t yet written.

Revising a story is a bit like playing an accordion: just as you have to expand and contract the bellows of an accordion to make music, you have to alternate between expansion and contraction in order to create a story. Most talk about revision focuses on contraction, but unless you begin the revision process by expanding your story, you may not discover what you need to contract. As Lee Martin has said, “I find that the first revisions I make often center on an opening up of aspects of the piece that are under-developed or not developed at all. … I keep asking myself what the piece hasn’t yet said. I keep poking at the character relationships and the plot to see what might surprise me.”[xlvii] Only after he feels he’s discovered what’s missing does he start to think about what he can leave out. We’ll look at ways to compress shortly, but for now, here’s some advice for expanding.

3. Revise Blind

In my experience, the single most helpful strategy for revision is to revise blind—that is, without looking at your previous draft. As Peter Selgin has said, “Old words can block fresh insights,”[xlviii] so if your story isn’t working, I suggest you rewrite it—or at least the problematic parts of it—without looking at your old words. Try to forget what you already wrote and reimagine it. After you’ve finished, compare the original and the revision to see what you’ve lost and gained (usually it’s not all one or the other) and mix and match the two versions to create a new version. Don’t do this just once; do it as many times as necessary until the story feels right to you.

If you need any further encouragement to try this approach, consider the fact that D.H. Lawrence wrote Lady Chatterley’s Lover three times, each time beginning from scratch and without “referring to the existent versions.”[xlix] If this approach is good enough for Lawrence, I think it ought to be good enough for the rest of us.

4. Write Outside the Story

Another way to discover how to expand and deepen a given scene without looking at what you’ve already written is to write “outside the story” awhile—in other words, write something that you don’t intend to use in the story but that might help you better understand your characters and plot. Elizabeth Libbey recommends writing outside the story as a way “to return to working inside it,” and she suggests various ways of doing this, including “exploring the inner life of your main character through diary entries, letters, dreams, or lists” and writing “a scene that occurred before the beginning of the story” or after it ends. Referring to Hemingway’s famous theory of omission, she says, “Even if you don’t use this material in the story, it will, as Hemingway said, make itself felt.”[l]

Often, a scene I’ve written won’t work because the protagonist is the only character in it that I even somewhat know, so I’ll rewrite the scene from the point of view of one or more of the other characters in the scene. I do this not because I intend to change the story’s point of view (though I keep that possibility open) but because I want to get to know the characters well enough to make the scene work. Once I have a better idea of what they’d say, do, and think, I can generally go back to the original scene and make it stronger.

5. Slow Down Where It Hurts

All too often, we skip over, speed through, or summarize our stories’ most dramatic moments. We do this partly out of a legitimate fear of melodrama but mostly, I suspect, out of a desire to avoid depicting our characters’ emotional pain. In life, avoiding conflict and pain is usually a virtue, but in fiction, it’s always a vice. Fiction thrives on the torqueing up of tension, not the avoidance of it. So, as Steve Almond wisely says, we should “Slow down where it hurts”[li] and allow not only our characters but our readers and ourselves to experience the pain. The moments that hurt the most are the moments that most deserve expansion.

6. Write Vertically

In his essay “The Habit of Writing,” Andre Dubus talks about writing “horizontally” for his first twenty-five years as a writer, trying to get from point A to point Z in a draft as quickly as possible, then going back to revise it five or six times. His goal during those years was to write five pages per day, but one day while working on his story “Anna,” he began writing “vertically,” trying, as he said, “to move down, as deeply as I could” into whatever moment he was writing about and capture all of his character’s thoughts and physical sensations. Instead of five pages a day, he wrote just one or two, but slowing down allowed him to discover his story faster and finish it in fewer drafts.[lii] If there’s a moment in our draft that feels underdeveloped or unexplored, we should follow Dubus’s lead and try to write it “vertically” instead of horizontally. In short, sometimes we need to slow down even where it doesn’t hurt. And sometimes by slowing down we discover a hurt we’ve overlooked.

7. Take Out the Highlighters

As Flannery O’Connor once said, a scene doesn’t come to life unless it evokes at least three of the five senses. “If you’re deprived of any of them, you’re in a bad way,” she said, “but if you’re deprived of more than two at once, you almost aren’t present.”[liii] To make sure your readers will be present in your scenes, go through your story and highlight each of the five senses with a different color, and if you find a scene evokes fewer than three senses, add more sensory details.

Also, writers tend to belong to one of two camps—the eye-oriented or the ear-oriented—and both camps tend to over-rely on two of the four principal modes of narration and under-rely on the other two. Eye-oriented writers over-rely on action and description, and ear-oriented writers over-rely on dialogue and thought. In life we are all pretty much continually talking, thinking, acting, and perceiving the world around us, so fiction that weaves these four modes together with relative balance tends to best replicate life as we experience it. To achieve this balance, eye-oriented writers often need to expand their scenes by adding dialogue and thought, and ear-oriented writers often need to expand theirs by adding action and description. I suggest you go through your scenes and highlight each of the four modes with different colors, so you can see which modes you overuse and which you underuse.

8. Employ Oppositional Thinking

Expansion is not only literal; we don’t just need to expand our scenes, we also need to expand our characters, make them as round and life-like as possible, and I think oppositional thinking is the key to doing this. As Janet Burroway says, to create three-dimensional characters we need to put at least one of the four modes of narration into opposition with the others.[liv] A character who talks, thinks, acts, and looks confident is a one-dimensional stereotype, but if he talks, acts, and looks confident but thinks insecure thoughts, he instantly becomes more complex. And if we put a single mode of narration into opposition with itself—if the character believes in God one moment and another moment is racked with doubt—he becomes even more complex. The more contradictions a character contains, the more complex and compelling he becomes.

Oppositional thinking can also help us expand the significance of our plots. When you revise a story, ask yourself at every significant moment of the plot “If the character did, said, or thought the opposite thing here, how would the rest of the story change?” If you write a “counter-version” of a key moment of your story, you can often find a larger and more compelling story than the one you originally intended. Jonathan Raban reports that Robert Lowell followed this strategy often: “His favorite method of revision,” he says, “was simply to introduce a negative into a line, which absolutely reversed its meaning but very often would improve it.”[lv]

So if you decide you took a wrong turn at some point in the story, I suggest you try reversing whatever happened at that point, then try to discover what would happen next. I’ve done this in many of my stories, and rightly or wrongly, I think it’s improved them. And I’m a rank amateur when it comes to oppositional thinking. I’ve changed old characters to young ones, and vice versa, and turned weddings into funerals, but other writers have taken oppositional thinking a lot farther in their revision process. Tobias Wolff, for example, has even changed the sex of several of his characters.[lvi]

9. Fine-Tune Your Soundtrack

I wholeheartedly second Stuart Dybek’s advice that we “try for the impossible: to make the piece of writing itself have its own interior soundtrack, one that a reader who listens might almost detect.”[lvii] We should be creating this soundtrack during our initial draft too, of course, but in the early stages of the process we are often distracted by matters of characterization and plot and so don’t give the music of our prose the full attention it deserves. In revision we can, and should, take the time to expand and fine-tune our story’s soundtrack.

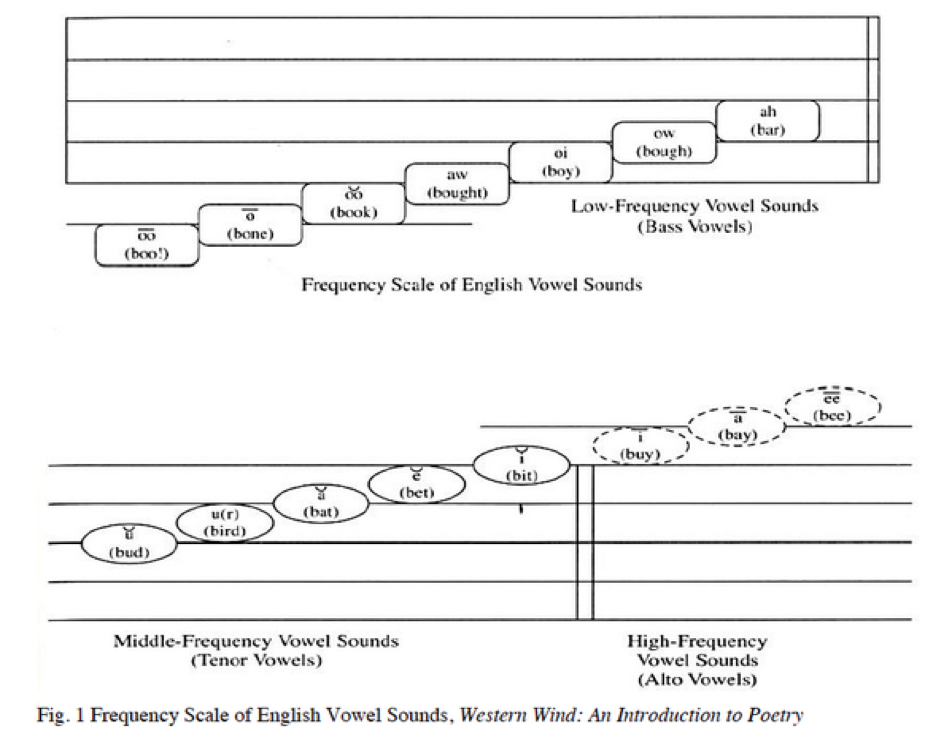

We should ask ourselves if the sounds we’ve chosen—the consonants and vowels of our words—are appropriate for the mood we want to create. If we’re after a calm, serene mood, a preponderance of hard, plosive consonants like b, d, g, k, and t will work against that mood. If we want to put the reader on the edge of his seat with terror, we should avoid using relatively soft, soothing consonants like l, m, n, and w. According to the poet John Frederick Nims, vowel sounds are even more important than consonants for creating our soundtrack. He thought vowels were so inherently musical that he created the following “vowel scale,” arranging the vowels on a musical staff according to the frequency of their sounds.[lviii]

If we want to convey a happy, excited, intense, agitated, or fearful mood, we should use, wherever possible, words with “alto” vowels—words like cry, yea, and eek. Conversely, if we want to convey a somber, dejected, or depressed mood, we should use words with “bass” vowels—words like gloom, moan, lost, and frown.

If you don’t believe Mr. Nims or me, maybe you’ll believe Keith Richards. Here’s what Keef says on this subject:

[Mick and I] also composed using what we called vowel movement—very important for songwriters. … Many times you don’t know what the word [you’re looking for] is, but you know the word has got to contain this vowel, this sound. … There’s a place to go ooh and there’s a place to go daah. And if you get it wrong, it sounds like crap. It’s not necessarily that it rhymes with anything at the moment, and you’ve got to look for that rhyming word too, but you know there’s a particular vowel involved.[lix]

We also need to pay close attention to the rhythms created by the placement of stressed and unstressed syllables in our sentences and, even more, the rhythms created by the variations in our syntax. Syntax and music are very closely related—and I mean that literally. As Ellen Bryant Voigt has pointed out, neurolinguists have discovered that the brain’s “syntax centers” are “adjacent to where we process music.”[lx] Pascal said, “Words differently arranged have different meanings, and meanings differently arranged produce different effects”[lxi]—and to a large extent those effects are musical. But all too often we over-rely on one pet sentence structure and that compromises the rhythm of our soundtrack. If we overuse short simple sentences, for example, we create an overly choppy, staccato rhythm, and if we overuse long, periodic sentences, we can create a sense of stasis, of treading linguistic water, that hinders the story’s narrative momentum. One way to find out if you’re relying too much on certain sentence structures is to take out your highlighters again and highlight your simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences with different colors. I also suggest highlighting left-, mid-, and right-branching sentences to see which ones you overuse. And once you’ve identified problematic sentences and passages, you can combine or divide sentences to create rhythms that are both more various and appropriate to your story’s soundtrack.

Just as we need to pay attention to the rhythms of our sentences, we also have to pay attention to the tempo of our scenes and chapters. Milan Kundera says that parts of his novels “could carry a musical indication: moderato, presto, adagio, and so on.” He describes Part Five of Life Is Elsewhere as having “a slow, tranquil … moderato” pace, and Part Four as having “a feeling of great speed: prestissimo.”[lxii] Tempo is a complex thing with many variables, but it is largely defined by the relation between the length of a given passage and the amount of “real time” it covers. When Proust recounts a three-hour-long party in a leisurely 190 pages of In Search of Lost Time, the tempo is lento to the nth power, and when he dispatches an entire decade in one whiplash-inducing sentence, it is as prestissimo as prestissimo can get.[lxiii] So look at the relationship between the length of your scenes and the “real” time they cover, and if the tempo seems too slow or too fast to create the feeling you’re after, adjust the tempo accordingly.

III. CONTRACTION

To go back to my accordion analogy, once we’ve expanded the bellows, we need to compress them to make music. As Lee Martin has said, “Experience has taught me that sooner or later during the additive part of the [revision] process, something will click, and I’ll know the piece more fully than I did when I first began writing it. It’s that click that then gives me permission to start subtracting, cutting anything that doesn’t belong, anything that slackens the pace, anything that bloats the narrative, anything that makes the language vague and loose.”[lxiv]

As we’ll discuss later, writers tend to write hundreds, even thousands, of pages in the process of producing their work. They do so, Anthony Doerr points out, because “It takes time to learn how much you can get away with not saying.”[lxv] In order to discover our characters and plots and their meanings, we always have to write a lot more than the reader needs to read, and a major part of revision is deciding what the reader needs to know as opposed to what we needed to write. But once we’ve discovered what Martin calls “the heart of the piece,”[lxvi] we can begin to cut anything that that is superfluous to conveying that heart.

10. Revise as if You’ll be Charged by the Word, Not Paid by It

It’s almost impossible to read an interview with an author that doesn’t include the admonition to cut, cut, cut. Truman Capote said, “I believe more in the scissors than I do in the pencil”[lxvii]; Vladimir Nabokov said, “My pencils outlast their erasers”[lxviii]; Peter De Vries said, “When I see a paragraph shrinking under my eyes like a strip of bacon in a skillet, I know I’m on the right track”[lxix]; and Isaac Bashevis Singer said, “The wastepaper basket is a writer’s best friend.”[lxx] And authors regularly tell us what to cut, too. Chief on the hit list are adjectives and adverbs. “The adjective is the enemy of the noun and the adverb is the enemy of the verb,” Voltaire purportedly said,[lxxi] and Chekhov, Twain, and numerous other writers have likewise urged us to cut adjectives and adverbs. But of course none of these writers recommended we cut all of them. Twain famously said, “If you catch an adjective, kill it,” but he not-so-famously added, “No, I don’t mean utterly, but kill most of them—then the rest will be valuable. They weaken when they are close together. They give strength when they are far apart.”[lxxii]

And there’s one other thing that everyone agrees we must cut: our best writing. Virtually everybody who’s ever commented on revision has quoted Arthur Quiller-Couch’s famous injunction “Murder your darlings” (and virtually everybody has also falsely attributed this quote to a more famous author).[lxxiii]But of course you shouldn’t murder all of your darlings any more than you should kill every adjective.

In any case, there’s a way to murder our darlings that allows them to be resurrected to serve another story. Benjamin Percy says he keeps what he calls a “Cemetery folder.” “In it,” he says,

I have files—tombstones, I call them—with titles like “Images” or “Metaphors” or “Characters” or “Dialogue.” Into these I dump and bury anything excised from a story. For some reason, having a cemetery makes it easier to cut, to kill. Perhaps it’s because I know the writing isn’t lost—it has a place—and I can always return to the freshly shoveled grave and perform a voodoo ceremony.[lxxiv]

So sometimes a writer’s best friend is a cemetery folder, not a wastepaper basket.

11. Purge Your Superfluities

Michelangelo, who knew a thing or two about beauty, defined it as “the purgation of superfluities.”[lxxv] He clearly believed that less is more. Some writers, however, think more is, well, more, and they’d rather give us the entire iceberg, not just the one-eighth of it that Hemingway recommends. In the debate about whether writers should be putter-inners or taker-outers, I cast my vote for Fitzgerald, who preferred taker-outers, not Thomas Wolfe, who defended his putter-inner instincts in a famous letter to Fitzgerald.[lxxvi] There are of course many great writers who were putter-inners—Wolfe mentions Cervantes, Sterne, Dickens, and Dostoevsky and we could easily add many others to the list—but I believe their works would be even greater if they’d purged more of their superfluities. Mark Twain, despite being a bit of a putter-inner himself at times, would have taken Fitzgerald’s side in this argument. As evidence, I offer his wryly ironic one-sentence critique of the everything-but-the-kitchen-samovar approach that Tolstoy takes in War and Peace. “Tolstoy,” he complained, “carelessly neglects to include a boat race.”[lxxvii] I hope all of you will carelessly neglect to include not only boat races but anything else equally superfluous.

12. Play a Cutting Game

To achieve a leaner draft, Janet Burroway recommends we “play a cutting game” and shorten our draft by some arbitrary amount.[lxxviii] Sarah Stone and Ron Nyren are a little more specific; they say “Imagine that the editor of your favorite magazine has called up and said, ‘I’ll take it, if you can make it 20 percent shorter.’ See if you can meet this challenge without harming the story.”[lxxix] I’d go one step further: play this game more than once.

13. Downsize Your Cast of Characters

Stone and Nyren also advocate downsizing your cast. “Examine the characters in your story, major and minor,” they advise, and “consider the story without each one.” Obviously, if two characters are performing the same function, one is expendable. And if one character’s actions or dialogue could “be appropriately assigned to another character,” you could give the first character a pink slip. And if you have “two underdeveloped characters,” they suggest combining them to “form a [single] complex character.”[lxxx]

Jesse Lee Kercheval also has a valuable suggestion: “Count lines to see if the space the characters take up is proportional to their importance in the story.”[lxxxi] I’ve found in my own initial drafts that some of my minor characters take up almost as much space as my protagonist, and that fact led me not only to recognize the story’s lack of proportion but also my failure to explore the central character as fully as I should.

14. Start Later and End Earlier

Chekhov said, “Once a story has been written, one has to cross out the beginning and the end.”[lxxxii] All too often beginnings are little more than throat-clearings. We hem and haw for a few pages, then the story truly starts. As Kurt Vonnegut advises, we should “throw away the first six pages … all the reader really wants is for the story to get started as soon as possible.”[lxxxiii] Chekhov goes even further; he says, “Rip out the first half of your story; you’ll only have to change the beginning of the second half a little bit and the story will be totally comprehensible.”[lxxxiv]

And whereas openings tend to be unnecessary throat-clearings, endings tend to be unnecessary explanations or clarifications. The real ending of a story, the ending that implies all that follows it, often occurs a paragraph or a page or even several pages earlier. A good ending reverberates with what is unsaid, unexplained, but nonetheless deeply conveyed.

IV. RINSE AND REPEAT

Revision is best understood as a singular term for a plural process. After we finish a revision, we need to begin the process again by once more defamiliarizing our text in order to continue discovering our meaning and to judge more accurately what needs further expansion and contraction. As I’ve already mentioned, Tolstoy wrote five separate versions of Anna Karenina and D.H. Lawrence wrote three separate versions of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. (All three versions of Lawrence’s novel have been published, in case you’d like to compare them for insight into his revision process.[lxxxv]) Here are some other examples of writers who felt the need to “rinse and repeat” numerous times.

Frank O’Connor said, “Most of my stories have been rewritten a dozen times, a few of them fifty times.”[lxxxvi]

Leo Tolstoy spent a year writing fifteen drafts of the opening thirty-page scene of War and Peace.[lxxxvii]

Ernest Hemingway rewrote the first part of A Farewell to Arms “at least fifty times”[lxxxviii] and wrote thirty-nine drafts of its final page.[lxxxix]

Dan Chaon typically writes more than a hundred pages in order to produce a fifteen-page story.[xc]

Andre Dubus spent fourteen months writing his story “Waiting.” It was more than one hundred pages in early manuscript form, but when it was published in The Paris Review, it was only seven pages long.[xci]

Isaac Babel wrote twenty-two separate versions of his story “Lyubka the Cossack.” All told, he wrote over two hundred pages to create a six-page story.[xcii]

Gabriel García Márquez once used up five hundred sheets of paper in the process of writing a fifteen-page story.[xciii]

James Thurber wrote fifteen complete drafts of his story “The Train on Track Six,” composing a total of 240,000 words in the process of creating what was eventually a 20,000-word story.[xciv]

Charles Johnson wrote more than 3,000 pages in the process of writing his 210-page National Book Award-winning novel Middle Passage.[xcv]

Gustave Flaubert wrote 4,561 pages in the process of writing his 400-page novel Madame Bovary.[xcvi]

Tolstoy wrote over 7,000 pages in the process of writing his 450-page novel Resurrection.[xcvii]

One caveat to the “rinse and repeat” mantra: As Toni Morrison has said, “I’ve revised six times, seven times, thirteen times. But there’s a line between revision and fretting, just working it to death. It is important to know when you are fretting it; when you are fretting it because it is not working, it needs to be scrapped.”[xcviii]

If you’re truly revising, not fretting, you should wait until you feel you can’t improve the work further—at least at this stage of your writing life—before you submit it for publication. In his Ars Poetica, Horace advises waiting nine years before publishing, just to make sure your draft is truly the final one,[xcix] but I doubt too many of us would be willing to take his advice. Me, I think if all you’ve been doing for weeks is taking out a comma in the morning and putting it back in the afternoon, I think your work’s ready to go out into the world, hat in hand, and knock on editors’ doors.

CONCLUSION

I hope some of the premises and strategies I’ve discussed help you improve your work. But my main advice is to cultivate perseverance. As the Japanese proverb says, “Fall seven times, stand up eight.”[c] And I also urge you to keep in mind what Will Shetterly has said is the greatest thing about revision: “It’s your opportunity to fake being brilliant.”[ci]

NOTES

[i] Bernard Malamud, Interview by Daniel Stern, Writers at Work: The Paris Review Interviews, Sixth Series, ed. George Plimpton (New York: Viking, 1984), 167.

[ii] Ginsberg credited the motto “First thought, best thought” at various times to William Blake, Jack Kerouac, Ghögyam Trungpa, and others.

[iii] Allen Ginsberg, Howl: Original Draft Facsimile, Transcript, and Variant Versions, ed. Barry Miles (New York: HarperCollins, 2006).

[iv] Ernest Hemingway, quoted in Arnold Samuelson, With Hemingway: A Year in Key West and Cuba (New York: Random House, 1984), 11.

[v] C. J. G. Turner, A Karenina Companion (Wilfrid Laurier U Press, 1993), 13.

[vi] Edward Dahlberg, The Carnal Myth: A Search into Classical Sensuality (New York: Weybright & Talley, 1968), 11.

[vii] Mike Smith, quoted in XXX, “As It Turns Out, George Saunders Loves Revision Too,” UCWBling, Feb. 4, 2013. http://ucwbling.chicagolandwritingcenters.org/george-saunders-writing-advice/

[viii] Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture (Mansfield Centre, CT: Martino Publishing, 2014; reprint of New York: Roy Publishers edition of 1950), 129.

[ix] Ibid., 45.

[x] Robert Frost, “Two Tramps in Mud Time,” The Poetry of Robert Frost, ed. Edward Connery Lathem (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1969), 277.

[xi] Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future, tr. Marion Faber, Oxford U Press, 1999, 94.

[xii] Robert Olen Butler, From Where You Dream: The Process of Writing Fiction, ed. by Janet Burroway (New York: Grove Press, 2005), 38.

[xiii] Anne Lamott, Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life (New York: Anchor Books, 1995), 93-94.

[xiv] Edgar Allan Poe, “Letter to B—–,” Selections from the Critical Writings of Edgar Allan Poe, ed. Frederick C. Prescott (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1909), 1-10 and 323-325.

[xv] Catherine Brady, Story Logic and the Craft of Fiction (New York: Palgrave/Macmillan, 2010), 169.

[xvi] Jesse Lee Kercheval, Building Fiction: How to Develop Plot and Structure (Madison: U of Wisconsin Press, 2003), 131.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Henri Poincaré, “Mathematical Creation” (excerpt from his autobiography), tr. by George Bruce Halsted, in The Creative Process: A Symposium, ed. Brewster Ghiselin (New York: New American Library, 1952), 38.

[xix] Oliver Sacks, “The Creative Self,” The River of Consciousness (New York: Knopf, 2017), 144.

[xx] Poincaré, 39.

[xxi] Ernest Hemingway, By-Line: Selected Articles and Dispatches of Four Decades, ed. William White (New York: Scribner, 1998),216.

[xxii] Andre Dubus, “The Habit of Writing,” in On Writing Short Stories, ed. Tom Bailey (New York: Oxford U Press, 2000), 90.

[xxiii] Alfred Einstein, https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/842695-i-think-99-times-and-find-nothing-i-stop-thinking

[xxiv] Poincaré, 38.

[xxv] Peter Markus, “How to End,” https://www.writingclasses.com/toolbox/articles/how-to-end

[xxvi] C. J. G. Turner, A Karenina Companion, 13.

[xxvii] Butler, 58.

[xxviii] Jane Smiley, “What Stories Teach Their Writers: The Purpose and Practice of Revision,” in Creating Fiction: Instruction and Insights from Teachers of the Associated Writing Programs, ed. Julie Checkoway (Cincinnati, OH: Story Press, 1999), 248.

[xxix] T.S. Eliot, “The Hollow Men,” The Complete Poems and Plays, 1909-1950 (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1971), 58.

[xxx] Saul Bellow, quoted in Maggie Simmons, “Free to Feel: Conversation with Saul Below, Quest, Feb. 1979, 31-35; reprinted in Conversations with Saul Bellow, ed. Gloria Cronin and Ben Siegel (Oxford: U Press of Mississippi, 1994), 165.

[xxxi] William Butler Yeats, Untitled poem, Yeats’s Poems, ed. A. Norman Jeffares (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1998), 713.

[xxxii] George Saunders, https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/8885.George_Saunders?page=9

[xxxiii] George Saunders, quoted in Adam Vitcavage, “George Saunders Likes a Challenge,” Electric Literature, Feb. 14, 2017. https://electricliterature.com/george-saunders-likes-a-challenge-bb92c31fc8b40

[xxxiv] Russian proverb, quoted in Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Nobel Lecture, tr. by F.D. Reeve (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1972).

[xxxv] Janet Burroway, Imaginative Writing: The Elements of Craft (New York: Longman, 2003), 228.

[xxxvi] Bum Phillips, https://www.sbnation.com/nfl/2013/10/19/4855684/bum-phillips-quotes

[xxxvii] W. H. Auden, Collected Poems, ed. Edward Mendelson (New York: Vintage, 1991), xxvi.

[xxxviii] Paul Valéry, “A Poet’s Notebook,” in The Poet’s Work: 29 Poets on the Origins and Practice of Their Art, ed. Reginald Gibbons (U of Chicago Press, 1989), 173-74.

[xxxix] Richard Hugo, from a conversation with the author in the fall of 1980.

[xl] Mark Doty, quoted in Jona Colson, “Mark Doty: An Interview,” The Writer’s Chronicle, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Sept. 2011), 20.

[xli] Malamud, 167.

[xlii] Will Allison, “Throw Up, Then Clean Up,” Rules of Thumb: 73 Authors Reveal Their Fiction Writing Fixations, ed. Michael Martone and Susan Neville (Cincinnati, OH: Writer’s Digest Books, 2006), 234.

[xliii] Eudora Welty, quoted in “A Conversation with Susan Neville,” Story Matters: Contemporary Short Story Writers Share the Creative Process, ed. Margaret-Love Denman and Barbara Shoup (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006), 358.

[xliv] George Saunders, source unknown but Saunders confirmed the authenticity of the quotation in a Sept. 3, 2019, email.

[xlv] Andre Dubus III, “The Case for Writing a Story Before Knowing How It Ends,” by Joe Fowler, theatlantic.com/entertainment/print/2013/10/the-case-for-writing-a-story-before-knowing-how-it-ends/280387/

[xlvi] Eudora Welty, Conversations with Eudora Welty, edited by Peggy Whitman Prenshaw (New York: Washington Square Books, 1984), 346.

[xlvii] Lee Martin, “The Addition and Subtraction of Revision,” https://leemartinauthor.com/2018/01/29/addition-subtraction-revision/

[xlviii] Peter Selgin, “Revision: Real Writers Revise,” in Gotham Writers’ Workshop, Writing Fiction: The Practical Guide from New York’s Acclaimed Creative Writing School, ed. Alexander Steele (New York: Bloomsbury, 2003), 218.

[xlix] Ibid.

[l] Elizabeth Libbey, “Writing Outside the Story,” What If? Writing Exercises for Fiction Writers, ed. Anne Bernays and Pamela Painter (New York: HarperPerennial, 1991), 164.

[li] Steve Almond, This Won’t Take But a Minute, Honey: Essays (Boston: Harvard Bookstore, 1995), 17.

[lii] Dubus, 92-93.

[liii] Flannery O’Connor, “The Nature and Aim of Fiction,” Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose, ed. Sally and Robert Fitzgerald (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1981), 69.

[liv] Janet Burroway, Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft, 5th ed. (New York: Longman, 2000), 139.

[lv] Jonathan Raban, quoted in Ian Hamilton, Robert Lowell (New York: Vintage, 1983), 431.

[lvi] Tobias Wolff, “A Conversation with Tobias Wolff,” in Margaret-Love Denman and Barbara Shoup, Story Matters: Contemporary Short Story Writers Share the Creative Process (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006), 476.

[lvii] Stuart Dybek, interview with Jennifer Levasseu and Kevin Rabalais in Glimmer Train Stories, Issue 44 (Fall 2002), 88-89.

[lviii] David Mason and John Frederick Nims, Western Wind: An Introduction to Poetry, 5th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005), 154-155.

[lix] Keith Richards, Life (New York: Back Bay Books, 2011), 267.

[lx] Ellen Bryant Voigt, The Art of Syntax (St. Paul, MN: Graywolf Press, 2009), 8.

[lxi] Blaise Pascal, Pensées, ed. and tr. Roger Ariew (Cambridge, MA:Hackett Publishing Co., 2005), 192.

[lxii] Milan Kundera, The Art of the Novel (New York: HarperPerennial, 2000), 88.

[lxiii] Gérard Genette, “Time and Narrative in A la recherché du temps perdu,” in Essentials of the Theory of Fiction, ed, Michael J. Hoffmann and Patrick D. Murphy (Durham, NC: Duke U Press, 1988), 284.

[lxiv] Martin, “The Addition and Subtraction of Revision.”

[lxv] Anthony Doerr, “Manufacturing Dreams: An Interview with Anthony Doerr” by Richard Farrell, Numéro Cinq, Vol. III, No. 1 (Jan. 2012), http://numerocinqmagazine.com/2012/01/13/manufacturing-dreams-an-interview-with-anthony-doerr/

[lxvi] Martin, “The Addition and Subtraction of Revision.”

[lxvii] Truman Capote, Conversations with Capote, ed. Lawrence Grobel (New York: New American Library, 1986), 205.

[lxviii] Vladimir Nabokov, Strong Opinions (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1973), 4.

[lxix] Peter De Vries, quoted in Leonore Fleischer, “De Vries on Rewriting,” Life (Dec. 13, 1968), 18.

[lxx] Isaac Bashevis Singer, quoted in Morton A. Reichek, “‘Yiddish,’ says Isaac Bashevis Singer, ‘contains vitamins other languages don’t have,” New York Times (March 23, 1975), 228,

[lxxi] Voltaire, quoted in Thomas Kennedy, Realism and Other Illusions: Essays on the Craft of Fiction (Portland:Wordcraft of Oregon, 2002), 122.

[lxxii] Mark Twain, March 20, 1880, letter to D.W. Bowser, in Mark Twain’s Notebooks: Journals, Letters, Observations, Wit, Wisdom, and Doodles, ed. Carlo De Vito (New York: Black Dog & Leventhal, 2015), 58.

[lxxiii] Arthur Quiller-Couch, On the Art of Writing (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2006; reprint of 1916 edition), 203.

[lxxiv] Benjamin Percy, “Home Improvement: Revision as Renovation,” in Thrill Me: Essays on Fiction (St. Paul, MN: Graywolf Press, 2016), 165-166.

[lxxv] Michelangelo, quoted in Wordsworth Dictionary of Quotations, ed. Connie Robertson (Ware, Hertfordshire, UK: Wordsworth Editions, 1998), 275.

[lxxvi] Thomas Wolfe, July 26, 1937, letter to F. Scott Fitzgerald, in The Sons of Maxwell Perkins: Letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Wolfe, and Their Editor, ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli and Judith S. Baughman (U of South Carolina Press, 2004), 258.

[lxxvii] Mark Twain, quoted by Richard Bausch in an interview in Glimmer Train Stories (Spring 2000), 129.

[lxxviii] Burroway, Imaginative Writing, 225.

[lxxix] Sarah Stone and Ron Nyren, Deepening Fiction: A Practical Guide for Intermediate and Advanced Writers (New York: Pearson/Longman, 2005), 214.

[lxxx] Ibid.

[lxxxi] Kercheval, 136.

[lxxxii] Anton Chekhov, quoted in Valerie Miner, “Revising Revision,” Rules of Thumb: 73 Authors Reveal Their Fiction Writing Fixations, ed. Michael Martone and Susan Neville (Cincinnati, OH: Writer’s Digest Books, 2006), 132.

[lxxxiii] Kurt Vonnegut, “How to Get a Job Like Mine,” quoted in Tina Zambetis, “Author Vonnegut tells fans how to get a job like his at speech,” Daily Kent Stater, Vol. 56, No. 109 (April 19, 1983), 9.

[lxxxiv] Anton Chekhov, quoted in A.B. Derman, “Compositional Elements in Chekhov’s Poetics,” in Anton Chekhov’s Short Stories, ed. Ralph E. Matlaw (New York: Norton, 1979), 302.

[lxxxv] D.H. Lawrence, Lady Chatterley’s Lover (New York: Penguin Classics, 2010) and The First and Second Lady Chatterley Novels, ed. Dieter Mehl and Christa Jansohn (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge U Press, 1999).

[lxxxvi] Frank O’Connor, The Lonely Voice: A Study of the Short Story (Brooklyn, NY: Melville House Publishing, 2004), 211.

[lxxxvii] Jeff Wells, “18 Novel Facts about War and Peace,” Mental Floss, Sept. 9, 2018 https://mentalfloss.com/article/85834/18-novel-facts-about-war-and-peace

[lxxxviii] Ernest Hemingway, quoted in Arnold Samuelson, With Hemingway: A Year in Key West and Cuba (New York: Random House, 1984), 11.

[lxxxix] Ernest Hemingway, “The Art of Fiction No. 21,” interviewed by George Plimpton, The Paris Review, No. 18 (Spring 1958).

[xc] Benjamin Percy, “Home Improvement: Revision as Renovation,” in Thrill Me: Essays on Fiction (St. Paul, MN: Graywolf Press, 2016), 165.

[xci] Joshua Bodwell, “The Art of Reading Andre Dubus,” Poets & Writers (July/August 2008), 22.

[xcii] Ruth Almog, “The Right Words, the Last Words,” Haaretz, Oct. 18, 2002, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/the-right-words-the-last-words-1.31065

[xciii] Gabriel García Márquez, quoted in Marlise Simons, “Love and Age: A Talk with García Márquez,” The New York Times Review of Books, April 7, 1985.

[xciv] James Thurber, The Paris Review Interviews, II, ed. Philip Gourevitch (New York: Picador, 2007), 22.

[xcv] John Williams, “‘Middle Passage’ at 25,” New York Times, July 10, 2015.

[xcvi] Brigid Grauman, “Madame Bovary goes interactive,” Prospect Magazine, May 2009. http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/madamebovarygoesinteractive

[xcvii] Korneliĭ Zelinskiĭ, Soviet Literature (Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1978), 185.

[xcviii] Toni Morrison, The Paris Review Interviews, II, ed. Philip Gourevitch (New York: Picador, 2007), 361.

[xcix] Horace, Ars Poetica, lines 389-391, tr. by A.S. Kline, https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Latin/HoraceArsPoetica.php

[c] Japanese proverb, quoted in The Poet’s Notebook: Excerpts from the Notebooks of 26 American Poets, ed. Stephen Kuusisto, Deborah Tall, David Weiss (New York: Norton, 1997), 26.

[ci] Will Shetterly, http://www.azquotes.com/author/38377-Will_Shetterly

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

David Jauss is the author of four collections of short stories, including Glossolalia: New & Selected Stories and Nice People: New & Selected Stories II, two volumes of poetry, and the essay collection Alone With All That Could Happen (reprinted in paperback as On Writing Fiction). His stories have won the AWP Award for Short Fiction and National Endowment for the Arts and Michener Fellowships and they have been reprinted in the Best American Short Stories, O. Henry Award, and Pushcart Prize anthologies. He teaches fiction writing at Vermont College of Fine Arts and is completing a new collection of essays on the craft of fiction titled The World Inside the World.