An Interview with Leah Silvieus

Hope Fischbach

April 5, 2022

Could you tell us about the relationship between dirt and grief that echoes through your book, specifically in the poem “Water Street Elegy” (“O Potomac O dirty O constant / reviser. How sky forgets, scours even / our eulogies back to water, back / to muck, to dirt”) and in the repeated phrase “dirt-road orphans”?

Dirt operates on a few different levels in this collection. The places where I grew up and where many of these poems draw from geographically was…well, dirt-y, in the sense that my surroundings were full of mud and dust and soil. I spent a lot of time as a kid in the dirt: building dirt forts, planting and harvesting vegetables from my family’s garden, driving down dirt roads, searching for shiny stones in our dirt driveways. So in that way, dirt—and the mountains and rivers and forests that cut through and sprang from it—was connected to, and shaped everything. There is also the connection between grief and dirt in burial, but dirt is also that which provides the nutrients and space for rebirth.

“Maryland Route 210, Dusk” and “Self-Portrait as Secret-Heart-of-Gold Boy” speak from opposite angles of the human need to see and be seen. The emotions of repulsion, guilt, and dread saturate “Maryland,” as the speaker passes by a (presumed) dead body, believing that she, too, will be passed over unseen and unrecognized. In “Self-Portrait,” the speaker burns with envy, anger, and desire, realizing that while she sees, she may never be truly seen: “I mistook this recognition for love.” Yet the poems themselves do the important work of seeing. Would you talk about how you recognize the overlooked and marginalized?

That is a beautiful observation but not something that I really noticed before. I think that on some level, the attention to the vulnerable in these poems is a way of examining my own vulnerability and the ways in which I long to be seen and recognized and even I dare say, loved. I think, at least for me, examining my own desires for connection and recognition can feel incredibly exposing and painful. I think that sometimes I find it’s easier for me to trust a poem with those feelings than another person or even myself. Sometimes I find that it’s a way of tricking myself into looking at those feelings, of creating a framework to explore these feelings that might be too painful for looking at up close. I am also interested in looking at the ways in which vulnerability works to shape our relationships and the world around us by determining what we feel compassion for, what we find threatening, what we identify with, and what we otherize.

Throughout Arabilis, specifically in poems like “Invasive Species,” “Maryland Route 210, Dusk,” “Water Street Elegy,” and “Matthew 19:14,” you contrast the mercilessness of the world with the mercy we find in ourselves. You also contrast intention with outcome, such as in “Matthew 19:14”: “stole change from Right to Life / coin banks to buy Ring Pops for our little sisters,” and in “Invasive Species”: “his leg now askew / from where I had broken it in my hurry / …I was just trying to help.” How does the work of poetry redeem these experiences of good intentions resulting in complicated outcomes? How does poetry both reveal and inspire mercy in a world that is often cruel?

This is such a great question. I am not sure that poetry (or anything, maybe) does redeem experiences of good intentions resulting in complicated outcomes, but I think it can provide a space to sit with those complicated ethical situations, to consider the relationships between cruelty and mercy, to feel our way through them, to borrow from the critical theorist Sara Ahmed. Poetry helps me to look, and look closer, at those things that make me uncomfortable, especially within myself, with regard to things like cruelty and mercy. And being able to sit with those moments in which my speaker is cruel or unmerciful, I think, prompts me to think about the ways in which I have been cruel or unmerciful and how I tell the stories about those moments and to whom and to what end.

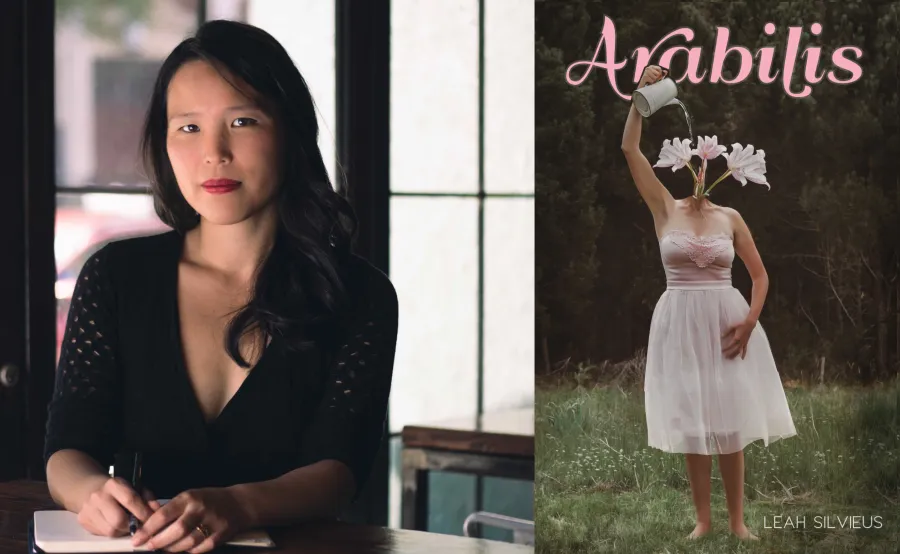

The cover of this book is so striking. How was it decided on?

When I was thinking of images for the cover, I wanted a surreal image that included the feminine and the natural world. I was scrolling through Instagram one night and I found this image on the website of South African artist Cheeky Ingelosi, and I knew instantly that it was the one. Then the wonderful team at Sundress Publications came up with the rest of the design.

Threading through the whole book is an undeniable spirituality, especially in “Invocation” and “Benediction.” What led you to open and close with these poem-prayers?

Recently, thinking liturgically has helped me organize my creative work. I first began to see it in my first chapbook, Anemochory (Hyacinth Girl Press), and it continued with my second chapbook, Season of Dares (Bull City Press). “Invocation” is a cento comprised of lines from other poems in the collection. I looked at it as a means of tying the collection together as well as providing a way for the voices in the poems to speak together across space and time – and in a sense, to invoke each other. I wrote “Benediction” rather early in the process of this collection, thinking about questions such as, “After we arrive at the place that we’ve longed for, what happens then?” “What lasts?” “How do we continue to make ourselves new?” This book feels very much like a point of departure for me rather than an arrival, and I wanted to end of the book to give some sense of that.

An obvious question, but one I feel should be asked, is about the book’s seasonal sections. The book seems to chart a death of the past self and everything the speaker has known, ending with the regrowth of Spring. Where did this idea come from?

I didn’t construct the book around the seasons but, as I was gathering all of the poems together and considering how they would sit with each other and converse within the collection, the seasons seemed to be a natural organizational theme. Plus I think that many of the spaces/places that have shaped me as a person have a connection to the seasons whether it’s the seasons of the year or of the church calendar or of my personal development. I really love the circularity of the seasons as well; on one level, we are progressing forward but also we also are always returning to the place we began.

The seasons sometimes are referenced in more than one section. For example, in the Winter section, autumn is mentioned in the poem “The World Just Now, Emerging.” Could you say more about this?

Specifically in “The World Just Now, Emerging,” the autumn burn pile is something that builds up over the fall – fall leaves, dead vegetation from the garden, old wood from home projects, etc. – and is burned in the winter once the threat of spreading fire has passed. But on, I guess, a more emotional or spiritual plane, while the seasons to me in some ways seem discrete periods that mark the rhythms of the year, they are intimately tied. We often see the residues or fingerprints of one season in another: we gather the dead stuff during fall and burn it in winter, the snowfall in winter plays a part in determining of the intensity of fire season in summer, for example. I think seasons of life can work that way too: each season owes some part of itself to what preceded it; each season leaves traces on what follows.

“Field Dressing” and “Field Elegy” seem to work hand-in-hand but discuss different emotions. In “Field Elegy,” the speaker lets go of what the boys taught her (killing, skinning, and cleaning the deer) and instead mourns the dead fawn. Is she growing and stepping into her own? Or is she shifting away from easy childhood acceptance of family tradition?

These questions reflect such wonderful and insightful readings of these poems! I feel like so often others’ readings make revelations and connections that I wasn’t aware of myself—and help me read my own work more deeply. Those two poems were written about two years apart and until I read this question, I didn’t actually realize how they speak to each other. The reading your question reflects is so incisive, and I think that it might be both/and. Growth entails both shifting away from inherited traditions while also becoming aware of how those traditions have shaped oneself as a person. Even as someone tries to escape cycles of violence, the aftermath, even the habit, perhaps, of that violence still remains. There is a tenderness in the way the speaker holds the heart and yet she still throws it to the dogs— is that another gesture of violence that is related to the boys’ violence? Is it an act of mercy to the dogs? I don’t know, but this question makes me want to think about this more.

The speaker seems to start with a settled faith early in the book and later struggles with the beliefs she once relied upon. What do you hope the reader takes away from this journey?

I don’t think I have anything specific in mind except to say that while this book isn’t precisely autobiographical, writing the poems in this book have been a means of refracting/re-envisioning/complicating/conversing with both my conflicts and connections with my inherited faith tradition. A lot of those tensions are still not worked out and so I can’t say that there’s something that I hope that readers take away except that it’s okay to feel tension with/struggle with/rage against one’s beliefs, one’s faith tradition, one’s past. There might not be a unified narrative that explains or connects or make sense of everything, but that’s okay and I hope that my poems remain alive to those tensions.

With thanks to Dr. Will Woolfitt.