Elephants Bury Their Dead

Jasmine Sawers

Radchana lists between the refrigerator and the pantry. Her choices are between a crusty cheese rind and expired spaghetti sauce. There is no bread or pasta. On the floor of the pantry is a mouse trap with the tender pink curl of a tail trailing out. In the fridge there is the balm of the cold. She closes the pantry, she opens the fridge. She closes the fridge, she opens the pantry. And so on. Radchana doesn’t have to call her mother to hear it: Why you stand with door open? You want ahaan to go bad? There’s kids in Thailand with no ahaan!

Radchana leans into the chill. She presses her face into the freezer, her shriveled fruit peel belly into the shelves. She sets one foot on the lowest shelf, poised to clamber inside, when her phone rings. She puts it on speaker and sets it on the floor beside her.

“How are you holding up, Rachel?” asks Amber from HR.

Shit’s fucked, Amelia, she thinks.

“As well as can be expected, thanks for asking,” Radchana says.

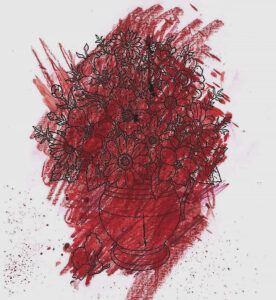

“Did you get the flowers we sent?”

Lilies, left to molder on the front porch. The smell of lilies makes Radchana sick on her best day. Her best days are behind her.

“Yes, we loved them,” she says.

“Listen,” Amber says. Noisy static rumbles down the line—a sigh. “I know we said to take as much time as you need…”

Radchana kneels before the refrigerator and lays her head on an empty shelf. It’s sticky, wiped carelessly and long ago of its maple syrup residue, its coconut milk, its curries and yogurts and juices. Radchana closes her eyes. The fridge smells stale, like freezer-burned ice cream. The crisper drawer bites into the deflated flaps of her breasts. She pushes in harder.

“Rachel.”

“I’m here,” Radchana says.

“I know it’s a bad time, but I need to ask how much longer you think you’ll be.”

Radchana sits up and shuts the fridge door.

“What’s a good timeline for you?” she says. “Three to five business days?”

“God, I know,” Amber says. “I’m sorry. It’s just, your maternity leave was up last Friday. I need a general ETA by the end of the week.”

“I have to go get groceries,” Radchana says.

“Rachel. You should be resting.”

“That circus is setting up on the fairgrounds,” Radchana says. “The traffic will be too bad to go anywhere by the time it opens.”

“How about I send Laura to help you?” Amber says. “She’d be happy to, you know that.”

The trunk of an elephant inches into the periphery of Radchana’s vision as if groping for a snack.

“I gotta go,” she says. She hangs up as Amber chants a name that’s not hers.

Sam is sobbing in the nursery again. Barefoot, Radchana leans in the doorjamb and watches as he shudders and hitches over the bassinet, curled into himself like a child being kicked in the schoolyard. The mobile, a cabal of origami elephants sent by happy aunts back in Thailand, rotates slowly as if the force of Sam’s gasping set it back into motion.

The floor creaks beneath her and Sam stiffens, plugs up his weeping. He unfurls his body like a flower and raises his hand to present a soft cotton elephant—Cameron’s favorite, lost these two weeks.

“I found it under all those onesies in his closet,” Sam says, voice like a cracked mirror. He doesn’t turn around, but ducks his head and scrubs his face with his shirt. A gift from Radchana’s brother, Somchai, they had been calling it Chang, Sam mangling the tone on purpose, just to make Radchana laugh. He tucks it back into the bowl of his ribcage and squeezes his whole body around it. His forehead brushes the rim of the bassinet.

“What should we do?” Radchana says, and into the sniffling silence she clarifies: “About the chang?”

They have these awful keepsakes now. A plaster cast of Cameron’s hands and feet, barely bigger than a fifty-cent piece bearing Kennedy’s face. A little pair of Converse he had never gotten to wear, bronzed. An urn the size of a Yankee candle, waiting to be filled. Radchana supposes Chang will join them all on the shrine Cameron’s changing table has become. She wants to knock it all to the floor with a sweep of her arm like an angry man on television.

“I just need another minute,” Sam says.

It’s never a minute. It’s hours and hours, as if there aren’t groceries to buy and showers to take. As if it isn’t Radchana’s turn to gaze, uncomprehending, into the empty bassinet.

“Do you need anything at the grocery store?” Radchana says.

Sam shakes his head. Silver twines now through the near-black of it like creeping ivy. When she first met him, she wondered if he were Asian—half, perhaps, or a quarter. That black hair. The almond chip eyes with a glint of green. The kind of skin that gets called “olive.” She was hooked by the time she got the full accounting of his heritage—he was Greek, he was Russian, he was Irish and French and all manner of other flavors that meant he was the kind of American who passed all his days without being interrogated about his right to be here.

They had hired someone to paint a mural in the nursery: a myriad of fresh greens, blues and browns, round baby animals hiding in the leaves. A jungle. The closest they could get to Radchana’s true home—that place she spent summers with her grandparents in an open air house raised high above the ground, a fan at her bedside, puffing inward the canopy of mosquito netting. Cicadas and birds, a distant adhan at dawn. She’d wanted something of that lush, untouched world for Cameron, but all she’d been able to offer was paint. A fantasy rendered worse than silly.

“I’ll be home in an hour,” Radchana says.

American grocery stores have jackfruit now. She’s always tempted when she sees one, but she never buys. What would she do with an entire jackfruit? She’d never get the tack off. She’d eat until she vomited. She’d eat until it came spurting out of her, joot joot.

They have mangoes as well, the big Mexican kind in a kaleidoscope of red and green. Lychees, too—never in good shape. Sometimes ngô—she always has to work to remember the English word and its inelegant, stumbling pronunciation: rambutan.

She is wrist-deep in the hairy vines of the ngô when she hears the last thing she wants to hear right now.

“Rachel!”

Radchana grabs a bunch of ngô without inspecting them and chucks them into her cart. She strikes a swift pace through the produce with her chin tucked into her chest.

“Rachel! Rachel!”

Laura from work arrives at her side, red-faced and huffing as if she’d performed a great feat running all the way from the deli counter, and clasps a heavy hand on Radchana’s shoulder.

“Rachel! God,” she says. “You shouldn’t be out.”

Not today, Laura, Radchana thinks. A year ago. A month ago. Two weeks and three fucking days ago, and I’d take it. But not today.

“My name is Radchana,” she says.

Laura drops her hand. Radchana fixes her gaze on the strawberries. She hears her mother’s voice in her head, her mother’s half-and-half pronunciation. Staw-ber-ly. Boo-ber-ly. Back-ber-ly.

“Oh, right,” Laura says. “Greg said it would be easier.”

“Radchana isn’t hard to say,” Radchana says.

“It’s just that in English, we want to emphasize the ‘cha’ part.”

“So don’t,” Radchana says. Instead of I’m from here, instead of I have two degrees in English.

“I’ll do my best,” Laura says.

Radchana pushes her cart forward. It’s peach season. Peash. Pum. Her mother never says the word ‘nectarine.’ Peash no skin, she says.

Laura is trailing desperately behind her.

“Listen,” she says, and Radchana sighs as if her lungs are a pair of sooty fireplace bellows. She stops and plays at inspecting the avocados. A-bo! ca-do!

“Ratch,” Laura says, and that’s somehow worse: half a tool, half synonymous for trashy, busted, which Radchana is, of course: greasy, stained, unwashed and uncombed in public. Laura sounds how everyone sounds when they’re gearing up to say something about your dead baby: like she’s getting a cold on top of her constipation. “Why don’t you give me your grocery list and I’ll handle this for you? It’s the least I can do.”

At least it isn’t, “God wanted him more than you.” “God called an angel home.” “When God closes a door, He opens a window.”

At least it isn’t, “Did you put a blanket in his crib?” “Did you lay him on his stomach?” “Did you take him to see someone who smoked?”

At least it isn’t, “What have you done to deserve this?” “You’re being punished.” “Fast and make merit.”

“Don’t worry about it, Laura,” Radchana says. “I just needed to get out of the house, you know?”

Laura’s hand hovers near her shoulder as if to make another rough landing, but she drops it back to her side instead. A lump of tension, of humidity, springs up between them. God, Radchana thinks. I hope she doesn’t cry on me.

“I get that,” Laura says. A baby elephant peeks out from behind her.

Radchana closes her eyes. Laura’s hand returns and rubs her back. Radchana cringes away.

“Sorry,” Laura says, yanking back as if burnt. “Sorry!”

Radchana rounds the corner of another fruit display and leaves Laura to recede into the background. None of the apples Radchana or Sam like are available. A-peun, comes her mother’s voice, calling her back.

By the time she was twelve, Radchana was an old hand at her yearly trip back to her grandparents and no longer required escort. In Thailand, everyone looked like her and no one ever stopped to grill her about her origins. In Thailand, Radchana had cousins and neighbor kids to play with and chickens to chase and dogs and cats to befriend despite Khun Yai’s shrill admonishments. She had pocket money for all the Pocky and Hello Panda she could eat. The little deprivations—English, school friends, Saturday morning cartoons—were as good as dust to her once she set foot in Thailand.

Her parents drove her across the border into Canada to drop her off at the Toronto airport, laden with an extra piece of luggage overfilled with gifts for her grandparents, her great aunts and uncles, her regular aunts and uncles, her cousins and second cousins and other cousins of indeterminate removal. Fourteen hours to Tokyo and another three or four to Bangkok, where a great aunt picked her up, mouth black with maak. At any given auntie’s house, she was stuffed full of pa thong ko and sankaya before she was bundled onto an overnight train to Lampang. To her grandparents, stooped and smiling at the train station, waiting to pick her up.

“Oh ho,” they said. “Nong Na is getting so big I can’t pick her up anymore.”

Paved city roads gave way to lumpy rural ones along which Khun Ta had to inch and lurch, muttering apologies to his truck’s suspension. Khun Yai in the front seat chattering the hours away.

“How is Khun Mae? How is Khun Pau? How is Pi Somchai? Aunt Ma and Aunt Da are making your favorites: kai palo, gai yang, nua waan. Aroy mai?”

“Aroy dee,” Radchana said.

An hour or two outside Lampang and there were no more city lights. Dirt paths and banana leaves, jungle cover. Houses on stilts. Men squatting in groups, throwing dice, smoking hand-rolled cigarettes. Children running, laughing, shrieking. The smell of food cooking throughout the neighborhood, pungent and fragrant. And sometimes, when everyone was asleep and there was only the sound of the breeze and the cicadas whistling down the trees in tandem, Radchana could hear them: the wild elephants.

In the car, Radchana calls her brother.

“Hey, Na.” Somchai is harried, probably ducked into a closet at work. He was allowed three days of bereavement leave. Radchana and Sam had held off on a funeral so he could combine his leave with a weekend and have enough time to drive here and back.

“Sorry, you’re at work,” Radchana says. “I can call back later.”

“Mai phen rai,” he says. “Anything you need,” he says. “Just say the word,” he says.

It has always been thus, since they were children. Since he was a child and she an infant. He a teenager and she a gawky lump just entering puberty. He off to college and she taking his place as the grandchild sent abroad each summer, out of their parents’ hair. Somchai, taking care of her.

There is ice cream in the backseat that will melt if she doesn’t get a move on. She wrenches the lever of the driver’s seat and drops backward. She closes her eyes against the sag of the fabric on her car ceiling. She listens to her brother breathe until he says he has to go, he loves her, call anytime.

Laura interrupts her silence with a tap to her window and Radchana screams. Laura raises her hands in surrender, her face a rictus of mortification, and she steps back. Radchana can see her saying, sorry, sorry.

Radchana pulls the lever again and jackknifes up. She turns the car on so she can press the button to roll the window down.

“What, Laura,” she says.

“Do you want me to call someone for you?” Laura says. “Is Sam home?”

“He’s busy,” Radchana says.

“Okay,” Laura says. “How about your mom?”

Radchana stares at Laura, whose face is doing an impression of a piece of paper being balled up. Radchana presses the button to slide the window back up. Laura is butchering her name, over and over. Rat-chin-a, like a rat, like the delicate, feminine na is but an afterthought to be swallowed.

Radchana drops her seat again and turns the radio up loud enough to drown Laura out. An old Kinks song segues abruptly into an ad for the circus.

“This weekend only! Fun for the whole family! Don’t miss the camel and elephant rides!”

One night, Radchana woke to the sound of trumpeting. Mournful calls back and forth, the trees shaking around the sound of it. She pushed aside her moongand crept out the side door and down the steps. She found some flip flops and followed the trumpeting into the thick of the jungle. She walked and walked, the air grown cool with the hour, her arms and legs a puffy map of mosquito bites. She was parched by the time she came to a clearing, where a knot of elephants stood, trunks raised high as they called out. There were more than ten of them—several adult females and a series of their offspring from infancy to adolescence.

One of the babies, perhaps only days or even hours old, had fallen into a muddy hole. It may once have been a fire pit, but now it was a yawning reservoir as narrow as it was deep, a sharp reminder of the gathering monsoon. The mother knelt before the hole, swiping back and forth at the baby with her trunk, keening all the while. Other elephants took turns trying to lift the baby from the hole by their trunks, but they were thwarted by the slip of the mud. Though the baby squealed its distress, Radchana could see only its trunk flailing above the hole. She could see only the slosh of brown water over the edge of the pit.

Radchana had been taught to revere elephants for their intelligence, their empathy, and their peaceful natures. So, too, had she been taught a healthy caution.

“You are not a farang,” her aunt told her, years ago on her first summer in Thailand. “Don’t go thinking an elephant is your pet like some kind of dog.” Aunt blew through her teeth and swept her arm out like a trunk, like a slap. “One wrong move and pang! Khun Chang will kill you.”

Radchana knew better than to approach. These females and juveniles may not go into musth, but in this moment of high stress, Radchana knew she could not help. She was barely a hundred pounds, and the baby was at least twice her size. She would not be able to pull it up. She would not be able to get into the hole and push it out, either. If the mother were so inclined, Radchana may not even survive the attempt. She could do nothing but watch from behind the thickness of the palm trees, even as her tongue swelled for water, even as her feet and thighs ached for reprieve.

She watched the baby and its mother struggle for hours as the herd trumpeted around them. Useless tears trailed down her face. The night deepened and grew cool enough to make Radchana shiver until even the darkness broke and the sky began to lighten. Before dawn spilled over the canopy, birds woke to trill out their songs.

As the heat of the day seeped back into Radchana’s skin, the baby stopped crying, stopped fighting to get out of the hole. Its trunk went limp. Its mother cried out and swept her trunk over its head, its little body. The rest of the elephants, shifting in place, called out mournful notes even as their trunks reached without purchase toward the sky. They brushed the mother with their trunks and then fanned out. Radchana scrambled backwards when one came near her, the big groping trunk barely missing her spot in the brush. Radchana thought the great beast looked right into her eyes, right into the core of her where she was stricken and alone, but the trunk curled around the big palm frond above her and snapped it away from its tree.

One by one the elephants took turns covering the baby with palm fronds until the hole was filled. Until there was nothing left to do but stroke their trunks against the mother and wait for her to get up again.

Thais believe in ghosts. Even the highly educated, even the ones who swear they don’t. The threat of a ghost can shut down a market or a major thoroughfare. The sighting of a ghost is a solid reason to call in sick to work. “Gua pii” is a perfectly valid excuse for various personal shortcomings.

Radchana believes in ghosts only in Thailand. For years that baby elephant visited her there. It would show up in the jungle or at the market with its flappy ears and wet nostrils, only to disappear when she whipped around. She saw its eye—big and brown and unnervingly human—in every window and mirror. And then she would go home to New York and forget her ghost.

In America, she is not afraid. Or was not, before. She has not been back to Thailand since before she married Sam more than five years ago. She gives to Chiang Mai Elephant Sanctuary. She tells tourists not to ride the elephants when she visits. She did up her son’s room in an elephant theme so he would know where he came from, what to value, what to respect. She keeps the story of the elephant she sees, the elephant she didn’t even try to save, a secret for herself alone.

Now, thirty-four years old and far from the jungles of her youth, she is not afraid of her own personal pii. It’s just a baby. It just wants to play. It is with her in the car as she closes her eyes against Laura’s shock. It is with her as she puts the fruit away, the light bulbs that will fit no fixtures in this house, the turkey bacon, the single washcloth, the coil of clothesline, the set of tiny spatulas, the half-melted ice cream. It is with her, flicking its little tail, waving its little trunk around as she haunts the door to the nursery. It shakes its little head and parades around Sam, who is asleep on the floor beside the bassinet, tear tracks glistening on the face Radchana had once loved so well, but now cannot picture clearly. He’s blank in her mind, a chalkboard wiped with a dirty cloth. The baby elephant hops into his arms and disappears into Chang, who is still clutched to Sam’s chest as if it were a ventilator, as if it could give him his breath back, his pulse, his son.

Radchana lets her mother’s calls go to voicemail three times before she steels herself and picks up.

“Why you don’t answer me?” Mae says. “I gonna call police.”

“I’m fine, Mae.”

“You not fine. Your friend call me, say you crazy.”

Radchana rubs her brow. She sets the phone down and puts it on speaker, low so the shrill scrape of her mother’s voice doesn’t wake Sam. Her mother rants on as Radchana rinses the ngô and sets them in a colander before beginning the painstaking peeling process. Her mother, her grandmother, her aunts and cousins and all the neighbors, could pop out the fruit with no effort at all, suck the sweet flesh off the pit and spit it out without a thought, next fruit at the ready. Radchana had never learned the trick to it. She doesn’t even like ngô, but she enjoys the perversity of their reaching alien tentacles, the shivery feeling of their skin against hers, the cheery riot of color.

“Are you listen to me?” Mae says.

“She was bothering me, Mae. I don’t want to talk to people from work whenever they see me in public—that doesn’t make me crazy.”

“She say you have a breakdown.”

“Well, I didn’t.”

“You go to hospital,” Mae says. “Make sure you not cuckoo.”

The ngô slide away from Radchana’s fingers like anxious eels. She lets them drop into a bowl one by one as she collects the peels—now round husks, surprised to be empty.

“I gotta go, Mae.”

“I come over.”

“No, please,” Radchana says. “Just give me and Sam some space.”

“I clean up for you.”

Radchana sweeps at her brow again and leaves a smear of sticky juice there. She swears and wipes her face into her shoulder.

“Don’t talk to Mommy like that!”

“Mae, I didn’t,” Radchana says. “I just made a mess is all. Look, I gotta go. Don’t come over.”

“I cook.”

“Mae, please. Please just stay home.”

Radchana’s mother switches to Thai and pitches her voice low.

“Be nice to your mother who has done so much for you your whole life,” she says. “Go to the wat and pray that your karma doesn’t kill your next baby. Pray your farang husband doesn’t leave you.”

“There’s no wat here, Mae.”

Radchana ends the call with wet, sticky fingers and blocks her parents’ home number, and both their cells while she’s at it.

She washes her hands and spreads out the ngô peels. She hovers her palm over the tips of their tendrils and pets them like she might the coarse, upright hairs of an elephant.

Sam collects himself and slides past her in the hallways when she tells him there’s fresh ngô to eat.

Radchana cannot sob at the edge of the bassinet. All she can do is stare until her eyes, dry and burning, threaten to fall out of their sockets. All she can remember is that before she called 911, she called her mother. Before she shouted for Sam downstairs, she plucked Chang from beside the corpse of her newborn and hid it deep in the closet. Before the ambulance came. Before the baby elephant came back.

Long after sunset, Sam is the one in the doorjamb, Chang slung in the crook of his elbow. His face is shadow on shadow.

“Oh,” he says. “Are you going to be much longer?”

Radchana’s mouth twists into something ugly. An odd fruit peel with its flesh torn out.

“Go eat something,” she says. “You look like shit.”

Her vagina hasn’t healed from giving birth yet. The last time they had sex was the night before Cameron died, the both of them too impatient and full of the kind of love that makes a family to abstain for the approved period. She had been aching for him and he in awe of the overflow of her breasts, the swell and sag of her slack belly. He had sucked greedily at her swollen clit and she’d come in waves, bucking against him and wrenching his hair, pure bliss expanding from the base of her spine like a dying star.

She cannot reach for that feeling now. All she feels when she encounters him is a vertiginous nausea.

“Come on,” he said. “Don’t be like that.”

“You don’t be like that!”

“Radchana—”

“You’re in here all day! All day every day! Let me have a fucking go at it, for fuck’s sake!”

He turns away. Radchana’s throat is so dry she fears it may crumble and collapse into dust.

“I’m sorry.” Sam’s voice breaks. He’s thumping his forehead against the jamb.

“Don’t do that,” Radchana says. “You’ll hurt yourself.”

“Look at you,” he says. “Always taking care of your Samwich.”

She leans her hands, the whole of her weight, against the edge of the bassinet.

“Don’t do that either,” she says.

The thunderous crack of a tree crashing down outside makes them jump. A siren blares. They go to the window and move the curtains aside.

An Asian elephant stands tall and serene on their lawn, casually eating their Japanese maple. Another lumbers down the street touching its trunk to each mailbox it passes as a police car creeps behind it. Behind that, two camels stroll side by side.

“Jesus Christ!” Sam says, even as Radchana lets out a scream that rattles the windows. There is something essential, a self unanchored, that lifts away from her and rises to the ceiling where it watches, breathless, instead of dissipating. Is this elephant her pii made manifest, or is she now the pii in her own life?

The elephant snaps a branch off the tree and swivels its ponderous head towards her. Its great kind eyes, amber by the light of the streetlamp, see into the husk of Radchana’s body and do not flinch away. Its trunk reaches for her and drops again, and Radchana crashes back into herself. She heaves for breath against the thundering of her blood, the cascade of stars behind her eyes, the prickle of gooseflesh that rises along the borders of her body. The elephant turns back around and saunters into the next yard.

“That’s circus security for you!” Sam says, and then he’s laughing. Radchana risks a glance at him, and the sight of his one imperfect tooth, snaggled askew against the rest, hooks her belly like a goring tusk. She laughs so hard tears stream down her face. She doubles over, clutching her belly, and then shrieks as she loses control of her bladder. Urine splatters across the hardwood, which makes Sam laugh harder.

When they can breathe again, they catch each other’s eyes. Radchana’s mirth fades, and she is suddenly mortified in sodden sweatpants. Sam tries to hand her Chang as if it’s a tissue to soak up all her snot and tears, but she recoils.

“I’ll clean that up,” Sam says. He wheels abruptly away, and Radchana lays her head against the window. The neighbors have clustered on the curb to watch the cops in their own private circus act.

Behind her, Sam soaks up the urine and sprays it with Windex, then wipes it away with paper towels. He approaches her like the cops approach the elephants, and she tilts her body toward him but stares, unseeing, at Cameron’s mural. Sam eases the elastic waistband over her hips and down her legs. He helps her step out of them.

“Sam,” she says.

On his knees before her, he asks, “Are we gonna be okay?”

Radchana’s gaze slips away. The cops and the elephants and the camels turn the corner and leave her sight. There is a trail of broken branches and trampled flowerbeds and battered trees in their wake. Chang appears in the corner of the room to flick his ears and wave his trunk, two hundred pounds of organic cotton. Radchana meets his shining button eyes.