The Temperate Zone

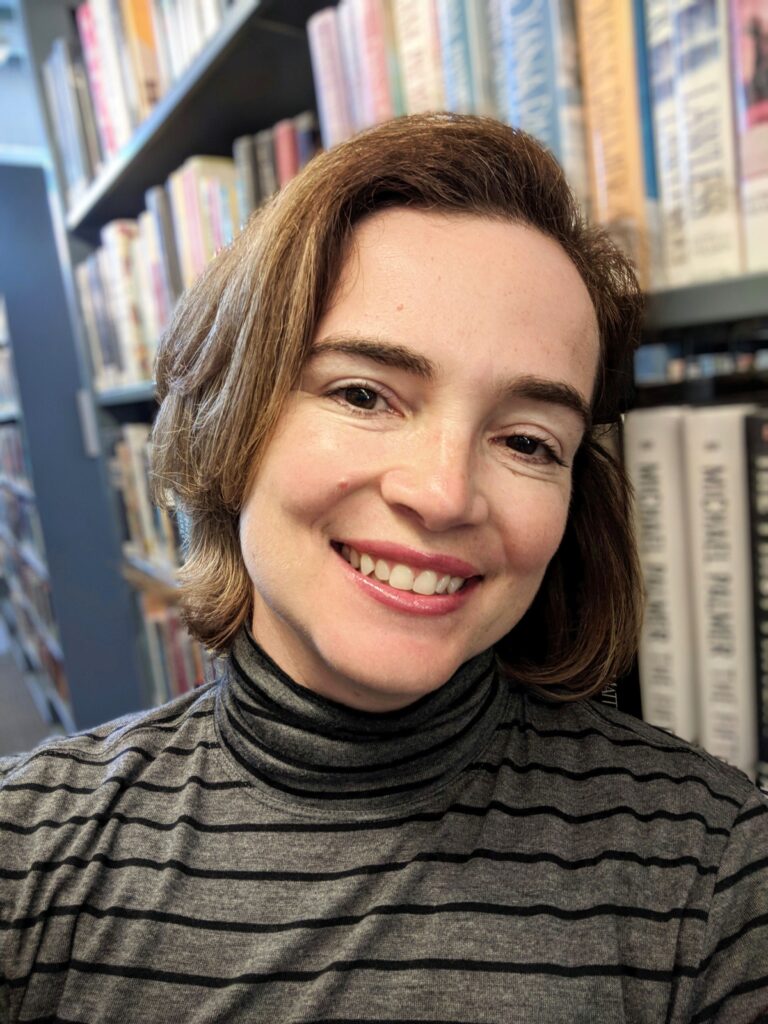

Sara Joyce Robinson

On Tuesdays, I clean the house. Once I have tidied and scoured and swept, I rub oil into the old wood. I wash the windows pane by pane, including the stained glass in the turret. I straighten the fringe on the rugs with a comb. My final task is to polish every handle with disinfectant and a soft cloth. There are eight hundred and thirty-four handles in the house, on doors and cabinets, appliances and drawers.

My mother’s great-grandparents built the house in Pasadena before the turn of the last century. While the acres of oranges trees were sold off two generations later and transformed into grids of bungalows, the house contains much of the original furniture.

At least once a year, the Historical Society asks if they can include my house on their tours. I always decline.

With my inheritance, I could hire a crew to clean. But I enjoy the work, and when I’m done I can stand in the center of my house, and know that it is clean, that any mark I might have made has been wiped away. Afterwards I walk to Emilio’s Ristorante to enjoy one of their twenty-six pasta dishes. I don’t go grocery shopping until Wednesday, and it’s important that I leave the house once a day.

Today, as usual, I polish the handles last, beginning at the top of the house with the former servants’ quarters. The man I’m seeing now is supposed to call, so I listen for the phone as I spray then rub each knob upstairs. I am careful not to touch them with my fingertips afterwards.

Eugene is a race car driver, so most of the time he’s away, traveling the circuit of lesser-known tracks as he tries to break into the big leagues. We met two years ago at the café I walk to on Saturdays to read the newspaper. The café was packed, so Eugene asked if he could share my table. I nodded without looking at him.

After a few minutes, he asked, “What’re you reading?” “The international weather,” I answered.

“What’s today’s forecast?”

This question made me look up. Most people in Pasadena aren’t really interested in the weather. I was surprised to see how large Eugene was, not overweight, simply oversized for the café chair. The mug in his hand looked tiny. He wore dark jeans, a tucked-in plaid shirt, and a fancy belt buckle with a soaring eagle.

“Sunny with a few clouds and a westerly breeze,” I told him.

Eugene regarded me steadily to see if I was bluffing, but I never joke about the weather. When he saw I was serious, the corners of his eyes crinkled as his lips widened in a smile. I caught a flash of white teeth.

He leaned toward me to say, “That must be the forecast every day in California.”

This prompted me to explain how there are seasons in Pasadena, like anywhere else, they are simply subtler. They require a discerning palate. Eugene is from Montana and seemed genuinely interested, so I told him about global weather patterns, how pressure zones carry temperature changes.

When he had to go, he asked if I’d be at the café the next day.

“Sundays I go to church,” I told him, “But Tuesday nights I eat at Emilio’s down the street.”

He let his smile warm his face. “I like a woman who keeps to a schedule.”

Two Tuesdays later, Eugene was waiting for me at Emilio’s with a bible. It had a maroon cover stamped with the words Property of the Trade Winds Motel, North Dakota. When he gave me the bible, he said it had reminded him of me. I told him that dry winds were predicted for the next three days.

It took six weeks and four dates before I learned about the race cars. We were at Emilio’s again, when Eugene set down his forkful of chicken parmesan. “I think I’ve been dishonest with you.”

I straightened the knife lying next to my plate. “The weather in Peru is seasonably warm,” I told him, “Highs in the upper-eighties.” This had happened to me before. Men lied, told me not the truth, but what they thought I wanted to hear. Although usually, they did not volunteer this information, rather I had to discover it through my own devices.

“I haven’t purposefully lied,” he pressed on. “I know you don’t drive, so it was easier to say nothing. But I like you Amaryllis, and I hope this doesn’t change that.” Then he explained about the race cars. How he started on soapbox ones as a child, then ranch trucks over Montana fields, and finally the real thing.

As he spoke, I looked out the window of the Ristorante and studied the lavender quality of the evening light. I knew I had that one moment to choose between the race cars and all the warm promise inside his smile. I knew that once I decided I could not take it back.

When Eugene stopped speaking, I commented that tomorrow in Southern California early morning clouds would give way to sunshine in the afternoon.

He took my hand in his larger one. “So it’s alright?”

I nodded and told him my own dishonesty. “I don’t go to church on Sundays for the Bible but to visit my mother’s grave. She died in an accident when I was small and left me and my father alone in her house.”

Eugene’s face was serious as he held my hand between his palms, infusing my fingers with his heat. Then I invited him into my house for the first time. We went up the stairs to the blue bedroom where I sleep and learned the boundaries of each other’s bodies.

Now whenever Eugene returns from the circuit, he brings me a bible from one of the motels he’s stayed in. To say he’s thinking of only me in all those small rooms with patterned bedspreads and fiberboard furniture. I stack the bibles against one wall in the front parlor and dust them each Tuesday. Most are maroon or navy, but I have three green ones and one pale blue bible from the Chicken Coop Motel in Butte.

Eugene has been all over the country, to Europe and Japan, and has seen weather I have only read about. I have never left California, rarely been outside Pasadena. I tell myself that when the bibles get to a certain height, I will go with Eugene on one of his trips. But when they do, I decide to set another goal, higher than the first. When he comes back from this trip, I’ll have to start my fourth pile of books.

I’m finishing the handles of the drawers in the antique dresser in the master bedroom when the telephone rings. I hurry downstairs to the white princess phone in the kitchen. It once resided in my mother’s teenage bedroom. She lay across her bed in low-slung jeans, the wide hems ragged and caked with dirt, and talked to her friends through the same receiver I now lift. It is heavy, a solid weight between my ear and shoulder. I have not cleaned the phone yet, not until after Eugene’s call.

“Hello,” I answer, “This is Amaryllis Foster.”

“Hey Mary,” Eugene’s voice is deeper over the phone than in person.

“Eugene,” I savor the feel of his name inside my mouth. I stretch the telephone cord across the kitchen to clean the handle on the refrigerator. The kitchen is the one room in the house that has been modernized with new appliances, though the wood cabinets are original. “Where are you?” I spray then polish.

“Little Rock. We’ve had blue skies today with temperatures in the low to mid-seventies, but there’s a chance of showers tomorrow. How about you?”

“Sunny with a few clouds and a westerly breeze.” I can hear him smiling all the way across the country in Arkansas. I always give him this answer, even if it’s raining or blisteringly hot. We have made it a promise between us.

“I raced today,” he says quickly. “I did alright, not a win, but I came in ahead of that guy from Cincinnati. I think the new tires make a difference.”

I walk across the kitchen to reach the knobs on the pantry door. I never ask Eugene about his races and say nothing as he describes a win or a loss, occasionally a close call of screeching tires, metal tearing and bending, hot fire pluming up. He doesn’t include those details, but I know what happens at the epicenter of a crash.

“Hmmm,” I manage to murmur before I tell Eugene about the rain that swallowed a village in Vietnam, as well as about the humidity in Panama that is raising concern about late season mosquitoes and fever.

“A good day for weather,” he says. “And cleaning.”

Eugene knows that on Tuesdays I clean the house. Both of us prefer to spend time here rather than his place in a complex of furnished condos. Because he is gone for weeks, his rental agreement shifts him wherever there is room when he returns. Every time I have visited, his apartment has been a different unit within the complex. Because each place is decorated in the same way, with only minor changes in layout, I have an eerie sense of déjà vu. The same beige couch, the window on a different wall, the potted plant taller or shorter.

“Yes,” I agree, “I’m already polishing the handles.”

Next, he will tell me where he’s going. It’s one of the things we’ve worked out. He doesn’t tell me when he’s going to travel until the day before he departs. I find it helpful not to have too much time in advance to imagine him on airplanes or buses.

“So good news, I’m coming home tomorrow.”

I picture him here in front of me, breathing and live, his large hands reaching for my skin. “You need a few days off. You’ve been gone longer than usual.” The handles on the kitchen cabinets have a delicate design embossed into the metal, so I have to rub vigorously to get into the fine lines.

“Well,” there’s an anxious note in his voice. “My news is really good, I have a race in Long Beach.”

Since we’ve been together, he’s never raced in Southern California, so I’ve never seen him behind the wheel of his race car. I set the bottle of disinfectant down before I drop it.

“Mary, are you there?” he asks.

“Yes.” The word is very small.

“I hope you’ll come to my race. It’s at night, so you can take care of whatever you need to during the day. I’ll pick you up.”

To stay upright, I brace both hands on the counter. I cleaned the tile this morning, first with disinfectant, then powder bleach, and finally with a toothbrush to get at the lines of grout. My prints are all over them now, so I’ll have to do the whole process again.

“Mary,” Eugene says, “Amaryllis, please.”

The kitchen tile is cold under my palms. “Washington, D.C. is experiencing an unusually pleasant summer. I didn’t mention that before.”

“I have a ticket for you,” his voice is soft but insistent. His words bite into the back of my neck. “Roadside in the VIP box. You can close your eyes during the race, I don’t mind. This could be my big break, and I want you with me.”

My breath is too shallow, light.

“Don’t decide now,” Eugene says, “I’ll be there tomorrow at four. Don’t decide until then.” He pauses. “I hope you say yes.”

Eugene waits for me to say something. I can hear him breathing in Arkansas, and I mouth the word he wants, Yes, though I can’t find enough air to make a sound.

“Okay Mary,” Eugene says, “I’ll see you tomorrow.” The phone buzzes its disconnection in my ear.

~

I lie on the floor of the front parlor, on the polished hardwood planks I waxed by hand this morning and count out my hundred breaths. My legs are stretched over a rug

that my great-great-grandfather brought with him over an ocean and a continent and into this house. The tassels I combed straight earlier are tangled once again.

The crown of my head almost touches the stacks of Eugene’s bibles. It is quiet in my house, except for the ticking of the grandfather clock. I take the last of my hundred breaths and run my hand down the spines of the bibles.

They do not really belong in the front parlor. They clash with the delicate furniture, the nicest pieces my great-grandparents owned, the ones to impress guests. But I like them here, in a public part of the house, rather than in the room where I sleep. They are my addition to the house, evidence that I inhabit these rooms.

Sometimes I think I should arrange the bibles by color, order them in a repeating pattern, maroon, maroon, navy, maroon, navy, navy, green, a kind of Morse code. But then I would have to disturb their original chronological arrangement, in the order Eugene brought them home. I’ve written the date on the inside of each one and put them in three stacks of ten, which is thirty times Eugene has come back to me.

For my fifth birthday, the last one my mother was alive to see, she took me to the circus. Our seats were in the front row by the center ring. The only thing I remember is the man who put his head inside a lion’s mouth.

To perform the trick, the lion tamer asked for silence from the crowd so as not to disturb either his, or the lion’s, concentration. He approached the beast slowly. I could see sweat bloom across his forehead. The lion was a fierce golden beast, easily four times the size of the tamer. I could tell the man was afraid, with a deep and cold terror, even though he matched the lion’s measuring gaze. In one smooth movement, the tamer gripped the lion’s upper and lower jaw and slid his head into the darkness of the open mouth.

I gasped as light gleamed off the lion’s white incisor, now bared and digging into the man’s forehead. For a moment, I felt the press of the lion’s teeth into my own flesh, the hot dampness of his breath, his tongue wet against my cheek, the shadows waiting to swallow me.

I turned my face into my mother’s shoulder, searching for the warm cradle of her body. But she did not curl around me. She did not wrap me in her arms. She was tense, unyielding, unaware of the chills crawling across my skin. I pulled on her sleeve, but her eyes remained fixed on the lion and his tamer. She leaned toward them, as if caught in their thrall.

In the center ring, the tamer slid his head free from the lion’s jaws. He took three steps backwards as the lion stretched his mouth wide and licked his whiskers. The tamer spun toward the crowd to raise a triumphant fist.

There was a red groove on his forehead where a sharp tooth had dug a mark into the skin. And in his eyes I saw longing for the next day to come, so he could once again put his head in the lion’s mouth.

I recognized that hungry look. It lived in my mother’s eyes as well.

On the floor of the front parlor, I wedge my hand into the middle of a stack of bibles, to sandwich my fingers between books.

Tonight, I will not walk to Emilio’s for dinner. I will not finish polishing the handles in my house like I do every Tuesday. Instead I will lie here with my bibles and wait until it is tomorrow and Eugene is in California again.

~

From the passenger seat, I watch Eugene concentrate on the sluggish traffic creeping along the tangle of freeways between Pasadena and Long Beach. His fingers tap the steering wheel in time to Elvis singing on the radio.

The truck Eugene drives as a civilian is a 1953 Ford. Its bench seat is wide and sprung like a sofa, and its body is finished in a classic turquoise, the color of swimming pools. When the speedometer goes above fifty, its whole skeleton trembles, so Eugene has to drive slowly, and I don’t mind too much.

I waited for Eugene outside my house. Before I left, I checked the lock on every window and door twice. I hadn’t finished my Tuesday cleaning or started today’s work in the garden, pruning rose bushes, picking oranges, filling the birdfeeders. I stood just beyond the white fence that encloses the front lawn. My father used to wait for me in that same spot whenever I left, to walk to school or the store. He stood with his shoulders hunched inside a sweater, eyes nervous and searching, until I called his name and came inside the gate. After my mother’s accident, he found it hard to go outside, and so conducted his business, monitored the investments that are now mine, over the telephone. My father only left the house once a week, on Sundays, to visit my mother’s grave.

When Eugene drove up, I got in the truck before he could say anything. Now, as we inch along the freeway, my hands grip the bible Eugene brought back from Arkansas. It’s an old one, the binding cracked and the pages yellowed. The cover is orange. On the inside, the words Shoehorn Pete’s Roadside Motel are stamped in faded ink. Eugene told me this was not the name of the motel he was staying in, which means the bible is a hand- me-down, one bought used after outliving its original owner.

Eugene darts a look in my direction. Today I am dressed in black. I wear sunglasses and a silk scarf that belonged to my grandmother when she was a young wife, glamorous on her way to the beauty parlor, to the market to buy eggs. Eugene and I haven’t spoken in half an hour.

Usually our silences are good times. I study the weather while Eugene contents himself with his own interests, automotive magazines and his book of bird-watching. I haven’t met many people who can do that. Eugene claims his patience comes from the long Montana winters of his childhood, where months of snow locked his family indoors together with no break. Our silence today is not easy.

“Do you like it?” Eugene asks finally, nodding at the bible in my hands. “It’s beautiful,” I tell him, “Thank you.”

“Thought you’d like it. It’s different from the others.”

I feel the texture of the bible’s binding with one finger. “In Long Beach today, it’s sunny with a brisk on-shore breeze and surf of two to three feet.”

Eugene smiles, as traffic coasts to a halt. “I’m glad you came Mary, it—”

“A twister,” I interrupt. “A twister cut across southern Illinois just before dawn, destroying thirty-four homes, killing two people and nine sheep.”

Eugene’s smile fades, and he shifts the truck to let it move forward a few yards. “Are you sure you want to do this?”

I keep my eyes fixed on the bumper in front of us. “Please, just drive.”

Eugene says nothing, but I see his hands tighten on the steering wheel. His shoulders shift under his plaid shirt. After a moment, he turns the knob on the radio, silencing Elvis, searching until he finds the right station.

“Light afternoon showers in Vancouver will last into the evening.” The weather man’s voice is smoothly professional. “Paris is enjoying clear weather with low humidity and blue skies. In Jakarta, they broke the record high temperature for this date, in place for almost forty years.”

~

My seat in the enormous bowl of the stadium is curbside in a box reserved for the families of drivers. Only a swatch of chain-link fence separates us from the open darkness of the racetrack. It smells like popcorn, fresh pavement, and gasoline. I wear my sunglasses and scarf even though afternoon has slipped into evening, the temperature dropping along with the fading of the light.

There are seven other people inside the VIP box. Three are young women with tight plastic breasts and frosted hair. Two discuss a bridal magazine, while a third examines her polished nails. An older woman, maybe a mother of one of the drivers, sits knitting a shapeless purple sack. A middle-aged man with a generous belly types on his cell phone. Next to me, another woman holds a small boy. She has a round face and looks tired. The baby gnaws on a slimy piece of bread. When Eugene brought me in here, the women greeted him casually, as if they were meeting in the aisle of a supermarket. They have clearly done this many times before.

The baby is watching me as his mouth works over the bread. His cheeks are flushed and his eyes bored. I thought small boys were supposed to be interested in race cars. I should smile at him, but can’t make my mouth move. The older woman’s knitting needles click rhythmically over the noises of the crowd filling the stadium.

Out on the track under the glare of the lights, the cars for Eugene’s race are being prepared by a swarm of men in overalls. From a picture Eugene has shown me, I know which one is his, cherry red, with a logo for cinnamon chewing gum spread along each flank. On the hood, the number five is painted in white.

A roar gathers in the stadium as the drivers, five men and one woman, parade onto the blacktop. Each driver wears a jumpsuit that matches the color of their car and carries a helmet under one arm. They wave at the crowd with their free hand. As the drivers pass our box, they nod to the person who is there for them.

When Eugene nods at me, I see in his eyes fear, tightly controlled, but hungry and twisting under his smile. I grip the orange bible tight, until the edge bites into the meat of my palm.

Eugene stands by the nose of his car and listens to the words of a man in a red bomber jacket and baseball cap. His shoulders are tense when he slips on his helmet. The swarms of men recede from the race cars. Eugene rests his hand on the hood for a moment with his head bent, and I wonder if he’s praying. He turns to brace one arm on the top of his car’s open window and the other on the bottom, then swings his large frame up and through the window. For just a second, I think I see his face, eyes closed, muscles loose, lips parted slightly in a smile, fear erased, but then he disappears into the shadows of the car’s interior.

Before I’m ready, the engines roar to life in a terrible cacophony. The last few men on the track sprint toward the sidelines. A horn sounds, and the crowd screams. A checkered flag rises in front of the race cars, and there is a moment when nothing has happened yet. Then the cars leap forward.

Their first revolution is well-mannered. Their speeds are low, and they stay in line. On their next turn, they push faster, until on the third pass, the race cars let loose. Their wheels scream as they fight for purchase on the pavement, and the whine of their engines builds in a fierce, gathering growl.

When the cars flash past me, I can’t find Eugene in the smear of colors. The others around me lean forward. Their eyes know how to chase one car. The small boy squeals, arches his back. His mother bounces him on her arm without moving her attention from the track.

I close my eyes so I am with Eugene inside the race car, cupped by the dark interior, strapped in across my chest, the steering wheel stuttering under my palms. There is a terrible click outside the cage of vibrating metal, as the car’s fender catches against another. The race cars growl, struggle for supremacy, until they jump away from each other, spinning up and over.

The fire leaps out. I think of Eugene’s body inside his jumpsuit, unmarked and warm and alive, the muscles dense as they stretch under his skin and tense against impact. His body is not strong enough to resist the advance of metal cutting through his flesh, biting into sinew and bone.

Beside me, the small boy squeals. He shouldn’t watch this. Instead his mother should take him away, at least gently shield his eyes, so he does not have the image of the crash inside his mind. He is not too young to be haunted.

I release the bible with one hand and pull the sunglasses off my face. I force my eyes to crack open in the glare of the stadium lights. I blink until I can make out the line of race cars moving quickly on the far side of the track.

There is no smoke, no fire, no carcass of mangled metal. Instead, an orange race car is several lengths in front of a blue one, with red number five closing in. The stadium crowd is on its feet.

Eugene edges into second place behind the orange car, as a horn blows and the stadium erupts into wild screaming. One of the young women claps and jumps to her feet. Her tight breasts do not bounce inside her tube top as she celebrates. The race cars slow on the track and pull to a stop.

As the swarm of men descends upon the cars, I understand it is over. The others pack up their belongings. The older woman stuffs her purple knitting into a large sack. The woman with the baby leans her cheek against the back of his head for a moment before she hauls herself up. Somewhere out in the stadium, a man announces the official rankings over the loudspeaker, and draws one last roar from the crowd.

I see Eugene striding across the pavement towards where I sit in the box. He’s removed his helmet, but I can see the grooves where the chinstrap marked his skin. He grips the chain link and pulls himself upward, until he’s over the fence and down in the box, his body lithe and coiled in the air. His hands find my arms and yank me up to him. His body runs hot, like leaning into the sun. There is roughness in his touch, and his teeth catch my bottom lip and scrape slowly to release it. I taste the tang of his sweat.

“Second place!” He grins down into my face. I put my index finger on the indentation of his chin. “I’d hoped for third as an outside chance, but never expected this.”

I meet his eyes, and under his giddy energy, his triumphant joy, there is a residue of regret. The tug inside him that longs to be back inside the race car, inches away from darkness.

“I’m so glad you’re here Mary,” he adds. “I felt you in the stands the whole time.

What did you think of the race?”

There are many responses I can give him. There are tornados in the Gulf of Mexico today. An earthquake split through the Philippines this morning, predicted by nine consecutive days of hot rainless skies. The polar ice caps are melting. Tomorrow in Pasadena, it will be sunny with a few clouds and a westerly breeze.

I lay my palm against his chest to feel the heart beating there, quick and regular. “I was terrified,” I whisper.

Eugene pulls me against the warmth of his chest, rests his chin on my hair. “I know,” he says. “Thank you.”

~

Sometime deep in the night, I leave Eugene sprawled in my bed. In the dim bedroom light, I can see the topography of his bare back, gentle slopes, a ridge of spine, rivulets of muscle.

I walk naked through my house, into every room, upstairs and down. Moving through the rooms without lights, I touch all the old things with my fingertips to make sure they are still there. The headboard of a bed, the arched back of a couch, a Tiffany lamp, the corner of a silver picture frame, the painted basin of a bathroom sink. I leave my fingerprints on each one.

In the kitchen, I find the spray bottle of disinfectant and the soft cloth lying where I left them the day before. I decide to start setting the house right while Eugene sleeps. I

think of all the things we’ve touched since we came home from the racetrack, and how they all need to be washed.

Experimentally, I turn the disinfectant toward me and spray a mist over my naked chest. Over the spread of white lines across my ribs, the web of long-healed scars marking my skin. The spray is cold and smells clean.

I wipe the cloth lightly over my breasts, just to feel them feeling the cloth, to know that I am still here.