Homebody

Jessica Dealing

(July)

The house seemed to dare Amber to approach, the top two windows a pair of narrowed eyes on its otherwise closed face. She would too as soon as the landlord showed up. The rent was so low even a recent college grad with no prospects like herself could afford it.

The clock on her dashboard was still an hour behind since the switch to Daylight Savings. She couldn’t figure out how to change the damn thing, and by the time she did it’d only be time to switch it back anyway. You couldn’t win.

While she waited, she tried to imagine peering out of those windows to the street below as if she lived there already. Her therapist, during a brief stint, suggested visualization as a powerful tool of success, whatever she meant by success. It was one of the reasons Amber had stopped going—their opinions often differed.

Surely it didn’t entail having to get her job back from the grocery store because she quit prematurely, assuming once she graduated the job offers would roll in as if they already knew about her and were waiting, breath bated, for the officiality of a college degree. The assumption could be traced back to her father, who had always said, or at least implied, that college graduates were in demand, economically speaking. That he didn’t have one might explain why he placed such bloated value on it, the way one’s lack can become their focal fixation.

Something inside the house scurried past the window, and Amber jumped, goosebumps prickling her forearms, unable to resist wondering if she just saw a ghost.

When an elderly woman opened the front door and stepped onto the porch, Amber exhaled. The landlord. Landlady, she supposed. What’s-her-name. M. Mandelbaum was all it said in the newspaper ad—clipped and sitting on the passenger seat for proof, lest this woman try a bait-and-switch—her gender indecipherable till now.

If she were being honest, the whole thing seemed a bit off. Their correspondence, for one, by post, for godsake: no email address or even phone number was given, and Amber wondered now if this woman, vaguely Victorian in her long skirt and collared top, even owned a computer or, for that matter, a telephone.

Flakes of rust fluttered to the street as she shut her car door and, stuffing the ad in her purse, she made her way to the house, conscious of the damp crescents under her armpits she hoped could be mistaken for shadows.

“You’re late,” the woman said in a voice like crumpled paper. She appeared more concerned than angry.

“No,” Amber insisted. “See, I was waiting in my car. Sorry—I guess I should’ve come up to—”

Presumably-M.-Mandelbaum waved a hand, stopping Amber midsentence. There were no signs of perspiration on her heavily powdered face, or elsewhere, despite her long dark clothes in the muggy afternoon. Perhaps she was one of those old-school Floridians who, accustomed to the extreme heat, were known to forgo AC.

“I suppose you want to see the place,” she said.

Amber followed her upstairs, their footsteps echoing on the wood. Mandelbaum’s hands badly shook as she drew a key from a skirt fold, and she fumbled with the lock while Amber waited on a stair two below, creaking under her weight as she shifted from one foot to the other in suspense.

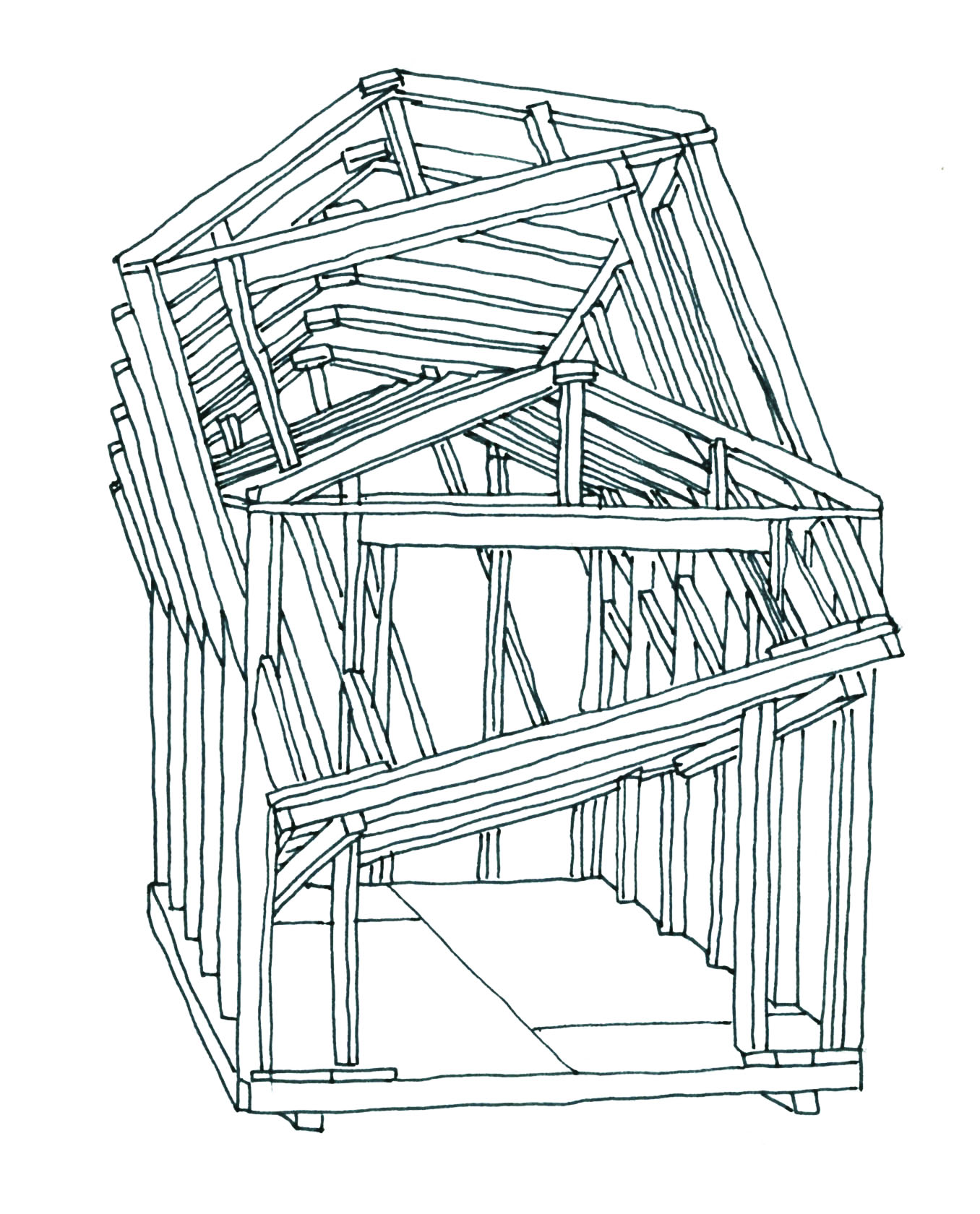

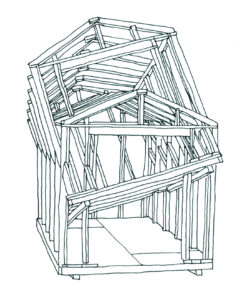

Finally, the door opened and the pair stepped into a large, bare room that steepled above them in a crosshatch of exposed rafters.

“You have a neighbor below you,” Mandelbaum was saying. “But don’t worry, he keeps to himself.”

On the contrary, it was the first time she’d be living alone, and the idea of someone else in the house comforted her.

A grumbling noise bellowed from the walls, startling them both. Mandelbaum recovered as if she had heard the sound many times. “Just the pipes,” she said, a smile plastered in place.

(August)

In the end, she had signed a six-month lease, scheduled to end just after the holidays and thus giving her ample time to find a real job. Though officially the lease began mid-August, the Mandelbaum woman let her move in right away, nearly three weeks ago. In all that time living in the top half of the house, Amber had yet to lay eyes on her alleged neighbor. Every now and then she thought she heard something, low groans rumbling through the floorboards, like someone dragging heavy furniture across a room, and assumed her neighbor liked to redecorate often. Or maybe it was just the pipes.

In anticipation of her friend’s visit, Amber sashayed from room to room in a mist of lemon Pine-Sol to Barry Manilow’s Greatest Hits. She could only stand Barry Manilow when her mood was exceptional, but if anyone asked, she’d deny it up and down.

When she came to the mirror in her bedroom, she stopped. Full-length and framed with ornate gold vines, the mirror had been there when Mandelbaum had shown her the unit, and when it still hung in place the day Amber moved in, she chalked it up to an oversight. If it wasn’t antique, it was at least expensive, and she planned on taking it with her when she moved out. Except now, she saw that the glass had developed several unsightly black spots in the upper corner. It looked like mold, but when she tried to wipe it away with a rag, she could feel that whatever it was had eaten into the surface, blemishing her reflection’s forehead like a bad apple. It was just her luck, really. Everything around her turned to shit eventually.

Lucy arrived on her doorstep in a yellow sundress that took her breath away. Since when had Lucy become so sophisticated? When they were roommates in college they’d often spend the entire day in pajamas, sometimes even the days they went to class. In fact, of the two of them, Lucy favored the sloppier, more comfortable clothes, often throwing her hair up in a knot instead of brushing it out. Now she was working at her dad’s firm across the state, while Amber, the overachiever, still worked a bullshit teenager job. This wasn’t supposed to be her destiny. It was like they switched places.

Of course, she couldn’t tell Lucy any of this. Instead, she threw her arms around her friend and gave her a tour of the attic.

“It’s…nice,” she said with a smile that was too reassuring.

“Well, anyway, it’s only two hundred a month.”

“What! Who would rent anything for so little!”

“Some little old lady who doesn’t have a clue.”

They walked to the corner store for wine and snacks, the way they used to when they lived together. At the end of the street they passed a phone booth, against which sat a homeless man feeding string cheese to a clowder of cats. Beside her, Lucy tensed.

“Maybe the rent’s so cheap because of the neighborhood,” she said, her gaze fixed on the homeless man.

Amber glared at her and waved to the man, who—despite his disposition to the cats—squinted at them in steely silence before raising his hand a hairbreadth. She jumped at the chance to defend the neighborhood. Her neighborhood.

“See?” she said. “It’s perfectly friendly.”

“Still, I don’t know why you couldn’t just move back home till you found something.”

It was out of the question. Going back was just that, going backward. It would be like admitting defeat, and she’d rather die than do that. Besides, with her rent being next to nothing, Miami was as good a place as any to sit and wait for the next chapter.

As they grabbed candy bars and bags of chips, a sudden and strong nostalgia hit her. What if this was the last time? Lucy with her Snickers bar and Amber her Whatchamacallit. The one-pound bag of gummy bears they’d share between them. She wiped at her eyes discreetly as they paid and left, but she could feel Lucy’s gaze on her every so often as they walked along. A large cloud had covered the sun. The man and the cats were still at the corner, but the phone booth was gone.

“Hey,” Amber said, nudging her friend in the side with one of the bags in her arm. “What happened to the phone booth?”

“The what? There wasn’t a phone booth there.”

“There was!” She was sure of it.

“Are you feeling ok?”

Amber scowled. “I’m fine.”

“Anyway, who cares? When’s the last time anyone used a phone booth? Everyone has cell phones now. Well, except you, of course.”

Amber could never quite make the leap to adopt the technology, not even new anymore.

“Just a second,” she said, stopping. She turned to the man. “Excuse me, Sir, but do you know what happened to the phone booth you were sitting next to earlier?”

The man stared at them with the same squinted expression, as if he didn’t trust them. He didn’t say anything.

“Remember when we came up this way, fifteen minutes ago?” Amber prompted. “There was a phone booth behind you.”

The man whipped his head around to look behind him, first one way, then the other, and then continued to stare them down. “Listen, lady,” he said. “I didn’t see nothing.”

“C’mon,” Lucy said, giggling, dragging Amber away by the arm.

Amber had to tear her eyes from the patch of grass where her memory had betrayed her. When she finally did, Lucy was studying her.

“The Publix job isn’t forever, you know,” she said.

Amber shrugged her cardigan from her shoulders. Although the sky was still sunless, the air was hot and thick around them. “Of course.”

(September)

Dragging the trash to the curb one night, Amber, from the corner of her eye, saw a man standing behind her, and jumped, dropping the bags in a clump at her feet.

“I’m sorry,” the man said. “I didn’t mean to frighten you.” He was short and slight of frame. She could take him if she had to.

“Who are you?” she said.

“Ed Zaman. I live here.” He held up his keys.

“Jesus,” she said, dropping her guard. “I didn’t even see you.”

Ed scratched his bald head. “It’s funny you should say that.”

She arranged the garbage bags on the terrace and headed back up the driveway toward the porch, unlocked the main door.

“Not really, the fog is like pea soup. What’s funny is that it’s only the first time I’m seeing you.”

“Yes, well…I don’t go out much anymore.” Ed slipped past her and opened his inner door. As she stepped into the foyer behind him, she couldn’t help peeking past him at his living space. She thought she could make out a bookcase inside.

“Where’s your car, anyway?” Amber asked.

“I don’t own a car. I have a bike.”

“Where’s your bike?”

“Inside.”

Amber eyed him up and down.

Ed stopped and turned. “Hey, do you know what happened to Ms. Arenas? She lived in your unit before you. I never saw her move out.”

“Well,” Amber said, heading up the stairs to her own floor, “she certainly doesn’t live with me.”

His voice carried up the stairs. “It’s just, I didn’t think she’d ever move out. She was pretty old, you know? And the last couple times I saw her she said how much she liked it here.”

Amber turned to face him, sitting on the creaky stair near the top. “Maybe she just changed her mind. This place is kind of a dump. Maybe she found something better.”

Ed chuckled and stroked his chin with one hand, the other still on his doorknob. “A dump, huh? You know, I thought so too at first. But this place, it has a way of growing on you.”

“You mean you like it now?”

“I never want to leave.” Without saying goodbye, he went inside and shut the door. Amber, from the stairwell, heard the click of a lock.

(October)

Getting her job back had been awkward. Although she hadn’t said much, Amber detected an air of smugness from Gayle, the manager, as she handed back to Amber the detestable green smock. To make matters worse, the only shifts available were the crappy mid-shifts nobody wanted—from eleven a.m. to eight p.m.—dividing the day just enough so you couldn’t do much before work or after, effectively centering your life around your job. On her daily commute, the sigh of traffic permeating the car windows, she’d invariably pass the Magic City billboard, never failing to cause Amber to roll her eyes over Miami’s nickname. Working in a grocery store was enough to convince her there was no such thing as magic in Miami. Probably not anywhere in Florida, unless you counted Disneyworld.

That’s at least what she thought till the first day the customers stopped coming to her lane. The day had started much the same as any other: the same—presumably—small murder of crows scavenging the parking lot for dropped French fries from the McDonald’s next door; Amber still holding the iridescent velvet of their feathers in her mind as she poked her head in the breakroom—Gayle preferred an early lunch, always the same home-brought sandwich squished to oblivion—to ask for her till. She could smell the salami from where she stood in the doorway.

The first two hours were always steady with people coming in on their lunchbreak for the quick item or two, and so it became obvious early on that her lane was being avoided.

Which was fine with her. In the first hour, she snatched a gossip magazine from the checkout display and hid a smile as she caught up on the latest sightings of Brad Pitt. But around noon, she glanced up from the magazine to find that lines had formed in the other lanes while her own remained a ghost town. She watched in disbelief as shoppers, their carts full, passed her empty lane to join a line in another.

Above her, the lane light was lit up like the beacon it was meant to be, and so she gave her armpits a quick whiff. Not that her deodorant had ever failed before, but if today taught her anything, it’s that there was a first time for everything.

It was only when she called across the gulf of empty lanes, “I can help who’s next,” did people begin to shuffle toward her, as if woken from a dream.

It was dark by the time she reached the house, and there was a moving truck in the driveway, a young couple unloading boxes from the truck. Amber parked along the street and hurried toward them.

“Excuse me, what’s going on?”

The couple turned to her, the man’s eyebrows raised, the woman’s furrowed.

“I live here,” Amber explained. “Second floor.”

“Oh, our neighbor!” the woman said, smacking her forehead. “We just moved in below you. I’m Nina, this is Will.”

The man, Will, set a box down and outstretched a hand, which Amber reluctantly shook.

“What happened to Ed?”

“Who?” the woman asked.

“The man who lived here.”

They stared at each other a moment, the couple’s expressions blank.

“Forget it,” Amber said, shaking her head. “I’m sorry. Nice meeting you.”

She felt them staring after her as she opened the front door and went inside.

Hadn’t Ed just told her he never wanted to leave? She lifted the phone from the receiver and dialed her friend. When Lucy picked up, Amber said, “There’s something weird going on—”

Lucy interrupted, sounding uncharacteristically agitated. “Haven’t you been getting my messages? I’ve been calling you for three days. I found a job for you. Some guy who does a local news show, my firm does his taxes. It’s only an entry level position but—”

“Whoa,” Amber said. “I haven’t been getting any messages.”

“I’ve left you five! They want someone to start as soon as possible. They’ve already begun interviewing.”

“But it’s in Naples? I have a lease here.”

Lucy scoffed on the other end. “Wasn’t the whole point of that hellhole to save money only till you found a job in your field?” She suddenly sounded very far away, like she was speaking at the end of a very long tunnel. “What’s that noise?”

“I’m not sure,” Amber said. “Interference?”

“Get a cell phone already,” said Lucy. “And don’t forget to send your résumé!”

Then Amber was alone on the line. “It’s not a hellhole,” she said to no one.

The next day, still unsettled by Ed’s absence, Amber decided to pay Mandelbaum a visit, as calling her was impossible. From their written correspondence Amber had her address, and after she dug the envelope from beneath a pile of junk mail, she made the drive on one of her rare days off. Mandelbaum lived at the end of a quiet street in a house almost completely hidden by overgrown palms. As Amber rang the doorbell, she smelled rain in the air and hoped she wouldn’t be caught in it.

A woman answered the door after a few moments, tall and thin. It took her a minute to realize this was, in fact, Mandelbaum. She wore all black as she did that day in July when they met, the same long skirt and turtleneck. She’d been thin before, too, but in a brittle way, whereas now it was more a healthy slender. She smiled at Amber, but her eyes glinted with something else. “Won’t you come in?”

As Amber stepped inside, she was taken aback by how cold it was. So she did use AC after all. As her father would say, Cold enough to freeze the balls off a brass monkey. So when she offered tea, Amber eagerly accepted. The woman’s surroundings were austere, with minimum decorations, none of the tchotchkes Amber—perhaps ageistly—expected from a woman her age. She wanted to ease into the conversation regarding Ed, though unsure why exactly so, as Mandelbaum rummaged around in the kitchen, Amber informed her about the issues she’d had with her landline. Rain began to tap against the windows, then pound.

“And you don’t have a cell phone?” she called from the kitchen.

“Ha. No. Been holding out I guess.”

Mandelbaum entered the living room with a tray, and on it the kettle and two tea settings. “You know what they say, adapt or perish.”

“Yeah, I guess.” An interesting remark, coming from someone who didn’t even appear to have a landline herself, Amber thought. “Anyway,” she continued, hot tea flooding her mouth before she realized she’d even drew the cup to her mouth, “if someone could come by and fix it, I’d appreciate it. I don’t know if the problem’s electrical or what, so I figured you might know what to do or who to call—er, contact. But the main reason I came over was to ask you about my neighbor. Ed.”

Mandelbaum’s eyes flashed, then she smiled. “You know, you remind me of myself when I was young.”

Amber blinked, asked plainly, “What happened to Ed?”

Mandelbaum paused, the teacup in front of her lips. “The tenant who lived below you? He moved out.” Amber stared as she placed the teacup back onto the saucer with a light tink!

“Huh. It’s just I never saw him move out. Do you know if he’s ok?”

“I’m sure he’s fine. He left the place in good condition, and that’s the only business I really care to stick my nose into.”

Amber let her own tea grow cold. She didn’t know what she expected to learn by coming here, exactly, but it didn’t escape her that not once during the visit did the old woman’s hands shake.

(November)

Amber had become obsessed with the mirror in her house, losing hours in front of it, deep in thought, tracing the vine-and-leaves frame with her fingers, the metal cool under her skin. She tried everything to keep it in good condition, but the glass continued to spot till she could no longer see herself clearly. Today, she stood in front of it in the clothes she bought for her interview, barely making herself out, waiting for the excitement to hit. Lucy had scheduled the interview on her behalf, as Amber’s phone still didn’t work. Mandelbaum had said she’d send someone out to look at it, but either she never did or else they just never came. It hardly mattered to Amber. Nothing mattered to her much these days. Even the interview, scheduled for the next day, felt far away, and she struggled to remember the reason she wanted to go into journalism in the first place—a “dying career” as she’d heard over and over again. She had always doubted the significance of her own words, prioritizing those of others instead.

Sighing, she stripped out of the interview clothes and draped them carefully over a chair for the morning, then changed into pajamas, set her alarm and crawled into bed.

She slept heavy and dreamt hard. She dreamed of waking up the next morning in time for the interview, despite the alarm never going off. She gets dressed and ready to leave. Everything simultaneously makes sense and doesn’t. When she can’t find the front door, she remembers that it moved some time ago but couldn’t, for the life of her, remember where. As she climbs back upstairs to search for it, she’s felled by a piercing pain. On her thigh a large gash stretches nearly to her knee. It bleeds splintered wood.

Eventually she woke to the sound of the doorknob turning. Somehow she was no longer in bed, but on the sofa, a blanket over her.

“Amber?” Lucy called as her heels clacked a hesitant rhythm toward the window.

That’s right, she reminded herself. She’d given Lucy a copy of the key in case she was ever locked out. She always prepared for the worst.

“What,” Amber said, voice weighted with sleep.

Lucy pulled a curtain and light came blinding in. “What are you doing?” she asked, her voice soft. “You never came in for the interview. An opportunity comes and you just let it pass?”

Amber rubbed her eyes. “What day is it?”

Lucy frowned. “You know you can talk to me, right? I mean, I’m here for you.”

Amber groaned. She didn’t have the energy to discuss such things.

“Sorry, it’s just…I remember finals a few years ago, when you were going through some stuff.”

Lucy was the only one who knew about the stint in therapy. Amber’s therapist had been bright-eyed, bubbly, and only a few years older than herself, the last a resemblance that promised compatibility, but instead only served to highlight their differences. Not that Amber hadn’t tried. In as early as the first session, she confessed her guilt about her father paying for her education with the pay from two jobs—both arguably worse than her current one. The therapist responded that the interesting thing about guilt was that it activated the brain’s reward centers; to feel guilt was only for your own benefit. She let this fact stand like a profound truth. What the hell was she supposed to do with that?

Another groan, this time from the house itself.

“What was that?”

“Pipes,” Amber said, not moving. She had resituated under her blanket, head nestled on a pillow.

Lucy gazed around at the ceiling. “I’ve never heard pipes like that. Her eyes got big as Amber pulled the blanket tighter around herself. “You’ve lost weight!” she said, staring. “Have you seen yourself lately? You don’t look so good!”

“Real nice.”

“I think you need to get out of here. I mean, move out. I don’t think living here is good for you.” She hesitated, glancing out the window. “I called your mom.”

That got her attention. “What! Lucy, no! Why would you do that?”

“When’s the last time you even spoke to her? She said she’s been calling you and you never return her calls. I told her I know the feeling.”

“Just leave me alone,” Amber said.

“She wanted me to come check on you,” Lucy said, standing up. Her shoes click-clacked to the door. “I’m going to tell her she needs to come down here.”

When the door closed and footsteps echoed down the staircase, she closed her eyes once more.

(December)

Almost late for her shift, Amber ran across the parking lot, smock balled in one hand, as the crows flew out of her way. It was getting more difficult to wake up; lately all she wanted to do was sleep. She waved to Carl, who pushed a large line of carts through the doors. When he didn’t smile, or even acknowledge her, she wondered what was wrong, as he was normally very friendly.

She punched in and looked for Gayle to give her a till. Amber saw her near the customer service center, asked which register she was assigned. Gayle said nothing. She didn’t even look in her direction.

Jackie, one of the morning cashiers, asked from her post if she could go on break. “You can go when Amber gets here.”

“Hello!” Amber said. “I am here.”

“She isn’t here yet?” Jackie asked. “Son of a bitch.”

After a few moments, Gayle said, “You know what? Go ahead and take your break. If it gets busy, I’ll hop on a register.”

Amber waved her arms before them, in desperation she shook Gayle’s shoulder.

Gayle scanned the space where Amber stood, her gaze traveling through her, unseeing.

As she backed away, an overcoming ache to be home hit her deep in the bones. Perhaps she was coming down with something. Homesickness, she mused. When the automatic doors didn’t open for her, she could no longer be surprised. It was like she didn’t exist at all. She waited for a customer to exit and followed him out.

Back home, she curled up on the sofa. She no longer searched for jobs when she got home from work. Ever since the missed interview it seemed pointless. Any job would eventually turn into one she didn’t want anyway. And what felt more luxurious than this: being bundled up on her sofa at noon on a Wednesday, with nowhere to go, nowhere to be? She could just be right where she was. She had all the time in the world to just be.

Amber let herself sink farther into the sofa cushions. It was only noon and she had only woken up a few hours ago, but she let herself drift off anyway. She sunk deeper into the sofa and then felt herself sink even deeper than that, into the floorboards, into the ceiling and walls of the unit below. The particles that made her up dissolved and mingled with the particles that made up the house.

She didn’t know how long she dozed but she woke to the sound of people climbing the staircase to her door. She heard a low creak and knew it was the third step from the top. She knew this place intimately now. She felt it in her bones.

“You have neighbors below you,” she heard old Mandelbaum saying—who wasn’t old at all anymore—“but I don’t think they’ll be bothering you. They’re very quiet.”

There was a young woman with her, maybe just a couple years older than Amber. Mandelbaum stood tall now and wore her shimmery gray hair in thick waves down her back. There was a pink glow to her cheeks, and an effervescence to her voice that wasn’t there before.

Didn’t they see all her stuff? she wondered. Or had that disappeared as well? When she looked in the mirror, which had returned to its former luster, only the north wall of the bedroom stared back at her. She didn’t feel as if she were even looking out of her own eyes anymore. She could see from more advantageous angles, from every angle of the house in fact. It was as if she were watching them from the eyes of the house itself, from its walls, its windows, its floors.

This wasn’t worrisome. On the contrary, she’d never felt more at home in her life. There were other presences here too, in the walls. Many others. Perhaps one was Mrs. Arenas, or Ed. She wasn’t alone and knew she never would be again.

Every so often, Mandelbaum caught Amber’s gaze and gave her a sly smile. It felt weird to be looked at. It was a long time since anyone had really seen her. She could sense Mandelbaum’s hunger and knew that before this young woman—by now Amber gathered her name as Heather—moved in, Mandelbaum would spend a couple days here, feeding on Amber’s essence like a baby bird from its mother.

And for the first time in days, Amber felt hungry too. She eyed the girl, Heather, and craved her energy. Only little by little, though, Mandelbaum’s eyes seemed to warn her, so that this new girl wouldn’t catch on.

Yes. It was important she didn’t get scared off. So Amber would devour her nice and slow, piece by piece, until every hope and every dream disappeared. There wouldn’t even be crumbs. Her stomach growled.

“What was that?” the girl-called-Heather asked.

“Oh, old houses make all kinds of noises. The pipes here make a racket.”And as Heather walked around, staring around the inside of the house, Amber’s insides, Amber found it funny—hysterical, really!—that this girl didn’t realize it, but she was already in her stomach, already consumed. She had only to be digested.