The Thief

Joseph Rakowski

I listened to my father beat on the heavy bag in the garage. When he was finished, he’d lie on the cement floor leaving behind this dark wet mark of his figure that I’d run my hands over. He did this for hours toward the end; beat on the bag like something was out there in the garage with him, hitting him back. The cracks and pops of the leather, and the noises he made like he was under attack by an enemy we all saw differently. I opened the door once to try to spot his opponent, and he stared at me like a great blue heron, his eyes made up of distant suns, his leather bag swinging from the ceiling like there were demons trapped in it and he was keeping them there with each punch.

My father’s battle shook the whole house. And I never opened the door again or watched him lie on the ground with his boxing gloves over his face crying into them. I just listened to him through the walls and watched as the picture frames rattled, turning sideways photos of our family. When he was finished, he’d come inside and sit on the couch and strip off his clothes until he was only in his boxers, sweat dripping down his back and his long hair soaked and stuck to his neck. My mother, with her deflated pregnant belly that still looked like it held a child, would get him a glass of water, and he’d sip it staring at the future that wasn’t there anymore.

He hadn’t been a violent man for some time, but it was always better when he was beating things in the garage. If he got his war out, he’d be less likely to hit something else, never me or my mother, not really. And my mother swore if he ever did, she’d outlive him, which was impossible, and when he died, she’d punch his bloated face as he lay helpless in his coffin, right in front of everyone, and run that clown makeup from his chin to his forehead like a car had run over his corpse.

Something about taking her beating with him to the afterlife made the color of our living-room walls lighten, made the blackness that grew up them soften until it vanished. He wasn’t angry at us, and when he did lose control, he yelled about things that couldn’t be changed. How he was so godawfully helpless. He worked hard to convince us that everything going wrong was somehow his fault.

When mother got sicker, I asked him to teach me how to throw a straight right, twisting my hips the way he did, fully extending with a snap. He wrapped my hands in his cloth wraps that were twice as long as I was, and then he showed me how to place my feet and keep my hands up: my right hand just off my chin and my left hand a little farther out in front of me, my body bladed to my opponent. He had me punch his palm as he directed the motion of my hips with his other hand until I said I was ready for the real thing.

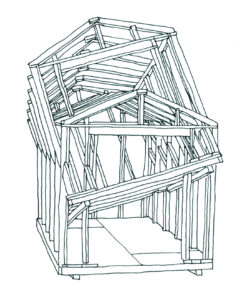

He put his boxing gloves on me, but they made my arms slow and sink, so he pulled them off. He took the gloves and put them on the handle-ends of a shovel and a rake and strapped them tight; then he stood behind the bag, one arm on each side, the gloves sticking out at me like spears. You have to close the distance. Learn how to get inside your opponent. Hit, he said.

The moment I loaded my fist to strike, he jabbed me in the face with the boxing glove attached to the end of the shovel, and down I went. He watched me roll around on the floor until eventually I got up and walked over to the door that led inside, a quitter. Though his expression showed he didn’t blame me for leaving, I could tell he knew I’d come to hate that part of myself if I didn’t kill it before too long. He didn’t say anything, just spit on the floor and let me go.

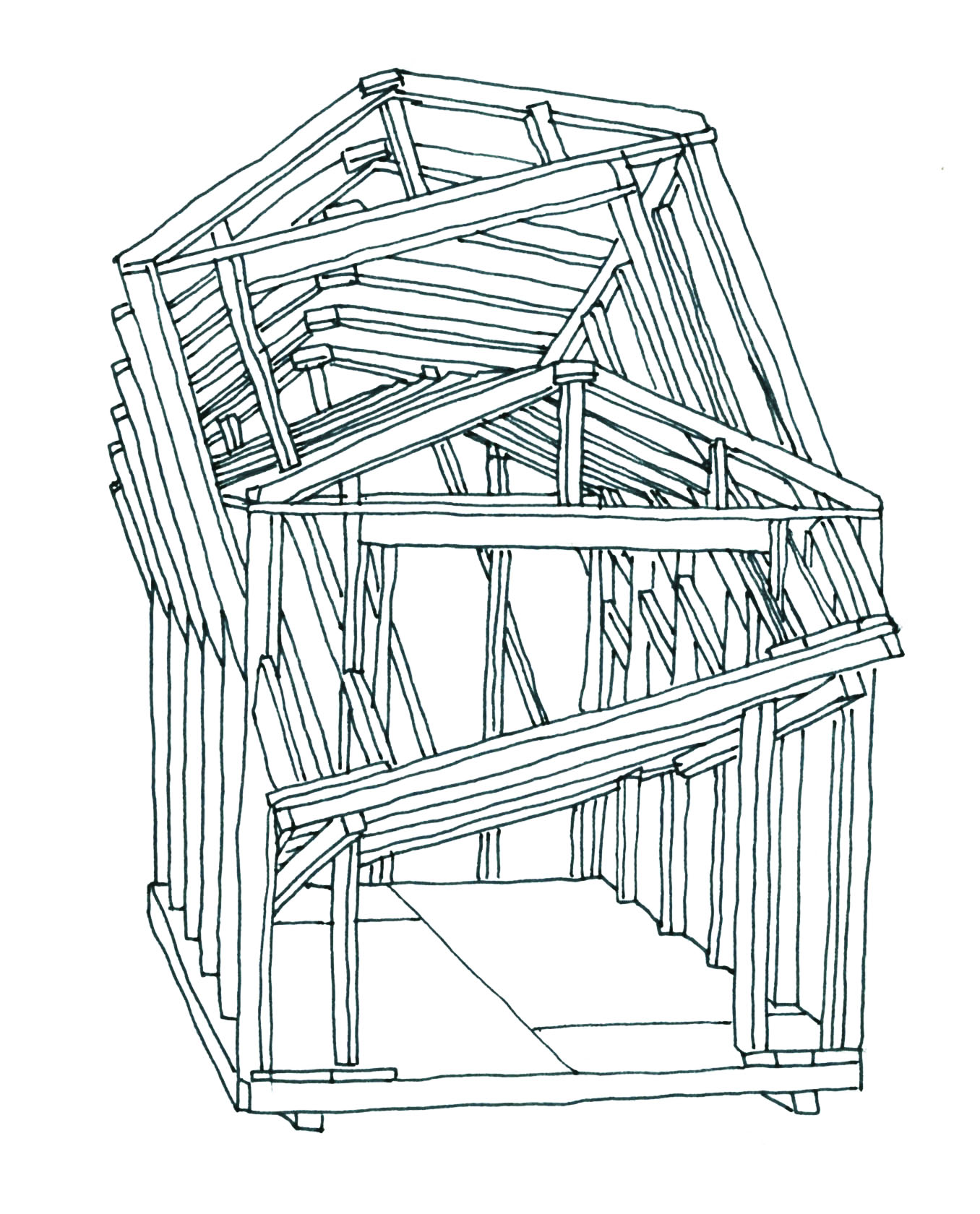

That night he came into my bedroom, took the cloth wraps off my chair, and left a small wooden turtle he’d carved on my desk. He’d been doing that lately, carving little wooden creatures. If he wasn’t beating things, he’d sit in the garage with his knife and scorp and take square blocks of basswood and turn them into little animals. He was terrible at it. The turtle he’d left me, I found out the following morning, was supposed to be a frog.

I took the frog to school and displayed it on the edge of my cubby, and when we came in from recess, it had been nicked. I ran to the teacher and told her what had happened, and she assured me no one had been into the classroom while we were gone. She said that I must be mistaken and to look for it when I got home.

“How the fuck could I be mistaken? It was right fucking there,” I said. And then I was in the chair in front of the principal’s office bawling my eyes out as they called my mother, who called my father, who was on his way from work.

He didn’t look at me as he exited the principal’s office, just gestured me to follow him with a roll of his shoulder. He didn’t say anything in the car, and I prayed at every stoplight that he wasn’t going reach under his seat for his kukri and snatch the life out of me. I don’t think he’d ever heard me cuss, and maybe he was as shocked as I was that those words had come out of my mouth so freely. He knew mother didn’t talk like that, and he had been careful not to go off if I was around to hear it. But he’d be surprised at what traveled through the wood beams of that house.

My father pulled the car into this little ice cream shop that we didn’t stop at anymore, and at first, I thought it was just an opportune parking lot for what was to befall me. It was cold out, not snowing cold, but it wasn’t ice cream weather, but he pulled right to the front of the shop and got out. We sat on the hood of the car eating ice cream cones and freezing our asses off, but he licked at the sides of his like he was strolling down some boardwalk on the beach.

I didn’t hear him come into my room that night, lulled to sleep by the rocking of our house, and when I awoke, a new carved animal was sitting on my desk. A horse, his best one yet, complete with a mane and the subtle contours of hooves.

I waited a week, but I eventually brought it to school and put it right where I’d put the frog. When we headed out for recess, I made sure I was the last one in line, and when no one was looking, I swiped it. On the playground, I found a good spot where no one ever went, and I buried it deep in the dirt.

I rose hell when we got back to the classroom. I accused a boy who was a jerk, but not the thief, and tipped over my desk and trashed the cubby wall until I was sitting in front of the principal’s office again, crying my eyes out.

I could hear my father yelling in there this time, and I racked my brain to confirm no one had witnessed my heist, that there was no way this could be traced back to me. And I was right. There we were again, the same ice cream shop, two cones, and we sat on the hood together watching the passing traffic like it was a 4th of July parade.

It was shortly after this when my mother became really sick, and in between hospital visits, she remained in bed. She shrank every day. That’s what happens when you start dying, you start shrinking. Every day you get a little smaller. Your bones appear, stretching through your skin like they’ll tear through if you move the wrong way. Your hair shrinks, the color in your skin shrinks, the light in your eyes shrinks, and finally your voice shrinks, and then you’re being carried, your body as light as a rolled bedsheet, to the bathroom and outside for fresh air that only makes you nauseous, but you sure wanted to see the evening sky again.

My father stopped shaking the house when my mother told him the vibrations made her ache worse and sent a crackling down her bones like he was turning them into dust. He removed the bag from the ceiling and installed a metal stand that he bolted into the concrete, and now all you could hear was the sound of the leather and his hollering, the same hollering that I mimicked the next time I was in front of the principal’s office.

This was the second time I’d stolen my carved animal. This time it was a lion or a panther, some sort of big cat, I think, not as convincing and detailed as the horse. I’d planted it in a boy’s backpack, the one I’d accused last time. When he went to calling me a liar, I threw the straight right like the boxing-glove-wrapped-shovel, and down he went. He was sitting in the chair across from me as we waited for our parents to exit the principal’s office. His mother and father had both come to the school. His mother was beautiful, and she spoke to us softly that the parents would sort this out and that there was no need for fighting, not now, not ever.

Her son was still crying when they came out of the office, and I could never figure how he’d managed to muster up the racket up for so long when he knew he’d be fine. I didn’t feel bad for him. Someone had stolen the frog the first time, and innocent or not, someone had to hold the bag for it. This kid, with his perfect mom, had enough on his scale to even things out.

My father handed me back the wooden cat, and this time we didn’t stop for ice cream. I leaned toward the window like I was expecting him to turn into the shop, but he drove straight past it. The parking lot was empty, and there wasn’t a line out front. I slouched in my seat, and he told me to sit up straight or walk. I was half tempted to say walk. But I knew there was no way he was letting me out of his car, so I stayed quiet and shifted myself up, the taste of chocolate-vanilla swirl missing from my tongue.

When we got home, my father didn’t get out of the car. As I went to undo my seatbelt, he told me not to mention a word of this to my mother. When he caught me skipping school to lie next to her bed, he acted like he didn’t notice. When she slept, I cut a trail through the woods behind our house. The trees were bare now, and light took on the form of their long naked extremities. I refused to wear a jacket, and with the trail and my bike, I had a path that led to my old school where I spied on my classmates with my binoculars. I watched them run on the snow-covered playground, and I could hear their laughter in the thin air. I wanted to dance again on the white fields with them.

My father only wailed on the bag now and stopped carving animals for me even though I left him blocks of wood under his drying boxing gloves. He just lay on the garage floor until the concrete made his body shake with chill and froze his shape. I took one of his old pocketknives, and as I walked through the woods, I shaved off pieces of his last stupid cat sculpture until there was nothing left of it. Sometimes returning home through the tree line, I’d catch my father kneeling along the side of the house. Both hands gripped together and trembling toward the thin gray heavens like his insides were being pounded by jabs and hooks.

There were cars and an ambulance out front when it happened, and I stayed in the woods until I lost the rotten smell that attaches itself to those who have lived around the dying. On the day of the funeral, I ran through the woods and climbed the fence to the playground and dug up the horse that had been buried there for months. The dirt was cold, and the horse had taken on a dim stain the color of the soil. I brushed it off and felt the wood come alive again as it warmed in my hands, its heat fully returning in my breast pocket as I stood viewing her. And I know now the last thing to shrink when you die is the memory of you, but that soon fades too, and then there are only rumors of what happened. Then those are gone too, and all is forgotten, shrunk, and entombed.

My father watched me place his carved horse under my mom’s folded hands, and he knew what I had done. I wanted to crawl in next to her and have him bury us both, but my father closed the lid and threw the first handful of dirt back into the earth. I thought about us digging her up and holding her in our hands until the warmth returned to her, but that was a long time ago.