Dream of a Unified Field

Josh Emmons

Alice Powell gave her candidacy registration form to the city clerk and tweeted that she was running for mayor, and then she emailed a press release to the Ambleside Register. “Oh joy,” the editor wrote back. Fuck her. The Register was mostly ads for second-hand outriggers and bankruptcy lawyers these days, and Alice would ignore it after she won.

Coming out of the town hall building, she decided to skip a two o’clock open house for a property that wouldn’t sell, and instead work on her candidate mission statement. Although no one else would run, it was important that she put something sweeping and bold on her campaign site, and later that night she and her wife, Naomi, would lie on the couch and do some nitrous oxide while listening to an old Esalen Institute talk, Joseph Campbell on Om or Michael Murphy on the Human Potential Movement.

A couple of kids in ripped jeans whizzed past her on kick scooters and a half-empty transport truck groaned by, trailing a line of oil on the street.

Ambleside might be a dying mining town, but soon it would be her dying mining town, and she’d bring it back to life with a slew of strong remedies: free parking downtown, tax incentives for relocating factories, a spaceport contract for Mariner Island, relaxed liquor laws, refugee resettlement housing, a sister city deal with Helsinki or Pusan—the list would go on.

“Hey Al, you seen Karisma?”

Alice looked to her left and saw her friend Belinda idling in a gray sedan at the curb. “She lose her phone?”

“Yeah, right.” Belinda looked tired and peri-menopausal, like everyone these days. “Her boss at Save Rite called and said she’s supposed to be at work right now, and if she misses another shift he’s gonna fire her. It’s bullshit what she’s doing, and it’s unsustainable.” She sneezed violently. “Did you know you can legally kick your kid out once they’re eighteen?”

“Yep.”

“The question is how do you do it? How do you get that strong on the inside?” Belinda looked at Alice searchingly. “It’s in her best interest. It is. It’s the only way she’ll learn responsibility and how she actually has to do what she says she’s going to do in this world.”

Alice had moved out of her parents’ house at sixteen into a shelter that didn’t make reconciling with them a top priority. There she felt an almost cosmic sense of freedom for the first and maybe last time in her life. “If I see Karisma,” she said, “I’ll tell her you’re looking for her.”

Belinda gave her a thumbs-up and accelerated back onto the street.

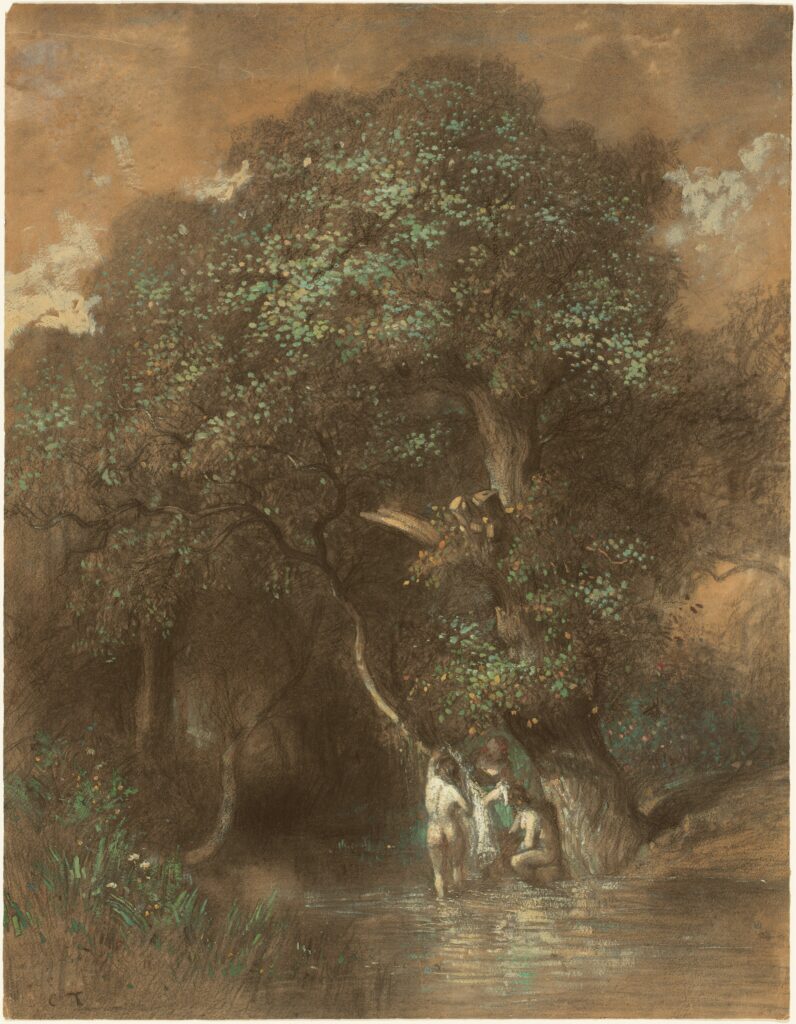

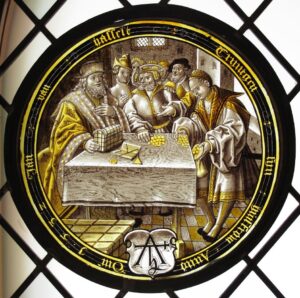

A flock of Canadian geese flew in airshow formation overhead, the sun behind them ringed by a halo of solar dust, and Alice walked downtown to get coffee. Her great-grandfather, Monty, had been in politics, an alderman in Chicago, serving just after Prohibition, when gangsters and cattle barons ruled the city. By the time Alice was a kid in the eighties he was living on a generous pension plan and advising her to go into politics someday. “Get the top post in a small town,” he told her one afternoon at McDonald’s, the sunspots on his forehead forming a blurry constellation. “Become mayor.” A small bag of fries sat on the table between them. She’d inherited her best features from Monty, sea green eyes and a dimpled chin, and modeled her outfits—wool slacks, fitted sports coat, homburg hat—on his. Holding a ketchupped fry like a cigarette between his fingers, he said, “As mayor you’ll be able to get things done and ignore the special interests. Jesus Christ, stay away from the special interests. You know about the hedgehog and the fox, right? You’re twelve now. No? There are two types of people in the world, hedgehogs and foxes.” They were sitting on hard plastic chairs that didn’t swivel, and the orange on orange of their surroundings gave Alice a spacey feeling. Monty wetted his napkin in a cup of water to spot-clean a ketchup spill on his slacks. She watched in fascination as flecks of napkin got stuck in the herringbone fabric and became more noticeable than the spill. “Those are the types,” he said. Alice had just come out to herself after an electrifying sleepover with her best friend, Susie Tritt, during which they’d talked about nipple sensitivity and why a band called the Slits was called the Slits, and how in every conversation they’d overheard between women talking about sex with men, one or more said they never orgasmed. Still, she wanted to know what Monty meant about hedgehogs and foxes, feeling an almost painful desire to please him. “What’s the difference?” she asked, slurping a strawberry milkshake through a flimsy straw. He looked at her for what felt like a long time, his neck an accordion of labial folds. She said, “Is it that hedgehogs see what’s under the surface since they live underground, and foxes see above the surface since they’re aboveground?” Monty clasped his bony hands over his knee while a teenager in a crinkled paper hat and brown rayon uniform mopped nearby, and said, “Hedgehogs have one big idea about the world and that’s all they see, whereas foxes see the whole picture. All of it. You can have another milkshake if you stop sucking on that one. You’re a good boy and I love you. Special interests are full of hedgehogs who only see school reform or the small business class, say, or neighborhood safety. They think their thing is more important than everyone else’s thing, and they’ll give you good reasons. They’ll be convincing. You’ve got to ignore them or you won’t see the big picture, and the big picture is the truth, and that’s the greatest good for the greatest number of people. George Washington became a hedgehog at the end of his life when he got obsessed with canals. All that mattered was canals, he thought. Someone who is the first president of a country, they should see the dangers of hedgehog thinking clearly, and they should be foxy.” Alice got that second milkshake and imagined touching Susie Tritt’s nipples (“Tritt’s tits,” she whispered under her breath) and told Monty that when she went into politics it would be as a fox, and she would get the top post. Monty repeated that she was a good boy, the best boy, and promised to leave her his box of alderman mementoes when he died. She later hung up his commemorative public service plaque in her college dorm room, then in the studio walk-up she shared with someone best forgotten, then in a penthouse apartment with panoramic views of Lake Michigan and the north shore—what a way to live, skybound—and now in the den of her Ambleside home, beside the only erotica Naomi had ever painted, a Sumerian bathing scene of women grooming each other at a desert oasis, their skin silvered by moonlight. This commemorates Montgomery Zagayevski’s eleven years of public service to the city of Chicago….

Coming to Fairgrounds Coffeeshop, Alice saw Naomi sitting at an outdoor table under a shade umbrella with Kyle Robeson. She paused before approaching them. Kyle had long silky black hair and was too good-looking and always needled Alice for not seeing the plays his repertory theater staged inside an old, drafty Congregationalist church that smelled like ammonia. Happily, the theater was about to close, and he was rumored to be moving away.

“What’re you doing here, sugar?” Alice leaned down to kiss Naomi and waved for Kyle not to get up. The table had soggy scone crumbs on it and a detailed sketch of a thin penis at its center. “I thought you were in the studio all day.”

“I’m on a break.” Naomi twisted a dry lemon wedge over her tea. She’d dyed her half-inch Afro red the day before, and pink spots bloomed on the back of her neck. “Kyle’s got news.”

“I heard about the theater closing, Kyle,” Alice said. “What a blow to the community.” That sounded snarkier than she’d meant it to. “And you’re moving to Phoenix, right?”

“He’s not moving to Phoenix,” Naomi said.

“No?”

Kyle took a sip of coffee that dribbled onto his beard and shirt. “I was just saying,”—Monty would’ve spot-cleaned the coffee spills right away— “that I hope it doesn’t get weird between me and you because may the best person win.”

“Win what?” Alice said.

“I’m going to run for mayor.”

“You are?” She stepped back from the table. “You are? But you’ve never come to a city council meeting before. Never. And you don’t support or oppose anything. You don’t know how procedures work or measures are passed. You have no civic mission.” To Naomi: “Is he joking?”

Naomi tilted her head the way she did when uncertain whether to be truthful or diplomatic. “I don’t think so.”

“I’m not running against you,” said Kyle, pulling his silky hair into a sleek ponytail. “I’m running for Ambleside.”

“How’s that?”

“I’ve got a plan to fix the town’s finances.”

Alice had once thought about Kyle while Naomi’s head bobbed between her legs, an electrifying memory that didn’t really matter. “You want to be mayor with no experience? I’ve been on the council for six years and before that I attended public forums. I organized public forums. I canvassed for candidates at all levels of government, I collected signatures to pass ballot amendments. But you’ve got a plan to fix the town’s finances. What is it? What’s your plan?”

Kyle squinted as if reading a far-off sign. “I want to build an eco-park on Mariner Island that’ll bring green tourism to the area.”

“A park?”

“An eco-park.”

Naomi sipped her tea. “He’s got in mind a refuge for endangered animals and plants that’ll offer a safari experience for Americans from all over the country, and even the international market.”

“How glorious,” Alice said.

Kyle set his coffee cup down on top of the penis etching. “I was just asking Naomi to design a few signs and promo images for my campaign, but I told her to say no if it’d bother you.”

“Good, she says no.”

Naomi looked up at Alice. “And I told him you wouldn’t have a problem with it because I need the job and you’re confident in your own candidacy.”

Everything around Alice—Naomi, Kyle, the hidden penis, the sandwich board propped up on the sidewalk advertising a meatloaf sub and chunky potato salad, the cut-out clouds above and the haloed sun and the prideful Canadian geese—throbbed with pre-migraine light. She walked away from the table slowly, and at the end of the block heard the clacking of Naomi’s bracelets behind her.

“Hey, sugar,” Naomi said.

“I’m not your sugar.”

“You are my sugar, though you were rude to Kyle. Who I know you’re surprised he’s running, but he’ll give me $7,000 for a couple of designs that’d pay for my studio for a year and some of my treatments, and we could get the roof fixed, and it’d be a windfall for us. You need to come back and apologize to him.”

Alice turned around. “And you need to support me. I can’t believe I even have to say it. I announce today and you decide to help Kyle?”

Naomi crossed her arms and shifted her weight from one leg to the other. “I do support you. I supported you through two city council races and I support you now. Kyle’s not going to win, you know that. He’s just running because the theater’s closing and he needs something to do, whereas you’re Ms. Ordinances and Ms. Measures, and you’ve got this.”

Alice looked at the woman she loved, at the gold hoop earrings hanging halfway down her beautiful brown neck, at a loosely hanging shawl she’d given her on their tenth anniversary, and six months after Alice’s talk with Monty at McDonald’s, he quoted Ecclesiastes to her: “I returned, and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favor to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.” They were standing by the Chicago River, which had been dyed an emerald green for St. Patrick’s Day, and Alice no longer saw Susie Tritt, the drift of time and timidity having pulled them apart. Five weeks later Monty died from lung cancer. During the funeral service she rubbed a swatch of his herringbone slacks between her thumb and forefinger, and at the reception her mother told her she could no longer wear suits and homburgs like his. “It was a phase you went through,” her mother said, wiping tears from her eyes, “and now it’s over.”

Alice kept staring at Naomi’s shawl and didn’t say anything. Then Naomi turned and walked back to Fairgrounds as another empty flatbed truck cruised by that in the past would’ve carried four or five tons of iron ore to cargo ships docked on the lake. Alice noticed Belinda’s gray sedan parked across the street, went over to it, and got in the passenger side. A show about gardening in a northern climate was playing on the radio.

Belinda looked straight ahead, her hands resting lightly on the bottom of the steering wheel. “Remember when Karisma came in third at the eighth-grade state spelling bee, and she wore the same sweater vest for months and worshipped that Harry Potter girl?”

“No.”

“Now she’s got neck tattoos and the earlobe plugs, and her boyfriend doesn’t have a last name.”

The radio show was recommending the best brand of electric garden blanket to thaw frozen soil for planting in early spring, a miraculous device that turned permafrost into paradise. Alice placed her hand on Belinda’s, and when Naomi had been diagnosed with fibromyalgia two years earlier, she’d cried with relief. Her wife’s mysterious pains and dizziness and nausea weren’t cancer related. The symptoms didn’t foretell the end of the world. Alice and Naomi drove straight home from the doctor’s office and made love without the specter of death hovering over them. Then they did nitrous oxide and listened to a talk about how Gestalt Practice facilitated intrapsychic dialogue between the various parts of the self, allowing for inner cohesion. “Maybe we should try that,” Alice said when the talk ended, feeling as spacey as she had with Monty, the only person in her family who hadn’t thought something was profoundly wrong with her, the only person in the world who had believed, against the outward signs, that she was the best boy. Naomi sat up groggily and slid on a t-shirt and said, “I like having different voices in my head with different points and perspectives. Thirteen ways of looking at a blackbird.” Alice felt a headache coming on, and Naomi kissed her cheek and said, “Monty’s idea that everybody should be a fox, maybe that’s a kind of hedgehog thinking in itself.”

When the radio show took a commercial break, Alice said to Belinda, “Don’t kick Karisma out when she turns eighteen. That might teach her responsibility, but it’ll fuck up your relationship with her forever.”

She got out of the car and went back to Fairgrounds, where Kyle and Naomi were looking at fonts and color swatches on a tablet.

“I’m sorry, Kyle,” she said. “If you win, I’ll support you.”

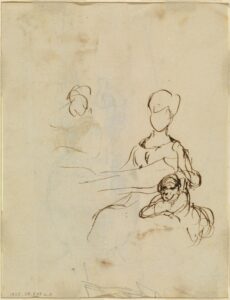

Kyle gave her an ingratiating smile she wanted both to get lost in and to wipe off his face with sandpaper. Naomi took a graphite pencil from her bag and began turning the penis drawing on the table into a fire hydrant.

“Good luck with the design,” Alice said to Naomi. “I’m off to an open house but should be home around five, if you want to start early on the couch.”

Without lifting her head, though with a hiccup of pleasure in her voice, Naomi said, “You’re going to the open house that won’t sell?”

“Maybe it will,” Alice said. “What do I know?” and left before an answer occurred to her.