Not Everyone Gets To Go To Tennessee

Andrew Furman

We must have sat around the Grace Community Church parking lot beneath the bare-stripped oak and maple foliage for at least an hour freezing our butts off, my fellow scouts and me, just ten of us or so this morning (hardly the 100% participation our Scoutmaster insisted upon), slurping hot chocolate and eating donuts someone bought from the Dunkin’ that finally opened on Highway 1. Dr. Hargrove, our Scoutmaster, had this thing about us getting up super early even when it didn’t seem necessary and about not covering up our Class A’s with jackets during formal scout activities, which included canvassing for the spaghetti dinner. He and the rest of the adults were leaning up against Mr. Ackinclose’s big van, smoking cigarettes and drinking coffee out of behemoth travel mugs and talking about whatever adult men talked about. Mr. Ackinclose had that big van because he and his wife bred, sold, and showed French Bulldogs, all of which he claimed was very complicated. He was pretty old. His son had been in the troop like a gazillion years ago or something and now lived down in Portland. Meanwhile, Mr. Ackinclose continued to serve the troop all these years later in some vague supervisory capacity, sitting in on random boards of review in full uniform, kerchief and all (I hadn’t yet decided whether or not this was creepy), testing whether we could deploy a pencil and ruler to identify locations on a map according to the Universal Transverse Mercator system, whether we knew a bowline knot from a half-hitch, stuff like that. I found myself gazing over at the adults quite a bit this morning, when I wasn’t watching the chickadees looping in and out of the big hemlock next to them, mostly because my fellow scouts were going on and on about Overwatch, which I didn’t play. I still played Minecraft, which I knew enough not to disclose.

When it was finally time to go, I was assigned to Dr. Hargrove’s truck along with a few of the older Trailblazers, probably because Dr. Hargrove had figured out by now that I lacked motivation when it came to fundraising, or really anything scout-related, and needed the older scouts to ride herd on me since not everyone would get to go to Tennessee. This was my second season canvassing to earn my share to fund my troop’s annual summer trip that “not everyone” got to go on. (We went to Utah the year before, which was hot as balls.) Six straight weekends leading up to the spaghetti dinner we piled into the cars and trucks of volunteer dads, flouting seatbelt laws half the time to hit up neighborhood homes and storefronts far away as Machias. There was a group Facebook page open only to troop leaders and other parents to coordinate or whatever. I imagined that they used the page primarily to come up with persuasive phrases like not everyone gets to go to Tennessee to get us to do stuff we weren’t keen on doing.

Dr. Hargrove’s truck smelled like fish and stale tobacco this morning and it took some effort not to squinch up my nose riding in the second row between Griff and Connor, Dr. Hargrove’s son. Connor called this “riding tampon,” a phrase I might have understood but didn’t want to think about too much. It was even more wicked cold inside the truck than outside with the wind whipping back through Dr. Hargrove’s window. He kept it open so he could stick his cigarette out there time to time to shed the ash and smoke. I didn’t understand how he could be a doctor but smoke stinky cigarettes one right after the other anytime we were outdoors, or almost outdoors like now. Creases tore across his narrow face in places you wouldn’t expect, maybe from the cigarettes.

“All right, hit it boys, and remember your script,” he said after parking along Pleasant Road’s cinder berm just off the highway. The crunch of the parking brake beneath his strong foot punctuated his command. Connor exited the tall truck ahead of me, gripping the doorframe with one hand, the back of the seat with the other, then launching himself out as if he were parachuting out of a military airplane, which is what he’d be doing in a few short years. “Let’s go Pukey-Lukey,” he said in mid-launch. He made no effort to hide his favorite nickname for me from his father—some combination of homesickness, fatigue, and lukewarm beanie-weenies had made me vomit across the sweet-fern groundcover in the middle of our hike last fall at Baxter State Park—maybe because there was at least a modicum of affection floating somewhere inside the taunt. Connor, in truth, wasn’t so bad.

I savored the oxygenating outside air, cold and spiced by the menthol of the big pines up and down this street, stuck “riding tampon” back of the smelly truck like I was. As he was SPL, Connor issued Griff, Dane, and me our marching orders as we stood on the dormant blonde grass of someone’s front yard. His facial hair, I noticed, was starting to look like an actual beard. Griff and Dane would take one side of the street and Connor and I would take the other. Although it seemed unsafe, and likely against Boy Scout rules—at the national if not local level—it was our custom to split up even further and leapfrog each other down the street, house to house. This way, we hit more homes and earned more money, not having to split the sales.

All the same, I wasn’t the best salesman, just old enough that I wasn’t as irrefutably adorable as the youngest scouts in the troop in Ospreys, nor quite old enough to be as savvy and even cutthroat as the Trailblazers, or maybe it was more about me than about my age. I tended to get hung up for too long at each house, listening to what these adults wanted to hear themselves say. It didn’t surprise me after only twenty minutes or so that I’d fallen behind Connor’s pace.

“Come on, pick it up, Lukey!” he called from two houses down the block, jabbing a finger at the house between us he wanted me to hit. “You want to go to Tennessee or not!?”

An answer wasn’t required and so I didn’t issue one as I skidded along the salt-studded asphalt, the county workers anticipating our first snow. Of course I wanted to go to Tennessee, he knew. We all wanted to go to Tennessee. Who wouldn’t want to go to Tennessee? Tennessee had more “bitchin’ caverns” than any other state, according to our SPL, and the plan was to visit at least four of the most bitchin’ ones, overnighting at various Boy Scout campgrounds and state parks along the way. They turn the lights off, Connor had said, and it’s like the darkest dark you can imagine. Even so, I wasn’t totally revved about the trip. I didn’t quite get the whole cavern thing. The dark still scared me some. This might have been one of the reasons Mom insisted last year that I join scouts, because a male role model might help me to overcome such childish fears. It was another one of those phrases that popped up time to time at Thursday night troop meetings and (probably) on the parents-only Facebook page, an important thing that every boy needed in his life, a “male role model.”

I didn’t knock on her door until we were mostly done canvassing for the day. By this time, Dr. Hargrove had already gathered us back into his stinky truck and deposited us three separate times at sleepy warrens just off the highway on the outskirts of town, which weren’t so easy to tell from the “in-skirts.” Marshville Road, this narrow street was named, a finger of road through battered woods just five miles or so from my house that was entirely strange to me. It was one of the few things I appreciated about canvassing for the spaghetti dinner, exploring certain nearby streets I’d otherwise maybe go my whole lifetime without seeing. It was a marvel, really, how you could live and breathe day after day, month after month, year after year, so close to certain places you never knew existed.

Not that there was much to see. The sun, so promising hours ago, had hidden itself behind an impenetrable screen of gray. Beetle-blighted spruce and a few deciduous skeletons leaned over both sides of the still-black and fragrant coating of surprisingly new asphalt as if the trees hadn’t fully ceded this terrain to a human neighborhood. The houses themselves were half-hidden behind neglected shrubbery and desiccated machinery, terrestrial and nautical, much of it resting on cinderblocks. I could tell pretty much by Connor’s body language once we shuffled out of the truck that he didn’t have high hopes for this street. He and the other Trailblazers had been doing this for a while, so they all pretty much knew which neighborhoods and even specific streets and houses had the highest likelihood of a decent haul.

He was right about Marshville Road, of course. Even before knocking on one door, then the next, and the next, I knew I was doomed by the general dilapidation of the property—the paint blistering off the wood sides, or the cloudy birdfeeder I could tell hadn’t held seed in years, or the bleached signage for a defunct political campaign. Most people didn’t answer my knock, even though I could usually tell someone was home by the noises issued by a TV, someone’s footfalls, or the muffled glottals inside. I knew better than to knock harder. These were people who didn’t welcome news from the world, most of it being bad.

The road sort of wound about and then fell off into a shockingly steep downhill, which must have been treacherous to navigate up or down by car come sleet and snow. It was so steep that I sort of had no choice but to lope rather than walk, my sneakers slapping like applause against the asphalt before it finally leveled off and I could slow down. I gazed for a moment at the beige-colored house at the bottom, taking its measure before my approach. The individual shingles seemed to have merged into one solid mass of gray decorated with an archipelago of moss.

“Forget that house!” Connor called from up ahead. “That old bag never gives!”

I’m not sure why I didn’t listen to him. It might have been for the sheer pleasure of open defiance, or it might have been because I wanted to get a closer look at the moss up there on the roof, or at the tree looming over the roof that I could tell wasn’t quite a maple (red, sugar, or striped) and still held most of its bright red leaves. I didn’t yet know that it was one of the few sweetgum trees this far north and that it only grew here because the ground stayed wet and warm at the bottom of the hill, and because the woman who lived here had let it grow even though it was planted way too close to the house, or vice versa. There was no front walk to speak of—it might have been hidden beneath several seasons’ worth of damp, dropped foliage—so I sort of had to think for a second how to make my way to the shrunken front door. A squirrel barked at me from one of the sweetgum branches as I approached, as if to warn me about the brittle round seedpods scattered all about under the tree, one of which my sneaker rolled across, almost landing me on my butt before I reached the brick landing.

Barely discernible beneath the grime on an ancient straw mat was the word WELCOME, which made me chuckle a bit all things considered. I didn’t hesitate to knock, mainly because by this time on Marshville Road I didn’t expect anyone to answer. But someone did answer, which prompted a round of hiccups I struggled to control. First thing I noticed, even before she started speaking, was that she wore a quilted robe and was tall, much taller than me, and old, but not super-old, and that her short hair was a color I couldn’t name.

“Didn’t you see the sign?” she asked, rheumy eyes drifting toward the dented No Soliciting sign nailed to the beige siding.

“No,” I said, which was true. Hiccup. “Sorry.” Hiccup.

“Ayuh, go ahead, young man,” she said in a nicer voice, my hiccups maybe softening her up a bit. “You’ve come this far.” She folded quilted arms over her lean stomach.

My hiccups went away as I rattled off my script, all the while looking past her robe at the dim interior of the house. Here was another reason I didn’t hate canvassing, this opportunity to gain a glimpse into other people’s homes to see how they lived. It was amazing how much you could see in just a few moments, in just a few square feet of interior space. The house opened into a living room with overstuffed mint-colored furniture I could tell, somehow, she didn’t sit on very much. The walls were crowded with gold and wood frames advertising photographs and fewer paintings, none of which I could really see too well. There was an unpleasant odor, too, I was just beginning to pick up, probably from the cream-colored carpet at her slippered feet, contoured in a way I’d never before seen, like cauliflower heads. I found myself going on and on about the virtues of the spaghetti dinner, adding any number of persuasive nuggets from the script, maybe because she made no gesture to stop me. In the whole Downeast, ours was the biggest and longest-running Boy Scout spaghetti dinner, which may or may not have been true. It was our only fundraiser of the year, which supported all the troop’s activities, including our next summer trip to Tennessee, the state with the most caverns in the whole country. “Not everyone in the troop gets to go to Tennessee,” I even heard myself utter, “only the scouts who sell enough tickets.” Here, I could see her mouth twist into a different shape I wasn’t sure how to read. Her thin lips were so pale that it was difficult to determine where they were, exactly. She could order her spaghetti dinner to-go, too, I said next, because it seemed like a feature she might appreciate. Or she could just make a small donation. This last bit was Mr. Ackinclose’s advice for closing every sale, which often worked.

“Okay, okay,” she replied. “You win.” And then she did something I didn’t expect her to do at all. Not at all. She smiled, revealing surprisingly white and straight teeth inside those pale lips. “Just come in for a second while I find my checkbook, ayuh. You’ll catch your death out there in the cold.”

Now this was the number one thing we weren’t allowed to do during canvassing, actually the only thing we were expressly prohibited from doing, enter someone’s home. It was a safety thing. That’s what I was supposed to tell her while I kept my feet planted on the dingy mat. Yet I could hardly imagine that this old lady, who’d already retreated down a hall to what I imagined was her kitchen, constituted much of a threat. I scraped my sneakers against the mat and stepped inside.

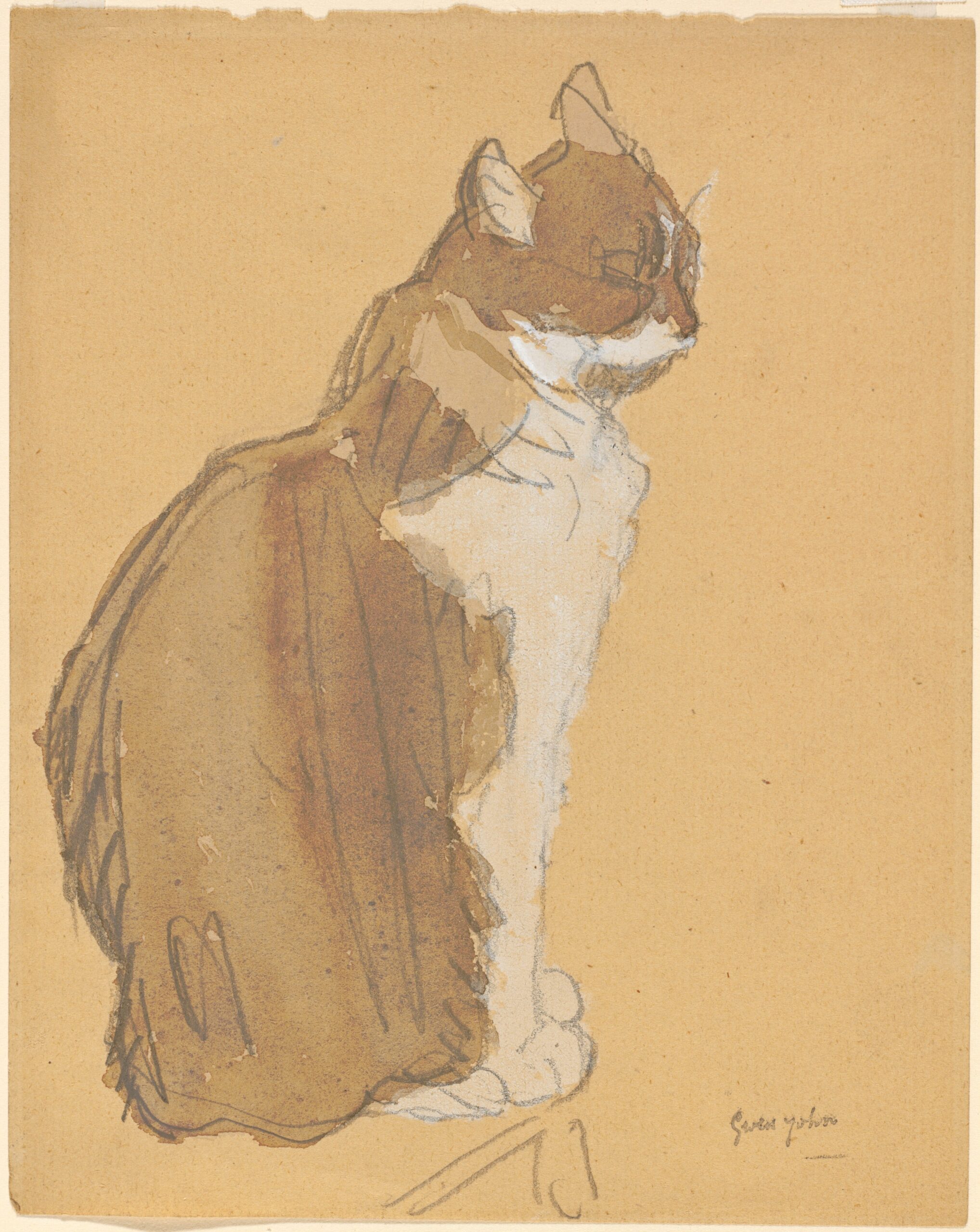

The inside smelled more strongly of that fetid odor, which I couldn’t quite place until a tabby cat poked its head out from a hallway door to inspect me, then retreated just as fast. I had just enough time before the lady returned to look at the various black-and-white photos floating inside the nearest frame. I could tell they’d been taken a long time ago because they had that yellowed look I didn’t know to call sepia. The photos were mostly close-ups of our granite coastline, foamy waves, trees, birds, and other nature-y stuff, one shot of a star-shaped leaf, maybe from that red tree outside, plus one photo of a man with a mustache, who might have been the lady’s husband, his shoulder-length hair parted in the middle.

“Now how much did you say the tickets were?” she asked upon her return, a thick pen braced between her fingers above the open checkbook, a pair of suede gloves drooping beneath. The question made me laugh a bit, even before I could wonder about the gloves, because it was the one part of the script, probably the most important part, which I had neglected to mention. I told her how much the tickets were, and she started scribbling something onto the check, the whites of her small knuckles flashing beneath her skin. She handed me the check ($20!) and let me inspect it for a half-beat before telling me that she only needed one ticket and that I could keep the rest as that small donation. I told her thanks, my eyes wide, at which point she asked whether I wouldn’t mind cleaning out the leaves from a very small section of her roof gutter before I left. Those gloves!

It might have irked me, her taking advantage of present circumstances, but it amused me, instead. At what point, I wondered, had she figured out that she was going to have me clean out her gutters—from the moment she heard the knock at the door and glimpsed me standing there in my Class A, or maybe at the point that she smiled after I’d given her the hard sell, or did it only occur to her that she might get some use out of me while she rifled around in the kitchen for her checkbook and came across the gloves?

She walked out the front door with me and led me around toward the side beneath the canopy of the fiery red tree for a while, and that’s when I found out what kind of tree it was.

“That’s a sweetgum clogging up my gutters and cracking the foundation in case you’re wondering. Outgrown its welcome but I just can’t see my way clear to upset it. Only sweetgum in the whole county.” I told her it was a pretty tree, those star-shaped leaves, that I’d never seen a tree hold such red leaves this late in fall, and that it was nice of her to let it be. There was a fairly new-looking aluminum ladder already propped against the beige siding and a much older five-gallon bucket next to it, the last remnants of blue words or some design clinging to its surface. It was a low roof so this wouldn’t be any big deal, I thought. I just had to be careful not to get my Class A dirty so Mom wouldn’t have to wash it. She handed me the gloves, stiff with someone else’s ancient sweat. I started scaling the ladder with the bucket. “Gilbert was going to do this for me,” she called from below, “but he probably shouldn’t be climbing ladders, anymore, and as long as you’re here.” She said the name, Gilbert, like he was someone I should know. Our backwater was the sort of place where you knew most of the people, or the important ones, anyway, the ones you could count on to come over and clean out your gutters.

I could tell that the lady was planning on standing there the whole time to watch me, which was okay. The soaked leaves clogging the gutter near the downspout were black with decay and the grimy runoff from the roof. They radiated a mushroomy odor as soon as I stirred them up, which wasn’t entirely unpleasant and definitely beat the ammoniac odors of the house. The mossy patches on the roof should probably be scraped off too, it occurred to me, but I wasn’t about to take that on now. I worked slowly so as not to drip the sludge all over my uniform while I transferred the leaves to the bucket. Before long, I had to descend to shift the ladder over a few feet and empty the bucket, at which point she told me that her name was Susan, which seemed like too young a name for her and which might have froze the look on my face, because she followed up right away by saying, “Mrs. Potter,” realizing that it would be easier for me to think of her as Mrs. Potter, or Mrs. Anything, than Susan. I told her my name just before scaling the ladder again and she just nodded, like I was used to people nodding after hearing my full name, as if they might have known someone in my family but weren’t quite sure. We were never very important around here.

“Frank still running things with the troop?” she called up after me.

“Frank?” I asked—finally staining my shirt as I knew I would—and then she clarified by saying Mr. Ackinclose. Funny, soon as she said that name, she seemed more real to me. She wasn’t just a tall old lady with a smelly cat, but an actual person in the world, my world, a person who knew Mr. and Mrs. Ackinclose for more years probably than I was alive and surely thought this or that about them. I told her yes, that Mr. Ackinclose was still with the troop, not bothering to clarify his exact role, which I couldn’t have done, anyway.

“He’s not so bad,” she said just as I descended the ladder again to move it over a few more feet. It seemed like a funny thing for her to say. I waited for her to say something else about Mr. Ackinclose, or to ask me to tell him hello for her or something as I climbed the ladder once more. But she didn’t seem to have anything more to say, so I just carried on faster now, my shirt already soiled. It was time for me to be on my way. Connor, Griff, and Dane, I noticed, were standing middle of the road staring at me, maybe weighing how much longer they’d wait before intervening. I think Mrs. Potter could tell by my more erratic movements that I was growing antsy to leave, because she warned me to be careful, and then she said one more thing before I even started heading down the ladder for the last time.

“Other chores you can do later, ayuh, you want to earn a few extra dollars.”

Mom texted me that afternoon to let me know she’d be coming home early, the diner being dead, so I should have known better than to be on my computer when she arrived. This invariably set her to hollering up the stairs.

“Darnit, Luke, would you get off your computer and come eat this pizza with me before it gets cold?!”

She worried over how much time I spent online when I wasn’t at school or scouts, taking advantage of the Clarks’ Wi-Fi other side of the wall. Worried, too, that I was watching stuff I shouldn’t be watching, naked people smashing and whatnot. My “male role models” warned our troop about this sort of thing all the time, not realizing that they were mostly revealing their own predilections, not ours. Mom needn’t have worried. When I wasn’t playing Minecraft this fall, I was mostly watching a YouTube channel that documented the round-the-world sailing adventures of a couple from New Zealand and their two young children. Most ten-minute episodes featured warm azure seas, colorful fish, semi-perilous mishaps on the boat, and strange human accents. The islands the family visited sported French-sounding names and seemed a fair bit more thrilling to me than Tennessee. I wondered if I’d ever get to go to such sun-lathered places as Montserrat or Curaçao.

Mom, smelling from Teddy’s like something fried, asked over our pizza how the canvassing went, and I told her pretty good, that I made almost sixty dollars today. “Over ten dollars an hour,” she said, raising her fair eyebrows above her pepperoni slice. “More than most hourly workers get around here.” She and some of the other parents dispensed this essential encouragement to us often, which they probably came up with on their Facebook page. I was about to tell her that I met a strange lady named Mrs. Potter, who had a really cool tree in her front yard and had me clean out her gutters and had some more work for me to do next weekend for money. Yet, for whatever reason I kept this to myself just long enough for Mom to change the subject.

“How about you call your brother tonight,” she stated more than asked. My older brother, Hunter, had been living in Ellsworth with Dad for almost two years. We both lived with Mom the first few years after Dad left, except for every other weekend when we visited our father, but then Hunter stopped doing his homework and kept fighting with Mom about it. They fought about other stuff too, like him not doing the dishes or his laundry unless she begged and disrespecting her generally with his sullen faces and guffaws, those fart sounds he made through his lips, and not being a very good male role model for me. Then he got into an actual fight with Rob Corning during P.E., not starting it (but still), and Dad thought maybe it was best if Hunter came and lived with him for a while, and Mom, shockingly, agreed. Hunter tried to get me to leave Mom for Dad too, because Ellsworth was way cooler than our bumfuck town, and Dad never hassled us about our schoolwork, or anything else really. But I could never leave Mom, even if she would have let me. Plus, Dad never asked me to live with them. So, I stayed with Mom, who repaid my loyalty by making me join Boy Scouts.

“Okay,” I conceded. I’d call my brother after dinner. We weren’t very good on the phone as a general rule. Mostly we just listened to the air through our crappy cellphones, salted with static, Mom or Dad barking in the background time to time over what news from the week we might share. Hunter was almost three years older, which seemed like a lot. Too, the longer we lived with different parents, the less we had to talk about, even the one weekend a month we both stayed at either Mom’s or Dad’s place.

“You be okay, Luke, if I see a friend tonight?” Mom asked as she cleared our plates. I said sure. She had “seen” a few “friends” since the divorce, men she knew from high school or met at the diner, or maybe even online for all I knew. I’d only been introduced to a couple of them. Nothing seemed to stick. I wasn’t even certain she wanted another man around full-time. I certainly didn’t.

Mom headed upstairs to shower up for her date or whatever and I cleaned up the kitchen in the half-assed but acceptable manner in which I specialized, remembering at least to put back in the fridge the huge green can of parmesan. She had brought me home a slice of banana cream pie from the diner, I noticed, which I was looking forward to eating while I watched three or four episodes of the sailing show on YouTube. First I had to call Hunter and Dad, though, because I knew Mom would make sure I’d called them before she left.

When Mom finally creaked down the stairs in jeans, she smelled like flowers again and baby powder. She combed her splayed fingers through her hair, still dark with wet, leaning sideways so as not to get the wet all over her fuzzy sweater and sort of blocking my view of the TV from my spot on the couch. Hunter, meanwhile, hadn’t answered his phone, but shot me one of those annoying as fuck Sorry I can’t talk right now texts. I was just about to tell her that I tried calling when she started talking: “It’s just Ellen I’m seeing for a drink or two,” she said, as if to say, It’s not a guy. To which I said, “Oh,” as if to say, Oh, because I really thought that it must be a guy. Ellen Hertzog was Mom’s high school friend, who moved back to town a while back.

“We’ll go to the movies tomorrow, how about that?” I didn’t like sitting through movies at our tiny theater with the crappy seats, which Mom knew but somehow couldn’t bring herself to accept.

“Sure,” I said.

After canvassing outside Hannaford grocery up in Machias the next Saturday ($34, total), I changed out of my Class A and rode my bike to Mrs. Potter’s house, the wind cutting through my fleece, Hunter’s hand-me-down. I’d hold out long as I could this season before breaking out my parka. I almost crashed and burned down her steep hill as my brakes needed tightening. It was a prettier day than last week, the cold sun spearing through the gray to redden up the sweet gum leaves even more, or maybe the ones left up there were just riper now on the tree. I noticed a burlap sheet strewn across the ground so figured that raking leaves was what she had in mind for me today. I wasn’t wrong about this.

Soon as she answered the door, wearing pants with sharp creases down both legs, she led me around the back of the house to an ancient shed. She handed me the same suede gloves, softened up from last week, then spun the dial on the combination lock and slipped inside. A dog barked and barked through the woods from some house not too far away, I figured, whether at us or a deer, or just to hear itself bark, I wasn’t sure. Way too big a dog to be one of the Ackincloses’ little Frenchies with the funny ears. They lived much closer to town, anyway. She emerged with a steel-toothed rake and explained what she hoped I could accomplish out front the next few hours, rake sheets of leaves onto the burlap, then wrap up and drag each pile to the curb. There were a lot of leaves so I shouldn’t try to do it all today. She’d call someone to haul the pile to the transfer station, as we weren’t allowed to burn them anymore.

“How about we settle on terms, young man,” she proposed as she handed me the rake. I told her that she didn’t have to worry about money, that I didn’t have anything else to do this afternoon and that I was happy to help out. I hadn’t really planned on offering my services for free, and I wasn’t entirely sure why I was doing so now.

“You want to go to Tennessee, ayuh? That’s what you were going on and on about last week.”

“Yeah,” I said. “Sure.” I did want to go to Tennessee, I realized only after she reminded me. “How about five bucks an hour?” I proposed, which seemed to amuse her by the way she showed her white teeth.

“You won’t make it to Bangor on five dollars an hour, young man, much less Tennessee. Let’s make it eight dollars, ayuh?”

I threw myself into the work with terrific enthusiasm, an enthusiasm I never would have applied to our own property had Mom and I lived in a house with a yard. All the same, raking up layers and layers of moldering leaves and big seedpods pretty much sucked. The rake’s teeth weren’t stiff enough for these crusted leaves. I had to press real hard to get under any of them and could only clear a few feet or so every sackful, deep as the leaves were crusted before they yielded to what might be considered bare ground. I wondered how long I’d put up with the towering sweetgum above me had I been in Mrs. Potter’s shoes. I could feel my breath growing hotter against my teeth and the cold air as I raked and raked, wrapping over the four corners of burlap and dragging the Santa Claus pouches to the curb. The sweet-sounding birds were long gone already for the winter, but invisible juncos still filled the air from time to time with their shrill complaints. The dog kept up its barking too beyond the shed somewhere out back so maybe it wasn’t barking at us but just wanted food or attention or something. Maybe an hour had gone by when Mrs. Potter came back outside and asked if I’d like to come in to take a break. By this time the sun had already dipped below the spruce line, hiding itself from her hollow, though it wasn’t nearly nighttime yet. My lungs were burning, and I could feel a blister rising inside my left thumb, despite the gloves.

I took off my dirty shoes and left them on the landing before following Mrs. Potter inside. She seemed to have turned on more lights since last weekend and it smelled a whole lot better, outdoorsy notes that were sweeter than the spice of our local woods. I followed her down the hall toward the kitchen. She had changed the cat litter, I gathered, vacuumed up the strange carpet using a deodorizing powder that smelled of citrus—I finally placed the pleasant smell—or maybe it was furniture polish or one of those plug-in deodorizers that smelled like an orange. She’d cleaned and tidied as if I were company, which I supposed that I was. I inspected the photographs in the frames along the way, collages of nature scenes and portraits, a younger Mrs. Potter (her hair had been brown) and the same man in some of them with the part in the middle of his hair and the mustache hiding his top lip. He wore athletic shorts in one photo that might have been in fashion like forty years ago, cut high with white piping up the tapered sides.

A new smell greeted me as we entered the kitchen, like Chinese food. The kitchen looked not unlike our own kitchen, by which I mean it had linoleum floors and Formica countertops rather than the tile and granite I was starting to see in other people’s houses, Boy Scout events, birthday parties and whatnot. It was bigger and cleaner than our kitchen usually was, though, as I tended to leave my dishes piled in the sink when Mom wasn’t home. With the blade of her hand, she invited me to sit at one of the two green vinyl chairs at a small round table. The vinyl on my seat was raised in three complex tributaries of a slightly darker green, a repair job that might have come out better. She poured water into a glass from a large plastic container she retrieved from the fridge, then handed me the glass at the table.

“I took a class on cooking with local seaweed at the Y a while back,” she said as if to explain the kitchen smells she might have noticed me smelling. “How about you give my dulse stir-fry a taste with your water and tell me what you think?” She retreated to the electric stove and the cast iron pan, anticipating my positive response.

I didn’t know what dulse was, but I figured it must be the purple seaweed on the plate she set before me swimming in a dark sauce between baby corn and broccoli and other reedy-looking vegetables I couldn’t name. It tasted okay, I guess, if a bit slimy. She had given me far too large a portion, a meal-size plate with rice on the side rather than the “taste” she had proposed. “It’s good,” I said. She sat and watched as I chewed another bite. I wasn’t sure how much I’d be able to eat.

“So’s that man in all the photos your husband?” I asked, partly so I could stop chewing.

“No, my husband left years ago. Good riddance. The man in the photographs was our son.”

She let that was hang up there for a while, or maybe I was the one who let it hang up there, as I guess it was my turn to talk. A cat angled into the room, though not the same cat I glimpsed last weekend. This one was all black and long-haired and she greeted it by its name, Theodore, which seemed an awfully human name for a cat. Theodore meowed and she must have performed the translation, because she rose and scooped up some dry kibble from an enormous, repurposed plastic container on the counter, poured the scoopful into a metal bowl sitting on the linoleum beside the pantry.

“He died of AIDS-related complications,” she said. She placed the measuring cup back into the plastic container, twisted the lid shut. “He was a homosexual.”

I didn’t really know how to respond to something like this, so I just put more food into my mouth.

“That’s not going to be a problem for you, ayuh?”

“No,” I said, reflexively, as this was clearly the correct answer, though I wasn’t exactly certain what she meant. I figured, at first, that she was making sure I wasn’t gay and so wouldn’t be having a problem with that disease. But then it dawned on me that what she really hoped to ascertain was that it wouldn’t be a problem for me to come by her house every once in a while to help her with some chores, or sit in her kitchen, now that I knew that her son had been gay. Which told me that it must have been a problem for other people around here back in the day, people her age like Mr. and Mrs. Ackinclose, and maybe her husband, too, who left years ago and wasn’t in any of those photos on the wall.

She was lonely, it occurred to me for the first time. That’s why she answered the door when I knocked last weekend, even though she had a No Soliciting sign up that I might have noticed. Next instant, I was seized by those hiccups again, as I realized that I was lonely too. Hiccup. I drank some of my water. Hiccup.

“It was a terrible plague that swept across the whole country and the whole planet,” she was saying now, scrubbing at the sink basin the cast iron pan she’d dirtied. “It’s still around, and bad some places, but not as bad as all that here, anymore.” The heavy pan clattered against the steel sink as she scrubbed and scrubbed. “It’s something you can live with now, judging from all the black people in those television advertisements.”

I wasn’t sure I liked the way she said black people, not that I knew too many black people at the time. Only Will Shearson, who worked back-of-the-house at Teddy’s and slipped me whoopie pies he just baked, those evenings I did my homework on one of the barstools at the counter.

“I’m sorry about your son,” I said, shuffling a piece of baby corn around on the plate with my fork. The hiccups seemed to have gone away. “I guess he was really young.”

Here she turned off the fizzy tap water and turned to look at me, as if I’d said something funny, or something she didn’t quite hear. “He was young,” she replied. “Not everyone gets to be old, Lucas.”

She came back to the table with the pitcher of water to give me a refill. The dog had stopped barking outside, but I could still hear the juncos through the thin kitchen window carrying on in the scrim of woods as the water rose in my glass. She sat down and told me some more things about her dead son while I took careful sips of the water. His name was Brian and he had taken most of the nature photographs floating in the frames all about the house. The granite shoreline all along the Maine coast was his favorite place to shoot, before everyone made a mess of it. Runoff from the paper mills, people with their plastic. He was a talented photographer, back when you still had to know a thing or two about taking pictures to take any good ones. It was all about the f-stop and the shutter speed. He worked for the Associated Press and they sent him all over New England to this and that news story, which mostly involved people. His photographs were published in newspapers all around the world, back when they still had newspapers. He’d tried Boy Scouts with Frank Ackinclose, who did his best, but the other boys weren’t very kind to him. The more she talked, the more it seemed to me that the world Mrs. Potter lived in now was very different than the world she once knew, a world which used to have cleaner oceans, more complicated cameras, and print newspapers. Plus her son, whose name was Brian. I also realized, maybe, why she couldn’t bring herself to chop down that huge sweetgum tree causing all manner of trouble to her house, living out such a long and unlikely life in our cold northern woods.

Mom and I drove to East Machias to go bowling that night, which I liked better than the movies, and I scored my first turkey. I called Dad and Hunter from the car on the way back home to tell them about it and they took turns trying to sound impressed. Hunter’s voice sounded more and more like Dad’s voice, lately. He’d gotten a weekend job at the dock in Stonington, he told me, baiting, loading, and unloading traps, re-painting buoys and whatnot, because he was old enough now and Dad knew someone. “Awesome,” I said, and then Mom took the phone and told Hunter in that tight voice she used sometimes to tell Dad she would talk to him later, which meant that she didn’t want to hash out whatever she had to say to him in front of Hunter and me.

We ate big bowls of Moose Tracks ice cream when we got home, and then I told Mom I was going up to bed. She reminded me to brush my teeth, as I knew she would. After I brushed my teeth (poorly), I watched an episode of that sailing channel on YouTube in the bedroom I used to share with Hunter. It wasn’t such a good day for the family. The man speared a big fish while free-diving along a tropical reef, a snapper he called Cubera. The wife baked the fillets, thick and wide as catcher’s mitts, with butter, lemon, and pebbly things she called capers. But the fish made them both really sick. (The sandy-haired kids had eaten mac and cheese from a box so they didn’t get sick.) Some big snappers like that were filled with a toxin, the man said through his mustache, splayed out on the bed, covering his face with his elbow as if the light hurt his eyes. It wasn’t always so thrilling, apparently, sailing between French-sounding Caribbean islands. This made me weirdly happy for just an instant before I felt bad—feeling happy about other people being sick.

I saw Mrs. Potter quite a bit over the next months and years, which is to say I saw her sometimes. She’d call my cell odd weekends from her landline, and I’d come over to do this or that odd chore. Autumn, there were those leaves, of course. Wintertime, I’d shovel snow from her driveway and front walk. Turned out there were some pretty flagstones leading up to her door beneath that crusting of moldering leaves. Once spring came along, there was some patchy lawn to mow and her garden beds to tend at the edge of her property beyond the reach of the sweetgum’s shade, flowers and shrubs that weren’t much in evidence those first frosty months I knew her. She tended to those beds with great care, despite the lack of sun in her hollow and the lack of encouragement from her immediate neighbors, who didn’t seem to have much use for pretty things. I’d drive with her to help her pick out plants—bee balm, columbine, black-eyed Susan, bunchberry, rugosa, white beard-tongue—and loaded them in the Subaru for her along with soil and other supplies from the nursery, Meadowsweet. It was owned by Gilbert Wisner, that fellow she mentioned the first day we met. Helping Mrs. Potter with her garden was my favorite thing to do over there. She’d let the cats out to keep us company. They slinked around her pleated legs, never straying far.

During the off-season, she’d sometimes summon me just to start up the ancient mower from the shed so the engine wouldn’t freeze, or move musty-smelling boxes around her house, or put them in the back of her car so she could take what was inside to the Goodwill up in Machias. A couple times I helped her take the cats to the vet. The tabby, Morris, scratched me up something good the first time I tried taking him out of his carrier. Sometimes when we were together Mrs. Potter asked after my schoolwork, or Mom, or what badge I was working on for scouts, or she’d remark upon the latest kerfuffle (her funny word) in town: the defunct granite quarry the owners suddenly wanted to sublease, the new traffic light top of the hill that might or might not have been a waste of taxpayer money, Acadian Seaplants, which seemed intent (according to Mrs. Potter) on stripping the whole coastline of its rockweed, the new Walmart set to open up somewhere closer than Bangor (it never did). She didn’t talk about these things the way other people did, Mr. Ackinclose or any of my “male role models.” Mostly, though, Mrs. Potter and I didn’t talk about much of anything, which suited the both of us, I think. Mom knew about Mrs. Potter, of course, that I performed odd chores over at her house from time to time for a few bucks. Yet I never really told Mom very much about her, and Mom, for whatever reason, didn’t ask. Maybe because she had her own life, which included people she didn’t tell me very much about, either.

Then I stopped seeing Mrs. Potter. My Eagle project, restoring neglected stretches of trail in the state forest just outside the town limits, took up more of my time than seemed reasonable. Homework got tougher too, as I hoped to go to college and tried hard to earn solid grades, not being one of those kids whose father ran a boat with eight hundred traps, and not being one of those boys drawn to our frosty sea, regardless. I had joined the school chorus, too, mostly because it—somewhat nonsensically—exempted me from PE. It’s not like I rebuffed Mrs. Potter outright, except for that one time when I was pressed with Chem homework. Surely she would call again if she truly needed me, I thought.

It was during this period that I glimpsed her in town by chance for the first and only time. She didn’t come to town very often, at least not during times that I happened to be there. I was just stepping out from the coffee shop with a few of my chorus friends between school and rehearsal, the paper cup burning in my hand, when I glimpsed her stepping outside the post office the government was always threatening to close other side of the street. Something about the height and posture of the old woman over there signaled to me instantly that it was Mrs. Potter, causing me to freeze in my tracks for a split second, during which time she might have glimpsed me, as well. I can’t be certain of this, however, because it was during this split second that something shivered inside and I pretended not to notice her. Then Kay, the girl I had a stupid crush on, said something that was supposed to be funny, so I laughed on cue and followed her and my few other friends back down the street toward the high school.

It filled me with shame that I’d pretended not to see Mrs. Potter, who—yes, I was certain—had been standing there across the street waiting for me to notice and acknowledge her. I carried a stricken look on my face right into rehearsal, apparently. We weren’t halfway through that Sondheim tune before Mrs. Mascolo held us all up and asked me if I was feeling okay. It took me almost the whole walk home in the gray cold to search myself and figure out why I’d pretended not to see Mrs. Potter. It wasn’t that I was embarrassed of her in front of my friends or anything like that. Rather, I felt guilty for having neglected her for so long. I only hoped that having seen me, she didn’t notice me pretending not to see her.

Months later, just before my high school graduation, a simple cardboard box with my name on it appeared on our stoop beneath the awning. Someone must have dropped the package off as there were no postal markings on it. I brought it directly inside to the kitchen table and tore into it with scissors. Inside the box were some of those mint-colored packaging peanuts and then another smaller box wrapped in gold paper, and inside that box was a red envelope and a Pentax camera, which was surprisingly heavy. I knew before even opening the envelope and reading the card that the package was a graduation gift from Mrs. Potter and that this must have been one of Brian’s cameras. The card told me that it was her son’s very first “real” camera and that she hoped I’d take the initiative to learn how to use it, because using a real camera with real film was something a young man should know a thing or two about, and she knew that I’d be meeting all sorts of interesting people and seeing exciting new things at college. She named the specific college that I would be attending, one that had offered me an academic scholarship, and that’s how I discovered that Mom and Mrs. Potter did talk to each other about me. I was fairly shocked by this, and equally shocked that she had remembered me on my graduation. We hadn’t been in touch for over a year, which seemed like an awful long time to me, but maybe didn’t seem like very long to her.

I wrote her a thank you card for the camera, of course, and after receiving it she called my cell to invite me over for lunch. At the metal table she kept out under the sweetgum tree, we sat down to bologna sandwiches and fiddleheads she’d just pickled, Theodore circling my legs and purring all the while, happy to see me. Her thin hand trembled for a moment over the lid on the Mason jar holding the fiddleheads before she slid the jar across the table for me to open. She asked me a few questions about the college I’d be attending “down south,” by which she meant Pennsylvania, but we didn’t talk any more than we usually talked. I mostly studied the goldfinch mustarding the garden, working its way across the heads of some thistle I didn’t recognize. The garden beds were a riot of color, the rugosa hips near bursting, pollinators looping all about the black-eyed Susans and the fuzzy purple heads of bee balm. It was good to see her keeping the garden up and I told her so, which made her smile in an amused way. She’d been tending her garden for years and years before I ever started helping her with it. Mrs. Potter’s skin looked a bit yellow to me in the outdoor light, but I hadn’t thought that she might be sick. Nor did I realize that it was kindness, her final kindness to me, and not weakness or pride, which compelled her to slide the jar of fiddleheads across the metal table for me to open, hiding her frailty from my eyes the best she could.

When Mrs. Potter died the next year (renal cell cancer, which I’d known nothing about), my mother mailed me the obituary she had cut out from the local paper. I read it carefully in my dorm room. I wasn’t used to reading obituaries and it felt funny to read one about a person I knew. Or thought I knew. She had lived practically an entire lifetime, after all, before I popped in at the tail-end. Someday, if I was lucky enough to be one of those people who got to be old, Mrs. Potter, I realized, would become a smaller and smaller part of my life, which made me sad. Boy Scouts and those crazy spaghetti dinners and Dr. Hargrove and Mr. Ackinclose and Connor were already sort of fading into the backdrop. Tennessee, too.

Because oh yes, I did get to go to Tennessee. Of course I did. Everyone in scouts got to go to Tennessee and all those other summer places that we visited, no matter how much or how little money we managed to raise. The troop was good in this way. I liked Tennessee more than I thought I would like it. All the places had interesting names and the woods were painted a lighter green than our woods. The days were wicked hot, but all those caverns were deliciously cool, which I didn’t expect. At my favorite cavern, Tuckaleechee (see, names!), I learned how the dissolved minerals in rainwater flowed through the limestone to form those stalactites and stalagmites slowly, oh so slowly, less than 10 centimeters every thousand years. It took my breath away when the guide told us this beside the noisy underwater falls. Then she turned off the lights and all that remained in the entire universe were those invisible falls splashing against the rocks. Connor was right about it being the darkest dark I could ever imagine, so dark that my eyes didn’t quite know what to do floating in their sockets, which was a weird feeling to feel. I had to clear my throat to remind myself that I was still me, that I was still here on this earth, inside the earth, in this very small way.