I Write for My Beloveds

Javeria Hasnain interviewed by Shlagha Borah

Shlagha Borah: I am always intrigued by titles and I want to know what came first, the title or the poems? Did you write towards this central theme in mind or did you see the threads connecting over time?

Javeria Hasnain: I had begun writing these poems immediately after moving to the US because I kept hearing people from one sect to another, or one religion to another say, “You’re a sinner because you’re doing such and such,” and the word becomes a defining part of your identity, but also loses its meaning, and I wanted to write about that. Titles came afterwards, the poems came first.

SB: There are so many mentions of god in this collection. Tell us about the role of religion in your life while you were growing up.

JH: My parents have been traditionally and culturally Muslim, they pray five times a day, we celebrate Eid and fast for 30 days of Ramzan, and they’re very particular about some things like, no sex before marriage, no alcohol, no haram. But I wouldn’t say it was orthodox because we grew up watching skimpy women dancing in Bollywood films. Let me tell you something that defines how we were as a family – We used to do a lot of sleepovers at my Nani’s house, and my Khala would wake up and pray Fajr (morning prayer), and immediately after, while she is still counting the Tasbih beads and praising god, she would turn on the tv and put on the most raunchy music videos ever.

There has always been an oscillation – there was a point in my life when I used to do the Hijab, I don’t anymore, but I am still constantly thinking about god and spirituality, what kind of life I want to live, etc.

SB: In what ways has your relationship to god/religion changed after moving to the States, and how does that show up in your writing?

JH: What I have become accepting is the fact that I enjoy the uncertainty, and that this is the work of a lifetime. I am not looking to get answers if god is real or not. My preoccupation is, how can I live a life that is fulfilling and how I can love better. How I can love my friends, my community, my parents, god, and that’s how I am thinking of god these days. I am not following the conventions these days – I don’t pray or fast, except on my dad’s death anniversary – but those things are still close to me.

I am a very firm believer of seeing god in people, and knowing god through people. Also, I read and listen to Sufi poetry a lot, and have been trying to write towards that ancestry and lineage as well.

SB: Talking about lineage, you are actively doing the work of translation, even if not directly. Growing up in a particular culture and then manufacturing it for a different, more Western audience. What are some of the challenges you’ve encountered or questions you find yourself asking?

JH: In my MFA, we had a very diverse, international cohort, and we were all writing about our lands. So many people had curiosity, questions, and genuine interest. I had an Indian and Pakistani poet in my cohort and the kind of nuance that they would understand was unmatched.

I don’t want to cater to a Western audience; I am still writing for beloveds, friends, and family. Say a poem has four layers, and maybe without certain contexts one is able to peel off only the first layer, versus if one understands the language, they can peel off all four layers. But my goal is that, even if my reader is from a background where they’re not familiar with any part of my culture, they’re still able to peel off that first layer.

SB: The embodied moments of this collection make it so sensually rich. In “Tangerines,” you write, “Whenever I come,/ I think of god.” And in “Body is a sin,” “I am so often touched. So often moved. And yet remain still.” I wouldn’t call these direct contrasts but I’m wondering about moments where the speaker feels present in her body versus when she is dissociated, and how that directly translates to her relationship with god. The speaker is constantly oscillating between devotion and desire, until the lines are blurred, and I am forced to ask myself, which is which? Are they even separate? To me, it feels like the moments where the speaker feels closest to her body are the moments of heightened spirituality in the collection.

JH: I am currently thinking of Sufism, songs in shrines or in Bhakti where one is feeling so intensely, they are in a transcendental state, and it’s an extremely embodied experience. It is not something I do intentionally on the page, whenever it happens it happens. When it doesn’t, it doesn’t.

I am learning so much from the body’s wisdom. The body knows even when I am not aware of it. I am trying to listen to it and respect it more.

When I started writing again after losing my father, it was a very heavy experience on the body, and that was the first time I understood what people meant by poetry being an embodied experience.

SB: What are some of the discoveries you made during or after finishing this project?

JH: The moment when I most realized that I have a book was when I was gifting it to people, writing my little notes. In retrospect, that is why I wrote the book, to write notes to my friends.

SB: This is kind of related. So many of your poems are for, and to, women. Would you say that’s your community?

JH: I am constantly thinking about my girls, especially who is allowed to be here, in the US, in New York, to create this kind of work. I am thinking of girls like me who cannot be here for financial, domestic, societal reasons, and trying to do my best. I never think of myself as a spokesperson for anyone or any community, I just write what I would want to hear or read.

SB: Was there a defining moment when you realized, “Oh, this is what my work is about!”

JH: In June of 2023, I was at the Rockaway Beach and I wrote a poem titled, “At the Rockaway Beach, I think of my girls in Karachi” where I wrote about my friends and cousins being at the beach together, and that was kind of the moment. But before that, I just started writing my experiences, and so many of my friends and acquaintances from college told me how much they resonated with my work, and I was like, “I literally write for you.”

SB: Has your relationship with desire, or the idea of “sinning,” changed throughout the journey of this book?

JH: Desire is still elusive, so I am in that same direction where nothing has been resolved yet. Or, to put it another way, it is perpetually changing so it is never fixed. About sinning, I am very judgmental to myself, and when one is judgmental about oneself, one is judgmental about others. I am trying to become less judgmental, and a little less quick to respond or say something.

SB: Is there a particular feeling or take away you want the reader to leave with, or moments you wish they would return to, after they’ve put down the book?

JH: I don’t think about what I want them to take away. I just want them to enjoy the book, appreciate the lyricism, and have a good time!

SB: What project(s) are you working on at the moment?

JH: I am working on my MFA thesis, which is going to be a full-length version of the chapbook. It talks about desire, god, matrilineage, and traversing geographical and mystical landscapes to find belonging and self (or multiple selves).

SB: You write a lot in form, especially ghazals, couplets, and prose poems. Would you say the content informs the form, or vice versa?

JH: Both. Sometimes I intentionally start with a particular form, and then the content has to mimic it. But other times, I just start the poem and see what form it takes. I would say it’s a balanced relationship. But I do love writing in form. I love having structure to my things, and maybe it also comes from a need for control?!

SB: What’s your favorite form? Is there a form that you’ve been meaning to try but haven’t?

JH: Favorite form is, hands down, the ghazal. The first name that comes to mind is Agha Shahid Ali. A form I have been meaning to try, is to write an eponymous poem about my name but haven’t gotten to it.

SB: Give us a writing prompt!

JH: Write an eponymous poem on what your name has been mistaken for, and who you would be if you were that person. For instance, when I moved to New York, a lot of people pronounced my name as “Hav-ee-ay-ruh.” What if I was her?

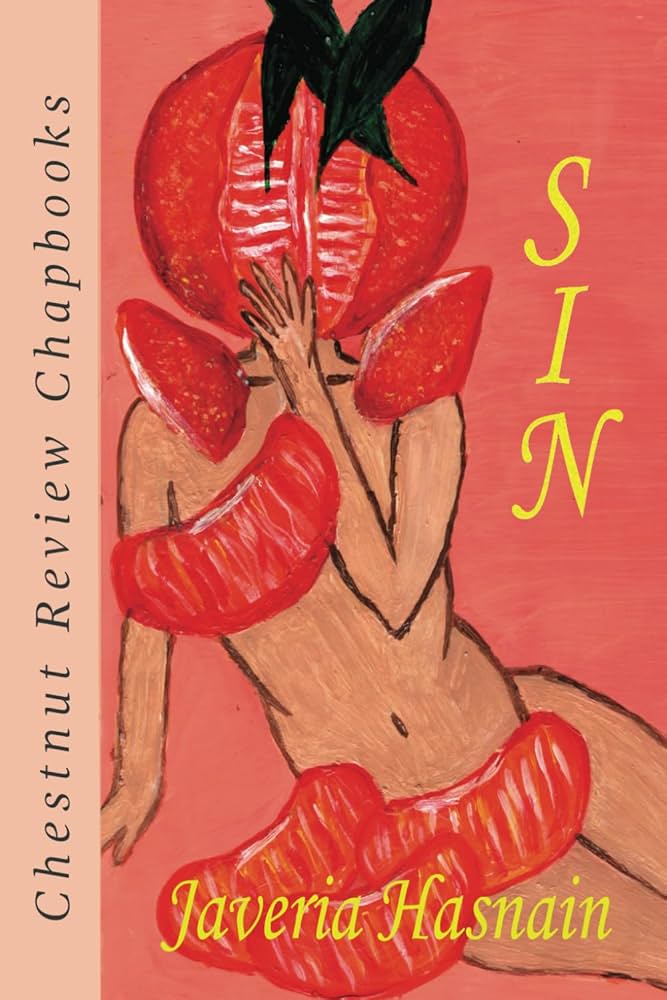

Link to SIN: Chapbooks – Chestnut Review