Trees Speak

Li Sian Goh

“How interested are trees / in matters of outrage and injustice?” – Cyril Wong

It’s a week to curtains, and the playwright is getting anxious because he hasn’t heard back from the censors yet.

One could kick up a fuss, he has in the past. The problem is that to kick up a fuss, one must know the actual lines that are so contested. The censor must determine scenes, storylines, political issues to be cut. Only then can one take to social media to post outraged screeds about what the Singapore government is attempting to censor next: The Media Development Authority is censoring artistic truths about racism/homosexuality/domestic violence/history/elections! Have you ever heard of such a thing? The Greek chorus of outraged netizens commenting in solidarity will profess that no, they have never heard of such a thing, at least until next time.

For this is the game: the playwright writes. He clears a space, he writes a first draft and revises it for a second and a third, he thinks about his favorite actors’ voices and faces, and he goes to shape certain lines around them. For playwriting is unique amongst literary forms in that a play is not most complete in the act of creating itself, but in the act of being interpreted by intelligences alien to oneself. He brings the play to his director. Between the two of them they discuss visuals, they discuss affect. They reshape the play some more. Rehearsals begin. Sometimes the actors go off-piste, they suggest line changes, which the playwright rejects as gracefully as he can. Then they submit the script to the MDA.

Once, near the start of his career, after a particularly brutal cut, he had persuaded the director to stage the letter of notice from the Media Development Authority that had said they could not stage those scenes, in place of the scenes that were cut. To dramatize the previously invisible, if you will. At the time, the playwright had been twenty-seven, he’d felt good about it, angry but good. Angry and good. Still, the staging of their resistance had been ephemeral. (Like all good theater is.) It wasn’t something that could be done every time before becoming one-note, though censorship is inevitably that, one-note, and the year after they had staged that play the Arts Council had cut funding for the company, so it was a no-go.

At the start of his career they called him so many things. Enfant terrible, angry young gun. Now? He’s old. Lately, more than anything, the playwright is tired. He is tired of launching the ostensible wrecking ball of his words at “community standards”, at “national security”. Where, once, he would have termed it a badge of honor, he is tired of being quietly and not-so-quietly labeled a traitor. He is tired of out-running, out-gunning, out-maneuvering the powers that be, who year by year churn out ever more sophisticated censors, fresh graduates in English Literature from the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. Oxbridge—a colonial hangover if there ever was one! He is tired of scrutinizing his own work for the stench of self-censorship, and he is tired of assessing how, despite all this, he can assemble, through his words, the bones of a performance that can bend a curve past censorious interlopers to strike at the heart of the audience.

The theater no longer holds, for him, the fervor of a young love, a first love, but the worn-out, disillusioned love of a marriage that has nevertheless shown its staying power. And his plays? They’re no longer vehicles by which he nurtures, any longer, hopes of stirring the consciences of kings. No, more and more, plays are the thing he does simply because they are what he has always done.

Still, one goes on with the day-to-day. The play is submitted to the MDA, the cast gets on with rehearsals, the playwright sweats, and the entire company sweats with him.

*

Jiaying is sweating. The air-con in the theater is running, sure, but she’s been lifting and carrying, the days grow hotter and hotter, and whoever the asshole cheapskate is who’s in charge of such things, they have not turned it on low enough.

The job is turning out to be more complicated than expected, even by theater standards. She’s worked with Sze Mun, the production manager, before, and Sze Mun tipped her to build out the set and crew when the opportunity came up. Crew for a homoerotic play about trees written by someone who, despite being a bit of an egotistical ass, is after all a doyenne of national theatre and a queer elder? How could she ever say no?

Yes, she had to put her karate instruction gig on pause, and yes, she had to tell the gym she wouldn’t be available for personal training sessions for a while. But who cares when this opportunity could lead to… more precarious, temporary, high-prestige and low-paying gigs like this, actually. Career progression in the arts is a joke.

Jia takes her snapback off and runs her hand through her hair before putting the cap back on, carefully adjusting it so her fringe is pulled back and doesn’t drip sweat into her eyes. She thinks about Louisa, with whom she stayed over last night. She met Louisa at the gym where she provides personal training sessions, then they bumped into each other outside of it. Outside of the expensive workout clothes Louisa wore to their sessions, she was a vision, well-appointed in structured jackets and silk scarves. Tasteful. Classy.

Louisa is forty-eight to Jia’s twenty-seven. Until a few years ago she was married to a man, and the first time Jia came over to her expensively furnished apartment they drank deep, dark, rich wine from wineglasses with oversized bowls. Jia swirled hers too enthusiastically—she’d read that you needed to do that to wine, to aerate it—and it had slapped right out of the glass, like a tidal wave. Louisa had laughed, fond and indulgent, and they’d gone to bed anyway. Jia’s mouth waters just thinking about Louisa’s body. She’s told her as much: “It turns me on just thinking about you.” Louisa had laughed at that, too. She said: It turns me on to think about you thinking about me. Then, for a while after that, neither of them did much thinking.

Recently, Jia has been sleeping over at Louisa’s two or three times a week. That’s another nice thing about dating someone older—there’s no sneaking in and out so as not to alert anyone’s parents, no frantic coming-out crises, no fake boyfriend as a smokescreen—all of which has happened to Jia in the not-so-recent past. True, Jia hasn’t met any of Louisa’s friends yet, but that’s because they spend much of their time falling into bed together. Just yesterday, their fingers intertwined, Jia had brought Louisa’s hand to their mouth and kissed the back of it and said, “Can I call you my girlfriend?” Louisa had burst into laughter and said: Oh, my dear, you are so sweet, but I’m so old, how can I be anyone’s girlfriend? It wasn’t quite a yes, but it wasn’t a no, either, and Jia is thinking she’ll bring it up later. Reassure her that she finds her entrancing, forty-eight years old or no. Maybe that’s even part of the appeal.

Louisa is coming to opening night. “Wouldn’t miss it for the world, darling.” Jia bets she has really good seats, Class A if not front row. She’s bringing a friend, apparently. Louisa seemed to think Jia and the playwright were on a first-name basis, and Jia did little to discourage the assumption, when the truth is that she’s just another anonymous worker bee on one side of the unspoken class divide between cast and crew.

Just as the air-conditioning is finally kicking in, Sze Mun comes over and looks at the bulky wooden boards Jia has deposited on the ground. Her mouth tightens with impatience, although her tone is deliberately neutral when she says, “That needs to go to stage right, not stage left.”

“Sorry, Z,” Jia says, and obediently picks it all up again. By now, her sweat has sweat. What is unspoken between the two of them remains unspoken: that Jia has been spacy lately, that she needs to get her head in the game. Sze Mun knows that Jia is seeing Louisa, although she, typically circumspect, hasn’t said anything since the time they all ran into each other at 28 Hong Kong Street. Louisa and Sze are closer in age than Louisa and Jia are, in fact Jia knows they know each other, and when Jia (not being able to ask Sze) had asked Louisa about it Louisa had said airily, “Oh, her,” and not bothered to explain before they had gotten… distracted. Jia’s not an idiot. She detects history there.

Still, Jia supposes Sze is right after all; she needs to focus when she’s at work. She looks up to Sze, Sze is a mentor to her in many ways—you don’t get many female theater practitioners in Singapore, at least not on the production side of things. (There aren’t any speaking roles for women in this play either—by the playwright’s estimation, the trees of the secondary rainforest are exclusively male, although to be honest, that’s just as well. Jiaying has seen one or two plays by the playwright that did feature female roles and well, they weren’t very good.) Still, thinking about Louisa is more entrancing than work, than building out the little world that is soon to be inhabited by the lost boys of SG theatre. Who can blame her for wanting to dream a little longer?

*

Devan has dreamed of this. So don’t get him wrong, Devan is truly very grateful to be cast in this play and he is truly very excited about the production and the opportunity to be making art. This is it, right? This is the moment of performance; this is the life. Just—why does the name of his role have to be Tree #3??

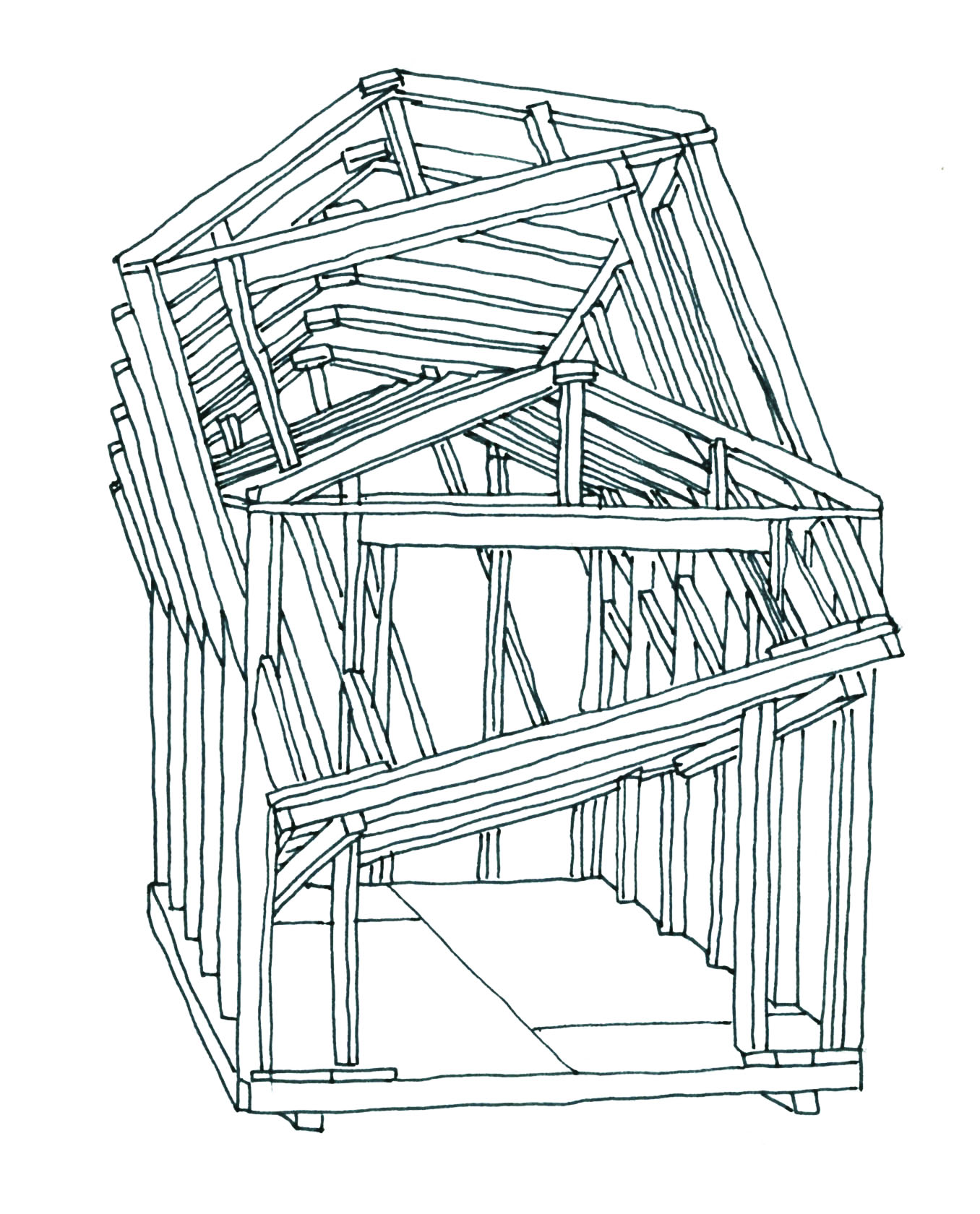

It’s a principal role because the play itself is about trees. Okay, more specifically: the play is about the policy decision to clear the Kranji secondary forest, and the night in the forest before the clearing starts. The trees move, the trees dance, the trees speak. They grouse and bitch and resign themselves to the oncoming ecocide, they promise to come back in the afterlife. It’s all very Waiting for Godot (which Devan still hasn’t read) meets Kuo Pao Kun meets the current yen for documentary theater, and Tree #3, contrary to all expectations introduced by the nomenclature, is a fabulous role. His character is presented onstage with the following description: Tree #3 enters. Or perhaps, being a tree, he was always already there. A stripling of a boy/tree, he wears a worried-looking expression that does not detract from the essential sweetness of his disposition. The eternal peacemaker, all the other trees in the forest are in love with him. The birds perch on his branches and sing sweet cantos.

Not bad, right? If he has to be a tree, you could do much worse than being a tree that all the other trees are in love with. As if. This is only his second time working with the playwright—the man, the myth, the legend—but already Devan wants to kill him. How the fuck does one appear on stage so as to give the impression of having always already been there? Also, it had been more or less implied that the playwright had earmarked Devan for the role from the start. Which should be flattering. Except that when he read his lines over again and again, Devan came to understand that Tree #3 is basically a twink. Which, Devan guesses, is how he himself fits in.

That name though. Maybe he shouldn’t have led with that part when he called his parents to share the news about having been cast. “Very nice…” his mother had said, somewhat unenthusiastically before trailing off.

“A tree?” his father had said sarcastically. “All of these years studying for some bloody made-up degree in theater studies, no steady career, and you are a tree?”

Devan had gritted his teeth. “You’ll see.”

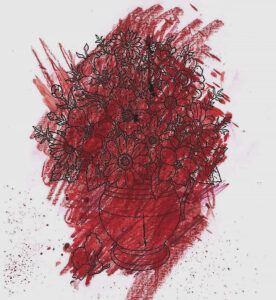

To be honest, part of him would rather they not. Despite the fact that he has been out to his parents since he was eighteen, and despite the fact that they’re ostensibly kind of okay with it, Devan thinks of his life in the theater, with long nights spent rehearsing, hiding backstage behind the ragged red velvet curtains, talking shit with his actor friends, as his real life. His queer life, separate and tucked up away from life at home with his parents. And this play… is kind of sexual. The entendres are kind of impossible to miss, all white sap trickling from gashes in the bark and seed pods tenderly plopping on the forest floor and trees sluttily displaying their wares, or waving their branches, in a light evening breeze.

Still, they’re coming, his whole family, for opening night. Devan’s parents, his brother, who’s on summer break from studying economics at Columbia, his brother’s white girlfriend who’s randomly visiting. It would be kind of sweet except that his dad was like, well someone has to support the arts, otherwise how will you starving artists eat. Devan said, “You know the state funds this stuff, right? They actually value what we’re trying to do here.”

“Ah, then you are a leech who can’t survive on a paying audience alone.”

Although Devan’s sick with nervous excitement about the run of the play—and yes, he does think it’s a good play, a great play—he’s sad. The beginning also means the start of the inevitable end, back to uncertainty, back to the anxiety of searching for the next role. But Devan tries not to think about that. Like everyone else, he is just doing his best. He will rehearse, he will do the tree makeup, he will enter from stage left as though he has always already been there, all along. He will enjoy the enormous pleasure of disappearing into a pleasure craft, carefully constructed for the specific form of play, both cerebral and kinesthetic, staged and spontaneous, that theater has to offer. He will be swallowed into the sole existence of the play, the play that is the thing.

*

The play is the next thing.

It’s been a good day at work for Amy Chia. She finished all the tasks in her inbox and it’s only 5:47 p.m. Well, all except one—her supervisor Dr. Jacob Koh shot her back an email when she told him it was done. Thanks Amy—since you don’t have much on your plate, I’ll add one more. Can you review this play and draft an advisory on cuts? ASAP, rush job, sorry for the late notice. Tks, Dr. Koh.

Amy thinks, though it could be wishful thinking, that the fact that Dr. Koh has asked her to review a work by this playwright is an indication of his trust in her. The playwright is known to be a grenade, an enfant terrible, whose plays could be anything, but are most often angry. Angry about the government, angry about society. This is the way artists are, they go around making up things to be angry about. Fictional forests with sentient trees, for example.

She would like to think that Dr. Koh is a mentor. Dr. Koh has degrees from both Oxford and Cambridge, he was a government scholar who finished his six years’ bond, and then went to America to get a PhD. Upon its completion, he reverted to the civil service. Dr. Koh spoke at the Institute of Policy Studies conference last year, delivering a speech on race relations and the need to balance artistic merit with community standards, particularly those relating to the range of interests in a multi-racial and multi-ethnic society like Singapore. In it, he stressed that the Media Development Authority had moved away from censorship in recent years. That in light of a maturing populace albeit one with new challenges in the twenty-first century, the Authority had increasingly moved towards classification, and under the new classification system artists and creators were invited to self-classify, to co-regulate the arts sector. All very reasonable stuff, things Amy had heard before, of course, but when phrased in Dr. Koh’s smooth, well-appointed sentences and sonorous delivery, the ideas themselves took on a new shine. She sees why Dr. Koh is widely considered a hotshot, someone with the potential to, one day, become a Permanent Secretary. She can only hope that, when he gets there, Dr. Koh will take her with him. She clicks on the paper-clip icon and the play slips into her downloads folder.

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

It takes her less than an hour to read the play, which is short. Her mind is flying ahead, plotting out the vagaries of the next hour. She’ll draft out the memo, go home, eat dinner, and then read over her work one more time before submitting it.

At one point, when reading the play, she wished she could have spoken with the playwright, or at least be permitted to make changes, not just cuts. To say: Why did you have to say that here? Maybe if you softened the language, I wouldn’t have to remove it entirely. She knows that is not the rational way. Helping doesn’t—shouldn’t—enter into it. It is this soft heart, she suspects, and not just her lackluster degree in communications from a local university, that sometimes gets in the way of her procession through the ranks of the civil service.

Never mind that. Fingers to the keyboard, mind to the task at hand.

Doctor Koh:

I have reviewed “Trees Speak”, a play written by aaaaa aaaaa and produced by aaaa aaaa. I provide a brief summary of the play’s content and thematic concerns below:

- The play is set in an unnamed secondary forest that is to be cleared for new housing developments, the day before clearing starts.

- The main characters in the play are the trees themselves.

- Some supporting characters are played by animals.

- The main concern of the play is the climate and the environment.

- Specifically, the play criticizes Singapore’s climate policy.

- The play also criticizes the clearing of Singapore’s secondary forest.

- The play criticizes also the extraction of sand from neighboring countries for land reclamation purposes.

- Finally, the play criticizes the establishment of eco-bridges over Singapore expressways, suggesting that they are “too little too late”.

- Additionally, there is both innuendo concerning, and explicit discussion of, homosexual acts within the play.

- As the trees discuss sexual intercourse, and all trees are played by male actors, the sexual intercourse that is discussed has homosexual themes.

I suggest that IMDA select one of two options. First, the play is classified as R21 and lines 25 to 47 on page 8 of the script are removed, from “What would you…” to “oceans”. These are the most overtly critical lines that could offend community values and pose a threat to national security. The R21 rating will ensure that the sexually explicit material is viewed only by mature audiences.

Second, the play is classified as NC16. In addition to the lines excised above, the lines 32 to 45 on page 56 of the script (“Just the tip…” to “white sap gushes out”) are also cut. This is in accordance with IMDA guidelines about scenes of a sexual nature.

Alternately, these two options can be presented to aaa aaa. Aaa aaaa can make the final decision.

Finally, the concluding form sentence:

Feedback from the arts sector, amongst various stakeholders, has been taken into account in formulating these guidelines.

It’s late, now. Time to go home. By this point in the evening her mother will have put the food from dinner in the fridge, a crease in her forehead as she does so. She thinks Amy’s work hours are too long, she thinks it’s the reason Amy turns thirty-four this year and is—still—unmarried. But Amy likes her job, it gives her satisfaction to know that the public service is just that, a service for the public. That every email she sends and every memo she writes up is somehow, transmuted through stolid, thought-out bureaucracy, cumbersome lingo and all, and added to the great reckoning of the public good.

Last year, during the IPS conference at which Dr. Jacob Koh had delivered that formidable and memorable speech, she had run into her ex-classmate Jasvinder. Amy had heard through the alumni grapevine that Jasvinder had studied law at university before discarding her promising legal career to work at a non-profit, one of those activist groups to do with migrant workers’ rights. Amy thinks with embarrassment of the remark Jas had made, something about corridors of power, about how she hadn’t seen such a racially homogeneous group since her corporate days. This had unsettled Amy, as had the look that flashed across Jasvinder’s face when Amy had explained, “I’m here to learn about race relations so we can more effectively regulate media.” Disgust, quickly schooled into a flat and stony ambivalence. For the rest of the conference, Amy had sat quietly amongst the audience, uncomfortably conscious of the emotions percolating inside her: anger and discomfort. Conscious of the fact that what Jasvinder had said was true: most of the speakers, if not most of the audience, had been, like her, Chinese. This feeling, not unlike the faint sorrowing shiver of unease that had washed through her upon reaching the conclusion of the play, had lasted for the rest of the day, until she had returned to the office and settled back in her cubicle amongst the other entry- to mid-level executives at the civil service. No, Amy decides, she must have misunderstood that look, and even if she hadn’t—it doesn’t matter. The work she does matters. The work of judicious redactions and classifications in the public interest, for the public who must not be unsettled, who cannot be trusted to sit with unsettling feelings that might at any moment flame into, to quote Dr. Jacob Koh, chauvinistic mutiny, the race riots of the not-so-long-ago past that passes for a history in this country—that is what really matters. In this belief, she is buttressed by the edifice, imposing and entire, of the civil service.

This, she knows.

*

The play knows what it is about.

The play knows what it is about, which includes the things that the playwright knows it is about and in fact deliberately put there, the things that the playwright does not know it is about and put there but subconsciously, and the things that the playwright did not put in there at all.

For the play does not exist only in the black marks writhing on a white rectangle that is an image, a projec

tion of light. The play exists in

words spoken

the sweat of Devan who is not Devan at all

(he is Tree #3 except that trees do not sweat

but only

respire

)

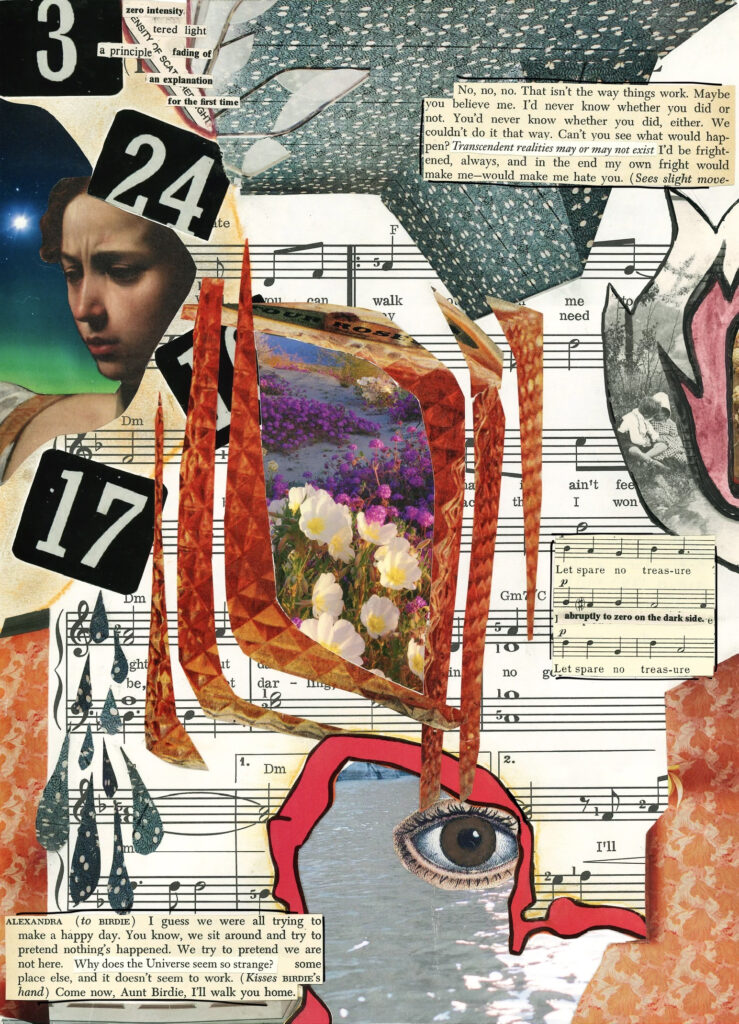

the fabric backdrop painted & pinned by Jia

the black box of the theater stage

& long-forgotten, a memory of torches

of real fire

that burned bright in a production of Titus Andronicus, as seen by the playwright ten years ago at the Globe in London

which is a city,

in a country,

that once colonized amongst others

this country

& made it “ a country ”

& started the processes we see dramatized

here

Fake blood, real fire.

Fake trees, real water.

[

TREE NO. 3. What will you miss?

TREE NO. 2. Nothing, ‘cause I’ll be dead.

TREE NO. 3. From under the poured concrete, I think, my roots will remember, I’ll miss—

]

[

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

]

PLAYWRIGHT. (outraged, in Singlish) Like that also must cut?!

PRODUCER. It’s that or accept the R21 classification.

PLAYWRIGHT This is ridiculous. They’re TREES, for God’s sake.

PRODUCER. Male-coded trees.

birdsong

orisons

the long call

tree light

filtered by, streaming through

(the gaps in) our canopy

stridulations of cardiodactylus singapura

The play’s the thing, the play at the end of the world, a play

of water

the susurrus of trees

a murmur of mother’s milk

& resin & sap

these are the things the playwright knows as well as does not know.

his distance from women

the loss of indigeneity

Here we are at the end of everything.

the breeze of green lungs

that must reach for a last gasp

before they still—

the air on what promises to be a hot day, heavy & shimmering

DIRECTIONS. Their last words said, the trees cease to speak. Dawn comes. The cicadas sing, the birds chirp and chirp and chirp. Then all fly away, their dawn chorus growing increasingly dissonant, yet increasingly distant, before silencing altogether. From the same distance yet growing ever nearer, the unintelligible sound of men’s voices, the buzz of a chainsaw.

END.