Prunus Alleghaniensis

Christina Craigo

Lillian

Twenty-seven of my forty-six years. But only one or two with any air in them. Flowers and clean linens. He was so tall he could lift me up into the sky like I was a little bird. He handled me like one, then. Always laughing.

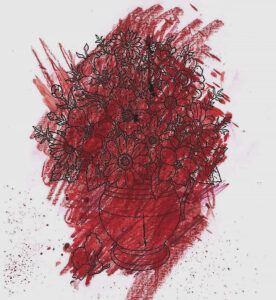

Then eight children. So many sows and hens, so many pans of cornbread, pots of green beans and pinto beans, pans of biscuits, jars of plum jelly, went into them kids. And into the six feet eight inches of Hiram. And there was sewing, and diapers, and wash, and wash, and wash. I got along as well as most women with my babies, but I could never make enough, or clean enough, or do enough. Then our youngest died, and then our eldest. The anguish of it, and Hiram not able to cry and so not ever able to laugh again neither.

For some reason, Otmer wanted to talk to me on my own. For some reason, he wanted to touch my face, and then my neck. It didn’t mean nothing to me. Only it was like water. Like a deep drink of cold water after years of drought. I closed my eyes.

Hiram opened the door when we was standing there by the table just like that. Just a hand on a neck. But there was no story to be told about such a thing. Somehow Otmer got around Hiram as he lunged. Hiram is strong as a bull, but Otmer outrun him without no trouble.

Hiram didn’t lay a hand on me, but he broke the table in two. And then after thinking on it a while, he broke the two pieces all to bits. Broke the churn my mother give me, and a lot of the dishes. After a while he quietened down. His gun was right there in the corner, and I thought he would use it, and I thought that would be all right.

He got up in the morning and left, didn’t say nothing to me, and the children come down from the shed. I give them walnuts and apples and sent them on to school. They was a quarter mile away when I remembered Petunia, poor girl. I milked her, poured the milk into a clean crock, and put it in the root cellar where the kids would know to look for it. I rinsed the pail at the pump, and I fed the chickens. Put the eggs in a little sack with Mamaw’s ring. Then I set down on the bed and et a wrinkly apple myself. Last one, I think. I picked all I could off of Mom’s old place, and doled them out the whole winter.

The places up here on the tops of the mountains have names like “Liberty,” but it looks to me like the towns down beside the river would give a person more freedom.

I made sure Junie’s cat was out, and I opened the window. I lit the stove, turned the flame low, and walked out. I crossed the porch and set the sack down on the bottom step, and I took my apron off. Wadded it up and looked at it. I’d slept in that, or tried to, in Junie’s bed. Flimsy wall between me and Hiram as he snored. I threw it in through the open window onto the stove.

Oh, those first flames. They made such a satisfying sound.

I watched the fire from up behind the shed. Simon, our boy who was done married, come along when there wasn’t nothing left but a rocking chair on a scrap of porch. He picked it up and threw it in the flames. Then he raised his head slowly until his eyes met mine.

June

I saw Otmer Davis going up the hill toward our place, on Shanks’ pony, so I followed him. Sometimes—not every time—he came with pockets full of candy from Hank’s store.

By the time I made it to the house, Daddy was there, opening the door. He must have come down from the mine just then.

He went in, and Otmer came tearing out. Daddy followed him onto the porch, lazy, and just leaned against the post. He spat once as he watched him go. There was no sound except Otmer’s shoes hitting the ground.

Then Daddy turned around slow and went back in. He closed the door so nice and quiet, I was surprised to hear a lot of loud noises after that. But there was no yelling. It wasn’t like over at Ruby’s place when there’s a fight.

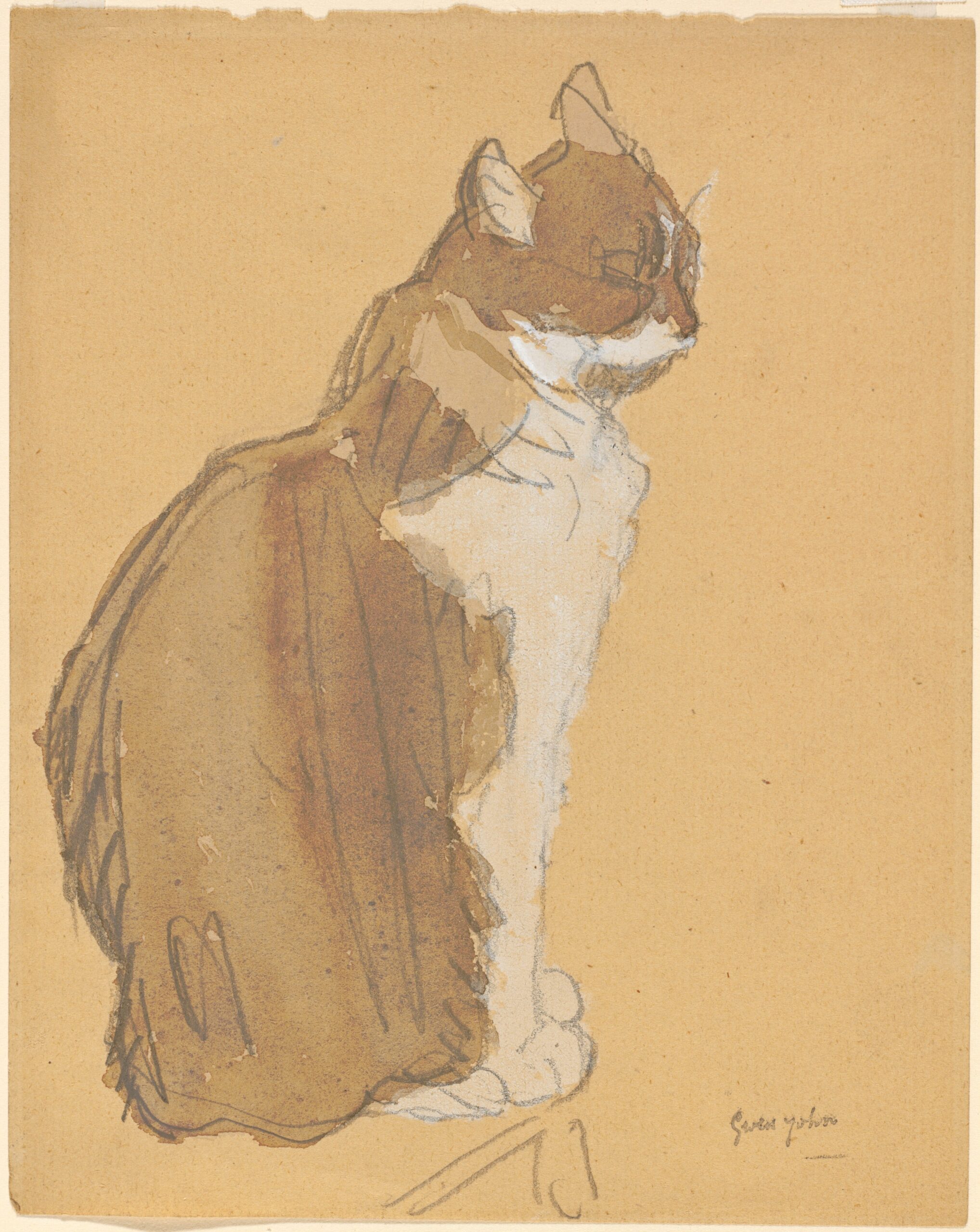

Nimrod came and slunk around my ankles then, so I picked him up. “Please issue your report, sir. What have you concluded, sir? Hm?” He gave no answer. I kissed his head and put him on the lowest branch of the little tree in front of the house. He loves to be there when the flowers come out, but they haven’t yet.

After a time, I went to the door and knocked on it, and everything got still.

“Mama?” I called.

At first she didn’t answer, so I thought she must be dead. Was this what it felt like to have a dead mother? The breathless, hard listening? The dread? I wanted to tell Nimrod the news right away, but he had wandered off.

Then I heard, “June? You go on over to Simon’s house.” There was a pause, and then, “Dessie has a new lamb, remember? She wants to show it to you.” It was true—Dessie and Simon did have a new lamb.

“Yes ma’am,” I answered, as if all this was right natural, and I clomped off the porch.

But I went off and sat by the root cellar, so I could listen some more. Nimrod came along.

“Be quiet, sir,” I whispered to him.

The problem was, I was so quiet that I got drowsy there in the sun. I waited to hear something awful happening, but I never heard it. I leaned my head against the cellar door, and Nimrod curled around me and purred.

When I woke up, it was coming on dark, and everything was chilly and dead quiet. I went to the door, and again I felt the dread, but I opened it. Something had happened to the table.

They must all have gone to Simon’s and Dessie’s. They must all have been looking for me, even Martin and Tommy.

I liked it—being alone, being mysterious. I decided not to go anywhere.

I found some walnuts and apples, and that’s what I had for my dinner. I took the enamel cup off its hook and pumped it full of cold water and drank it. Then I read to Nimrod about thinly clad children on a canal gilded with sunlight. He didn’t make fun about me saying those words out loud.

After a while, Daddy came home. His face looked different. He smelled different—like lamp oil, or maybe vinegar. He told me to go on to bed, so I minded him. I went to the outhouse, and I went into the back room, and I changed into my nightgown. I wondered about Mama and my brothers, but I was so, so tired, somehow. When Daddy started to snore, I just listened to that familiar sound, and it carried me off.

I woke up once. I peed in the pot, and slid it back under the bed, and then I was asleep again. In the morning, Daddy was gone. I took care of the chamber pot, and washed my face and hands at the pump. It was so much harder without Tommy or Martin or Mama. I had to pump with one hand and clean with the other.

I almost started to cry, about the pump.

I decided I ought to get some eggs for my breakfast before going to school. I went to the hen house with the basket Mama always used. I threw some seed down to distract the chickens, and then I stole their eggs, all of them. I felt bad for the hens, losing more babies. But I carried the eggs back to the house and carefully lit the stove, the way I’d seen Mama do.

It was no time ‘til the basket caught fire. I didn’t know what to do to put it out. I never saw that happen before.

I called for Nimrod, but he didn’t come. I gathered up my four books and my Sunday dress, and I ran out. The flames seemed to rise up fast after that. Petunia was crying about it. Simon came when it was burning good. He gathered me up into his arms (even though I’m too big for that) and we watched it together. Then he put me down and went over to throw Mama’s rocker onto the fire.

“Oh, Junebug,” he said mournfully, as it burned.

Hiram

I’d of killed him if I’d of caught him. The shame of it. The stench of it.

When I come to my house there was a man touching my wife. His hand was inside the collar of her blouse, and her head was leaned back, and her face was like something out of one of those pictures Saul keeps in his coat pocket. The shame. His hand inside her blouse. In my house. I’d’ve killed him if I could. How many other times, how many other men.

I only followed him out to the road. When he was off my land I stopped and watched him. The devil. He run into the brush over on the Harmons’ property and out of sight.

And I did not beat her. But only because she was out of my reach. I don’t know where she run off to while I went after Otmer. The children never come neither. They needn’t’ve been afraid of me, but in truth, I thought about killing Lillian all night long. Otmer too. Problem is, that would let them off easy. I’d still be here suffering. In the pen. With the shame. Everyone from here to Ohio would know about my shame.

In my mind, I studied each of the children’s faces, and I decided they was mine. Had to.

The sun come up, and I made coffee. It reminded me of the cow, so I went and milked her. I took the eggs from the hen house and I fried them all, thinking the children might come. But they didn’t, so I had all of them, and coffee and all the milk I wanted, for my breakfast. Might of been the first time in my life I et my fill.

It’d been 27 years since I fried my own eggs. More, even—I hadn’t fried eggs since Mother laid in bed for a month after Dad died. It wasn’t no trouble though.

I got down on my knees beside the table, right where Otmer had been, and I had a talk with my Maker. I asked him to forgive me for my murderous thoughts. I promised the Lord I would not kill Otmer, nor Lillian neither. I promised the Lord I would not even let it be known that she was guilty of adultery. But I did not promise Him that I would shelter her.

When I finished my prayer, I washed my face and changed into my Sunday clothes. I got Lillian’s Daddy’s Bible down off the shelf and put it out in the yard under the plum tree, with June’s doll and Martin’s gun and Tommy’s fiddle, and half the money from the covered dish. The sun was shining brightly that spring morning. The dew sparkled all around as I put my own gun into the shed.

I poured the kerosene onto the table slowly, so it’d soak in good. After I tossed the match in through the open door, I went up into the woods a piece where I could look down and watch the house burn. It was good. It had a good clean smell to it.

Simon, my eldest boy living, come along then, and seen the house. It was gone; too late to do anything for it. The rocking chair on the porch was the only thing left. So he threw it in where it could burn better.

He looked up the hill, scanning. “Dad?” he called out. But I didn’t answer him.

#