Automat

by Sarah Kosch

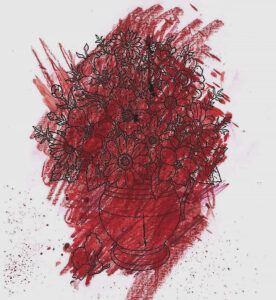

At least the Cadenzas are lovely, their deep red petals folding around each other like children with secret toads and moths clutched within their hands. There are gnats hovering; the sun is beginning to sink. Mrs. Aust is angry that her husband hasn’t come looking for her yet, raw at the thought of him, and hoping all the same. She isn’t sure what she expects him to do, only wishes for something surprising. He is often a lout but she doesn’t often lose her temper like this.

She examines some creeping blossoms called Belinda’s Way according to the wooden sign planted in the soil. There have been other strange names as well—Sunsprite, Ispahan, Princess Alexandria—and she wonders whose job this is, this naming. How did they acquire such a duty? Not every gardener is a poet. Neither is she for that matter, but she would volunteer to help if they could use her. Bum Kipper. Sexton Away. Sodden Earth.

The mud sticks to her tennis shoes, but they’ve always been ugly. Practical shoes usually are. She plods on down the path, touching flowers, reading signs. It’s still humid, no relief after the storm, the air just sweating right along with her, her skivvies twisting up uncomfortably beneath her slacks. There’s nothing sexy about it. No wonder Mr. Aust has grown so cynical. She’s hardened too, and softened, all in the wrong places—thick-armed, thick-waisted, thick-breasted—uncomfortable baggage, irreparably stretched. She tries not to think about it.

Today was supposed to be nice. An hour’s drive. You’ll love it, said their oldest. We took the kids last weekend. Mrs. Aust can’t imagine taking children to an art museum. All that white. All those sharp edges. All the parts that are her favorite. The open space, the high ceilings, the quiet. The museum’s rose garden is quiet too. The heat must have scared off the rest of the walkers, or they’ve already gone home. She’s not sure of the time. She forgot to wear her watch and is dismayed every time she checks her naked wrist.

A pond borders the garden, and she crosses the path towards it, hoping for calm blue ripples and bullfrogs. But when she looks closer she can smell it, the stagnant water scummed over with lime batter. A fountain pokes out in the center, turned off, just a useless spout of metal pointing up at the sky, rusting. Sweat drips into her eyes and stings enough that she has to take her glasses off to rub at them.

Today was supposed to be nice, and it’s not. She isn’t sure why it all went wrong. Maybe the heat. Maybe the fact that Mr. Aust would argue just for the hell of it that it’s been hotter. Telling her to bring her jacket even though she was sweating, because God knows, he’d hear about it when the air conditioning was on too high. And it had been, a little, though she wouldn’t admit it to him. And anyway, it would be absurd to have on another layer now, back outside in the rose garden. It’s that global warming, she thinks, fanning herself with her Art Center brochure and feeling the sweat slipping from her hairline. All that stuffy science coming back to bite the world right in the rear end.

Like Mr. Aust’s, leaning over his cane to examine that enormous egg-shaped cavity carved in stone outside the museum entrance when they arrived.

Would you look at that curve.

It’s a little saggy at the bottom, don’t you think? She couldn’t resist. She had watched him straighten and hike his khakis up. A little brother and sister had whizzed past them then, scrambling up the front of the sculpture, hoisting themselves over the edge and running their hands over the smooth back wall. There were the parents of course. She remembered how it was: Mom standing close enough to catch them, repeating careful to unreceptive ears; Dad with the camera, his daughter smiling so wide her eyes shut tight while her brother rubbed at the walls, staring at the stone like it was a magic lamp about to spurt a genie. It’s hatching! and the two of them took off again, running down the path as their parents meandered behind holding hands.

Mrs. Aust doesn’t carry her camera anymore—it’s just one more thing to keep track of—and she certainly doesn’t hold hands with Mr. Aust—if one of them goes down, both of them will go down. In the garden now, she wishes she still did. The trellises and rows are green and rambling, thick like something haunted, the blossoms impervious to the wilting heat. It’d be nice to share it with someone. But her husband is nowhere in sight. She wonders if he just went back to the car, if he’s waiting for her there, but she is not going to go look. She is going to wander in the garden until he makes an effort. After fifty-three years of marriage he should know that she’ll out-stubborn him every time.

This was supposed to be nice. An adventure. He didn’t need to be crass, ogling Female Nudes 1, 2, 3, and 4. The surrealists make it too hard to tell what I’m looking at. He didn’t need to be cruel.

Is my hair all right? It had been a little windy coming in and she was worried she was walking around looking foolish.

What hair. He laughed after, like he was joking, but it felt sharp.

She pats her hair now, fluffy white curls like cotton on her head, thinning yes, but still covering what it should. She’s been thinking of growing it out but can’t decide.

Mr. Aust can be so thoughtless—decades of married life, two babies, and three grandbabies, and still a child himself. It relieves and irritates her, that big, bald, immobilized toddler, one minute throwing a tantrum and the next grinning and winking from behind the sofa. To never grow up—but someone has to do it, don’t they?

If it were just her, things could be different. She could have been a flower-namer. Owned a bakery. Maybe learned French. Wipe your feet, see voo play. A little shop in Paris. Vacations in Barcelona. She is glad the kids don’t get married so young anymore, but jealous too. Who could she have been? A world traveler, a sled dog driver, a pilot—but then again, they aren’t necessarily any more adventurous these days either. There’s never enough time or money. Too much to get out of the way first.

Still, it’s nice to believe in magic. A rose garden housing the fountain of youth. A time machine. She’d go back to the night he proposed, the end of summer with a hint of fall in the breeze as they rode the Ferris wheel at the county fair; she’d tell him to get stuffed and then jump on the next train to the west coast. She still hadn’t seen the Pacific besides pictures. She’d strip her clothes right off and dive into those blue diamonds, free and slick and uncatchable.

She shakes her head and tries to focus. It’s been a long day, and long days get her winded, get her head fogged up with all sorts of nonsensical bits. Her husband is probably waiting in the car. He’ll be mad she stormed off, but what was she supposed to do? What hair? Hadn’t he seen the way it heated her up inside? Made her eyes water? No, he couldn’t take his eyes off some big-titted floozy leering from her frame. He’s been bald for years and she’s still loved his softened, gray edges. Was it too much to ask that he’d still like hers? She feels like crying and being swallowed up beneath that scummy green pond even though she knows it is silly, that she is silly, that he and it and this whole shebang are ridiculous.

She should sit down. Collect herself. She looks back the way she came, hoping for a bench along the side of the path, but the shadows are thickening beneath the trees and the fireflies are beginning to blink. If it gets too dark, she won’t be able to find her way, and she’d rather not spend the night in the dank mud. Mr. Aust will certainly never find her now, and she will settle for giving him the cold shoulder on the drive home.

She retraces her steps, and eventually cracked gray stones begin to emerge from the mud. Up ahead is the entryway, and just like that she’s out the garden and back to a life of trimmed lawns and parking lots. Lights still shine from the museum windows, and tall lamp posts lean over the pavement like intermittent sentinels. For a moment, she’s disoriented, unsure which way to go. The windshields of a handful of cars reflect the lamplight, but no headlights are on. She wonders about the time, about where Mr. Aust has gotten to. She checks her naked wrist and sighs, decides she’ll just have to go back to the museum and get things sorted.

She tries the first door she comes to and it is still unlocked, but there is no one wandering the white rooms. Cutting across the Surrealists, she realizes she doesn’t know which direction the lobby is. The white rooms open to each other, circling, empty, brightly-lit tunnels. She feels so tired. The bench in the next room is too inviting to pass up. Her achy joints collapse onto it, and she stretches out her sore legs. She’s ready for bed, can’t even imagine staying awake for the drive home. Maybe she’ll just sleep here, sprawled out under the painted eyes surrounding her. She can provide some entertainment, snoring and jerking and mumbling during the dark hours when the people in the paintings would have had only each others’ frozen forms for company.

The painting on the wall in front of her makes her even more tired, the dull paint reminding her of too-bright lights and burnt coffee when everyone else is asleep. The woman in it could certainly use a laugh. She looks as cross as Mrs. Aust feels, or felt—sleepiness dilutes the sharpness of it. Now she just wants to know where Mr. Aust is.

The mud caked on her shoes has dried, and there’s a trail of dirt crumbles intruding on the polished wood floors.

“Well, shoot,” she says out loud.

“Hello?” A man with salt and pepper hair and a vest over his white-collared shirt peeks around the corner. “Where did you come from?” He is wearing a laminated badge pinned next to his tie.

“I snuck in the back,” she says.

“Well, we’re closed. It’s time to go.”

“I wondered,” she says. “It feels late. But I lost my husband.”

“Why don’t we wander out front together and see if we can find him?”

“Could you give me a minute? Now that I’ve sat down, I’m not sure I can get up again.”

The man smiles. “Sure. You rest here. I’ll go talk with reception. What’s your husband’s name?”

“Gerry Aust.”

“I’ll be right back.”

“Thank you; I’ll be here,” she says. “Oh, and sir?” She points to the painting. “Is that woman supposed to be anyone in particular?”

“The artist’s wife was the model,” he says. “Though I heard he painted her to look younger and thinner than she actually was.”

“Of course he did,” she sighs and turns back to her glum new friend. She listens to the squeak of the man’s shoes fade from earshot.

Only the artist’s name is listed on the placard. 1882-1967. Her body. His grave. Mrs. Aust shivers; the air conditioning is still on at full blast. Her body feels as heavy as if it’s been filled with sand, and it’s hard to keep her eyes open. She fights it. How embarrassing if the man comes back—or Mr. Aust comes back—and she is asleep like a naughty child snuck out of bed.

She tries to rouse herself, shifting and pinching the inside of her elbows, sitting up straight like the woman in the painting, who sits in front of a window, the sheen of glass separating her from the blackness outside. A row of lights—real or reflections? Mrs. Aust isn’t sure—trails off at the top of the canvas. The woman sits alone, safe from the dark, dark endless night, safe clutching her midnight coffee, one glove off to feel the slickness of the mug, the solidness to keep her there, keep her steady, keep her focused. For what? It could slip. It could shatter. She took off one glove, but skin isn’t always more trustworthy when it’s exposed. She shivers in her thick green coat, tugs at the edge of her hat, keeps her eyes down. It’s late; she’s alone. What happens next?

And Mrs. Aust seems to know what happens next. It’s like she was there that night too, eating a nickel’s worth of sandwich, reading the paper. You always had to look your best. You never knew who was watching. This woman knew a painter. This woman screwed a painter. Artists are selfish lovers. Mrs. Aust doesn’t know from experience, but she has a good imagination and she’s heard how these things go.

Someone is tapping out a rhythm for her thoughts. Drum beats. A ritual by firelight. A funeral march. Goose pimples prickle her skin.

“Cee Cee?”

She can see her husband’s bobbing form reflected in the glass, his cane tapping up the floor behind her, but she doesn’t turn around. She can’t. He is part of the painting now. She married a businessman, and he was only a selfish lover sometimes. Now he wasn’t a lover at all, just a staple of the house, a slipcover, a bar of soap, there and not noticed until he’d run out. She sees him at the end of that dark, dark tunnel, or are they reflections? Are those lights inside or out? In the sky, against the back wall, whichever—in that darkness, there he is laid out, unrecognizable and dead. She and the woman will live on alone, daintily holding their crockery, drinking coffee when they can’t sleep.

“I’ve been looking all over for you.” He stands next to her now. “You had me worried.” She’s in the painting too, she notices, hurt and cold and afraid. “I’m sorry. For whatever idiot thing I did this time. I’m sorry. I didn’t mean it.”

He didn’t. She knows that. He’s always joked about the things that scare him most. This thinning out, bodies turning to glass. It snuck up on them. All in all, her husband was a good man, is a good man; she catches herself. It could be soon that he makes that switch, that he steps off the platform, that he passes out of the field of view, mark-less, effortless, clean. And she will miss him so much when he does. She knows that.

She takes his elbow in her hands, feels the rightness of the joint, the softness of his shirt. Those beautiful blue eyes—where has the time gone? There’s no turning back now. Now, no matter if she likes it or not, today or tomorrow, it’s the two of them trudging onward together, elbow to elbow, shaky bone on shaky bone, and she loves him. She’ll love him for it all, again, and again, and again, like she’s decided a hundred times before.

He wraps an arm around her shivering torso.

“I told you to bring your jacket,” he says.

“I know,” she says. “I know.”