Just Beyond the Tree Line

Jesse Millner

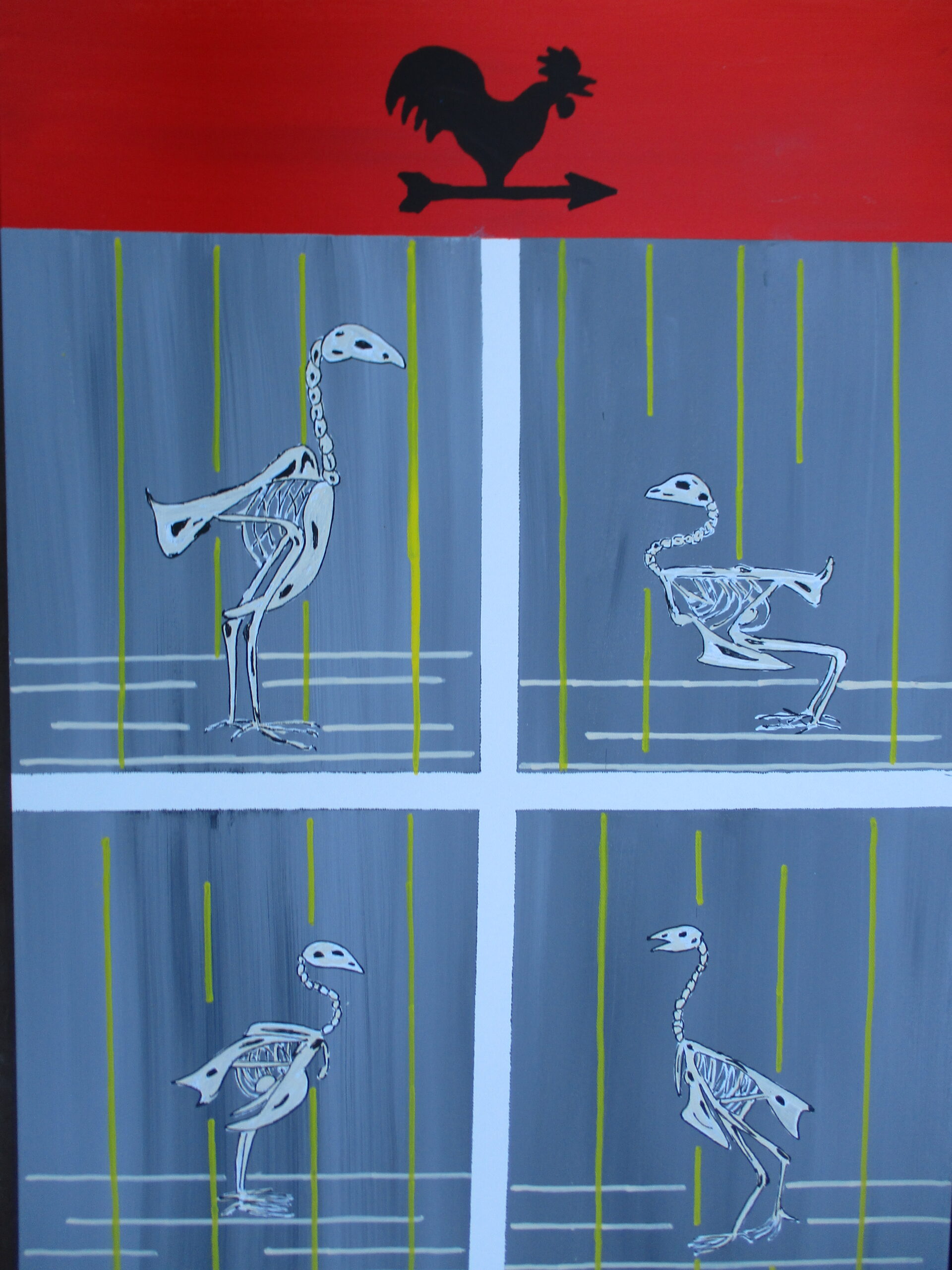

When my grandpa shot a hog or when Grandma broke a chicken’s neck, I was always somewhere else—playing with plastic soldiers in the yard, looking for arrowheads in the woods, or curled up in some sunny place on the front porch reading a book. I never thought much about the hams curing in the smokehouse being the flesh of the actual creatures I’d fed with the slop jar on warm evenings when the crickets were louder than what I should have been thinking about: How everything is connected somehow—animals, people, pigsties, chicken coops, trees—how everything is part and parcel of the animated spirit, the ghost cloud inhabiting every stone and every breathing creature, every stick of wood, every pore in every inch of human flesh, which in the end will be not be sacrificed like the hog or a chicken, like the deer or squirrel or slowest rabbit. Instead, there will be, for most of us, time for reckoning, time to consider the dark that waits for us just beyond the tree line, where in memory, branches whisper just a little—barely audible sighs in the forest near the farmhouse where long acres of skin slough off onto our sheets each night, our beds accumulating the detritus of our bodies, until we are no longer our bodies.

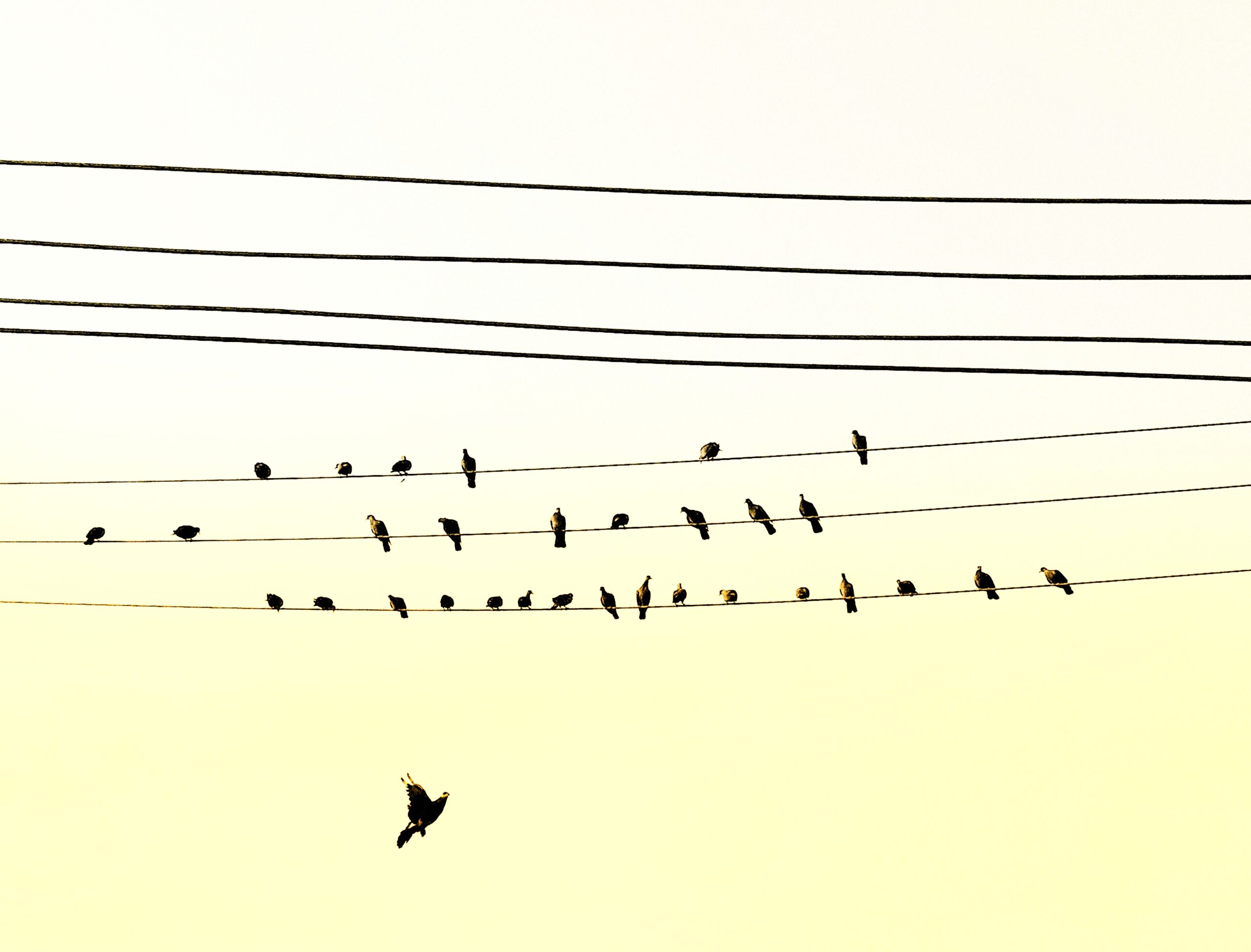

Perhaps we’ll wake up in a railroad station with windows full of the blue skies and cumuli of another destination where many tracks lead toward happier places, where a loudspeaker calls out the names of towns, which is followed by the echoes of thrumming feet and the hushed voices of travelers who are already dreaming of cozy living rooms with blazing fireplaces beyond the journey past miles of frozen fields yielding to forests where the silence falls down from the trees like the dead leaves of an autumn’s perfect sorrow.