Allison Field Bell

Gum

He leaves his gum all over the house. I don’t know when it started, but I know it’s worse than before. I go to brush my teeth and there it is: a white ball of chewed nicotine gum, still tacky but hardened. I find myself pinching each little ball, holding it between my thumb and pointer finger, walking to the trash can to deposit it. I wash my hands thoroughly after. Though he is my lover. There is no telling what edge of intimacy repulses me. Gum. Just yesterday, I found one under the couch. Like a giant pus-filled pimple. It was hard as small rock though, and not at all sticky. Still: my routine, the walk to the trash can, the washing of hands after, the fury as I turn the water to scalding. I usually yell at him then. I tell him it’s disgusting and can he just throw his goddamn gum away? He’s a conscientious consumer, always saving plastic bags from loaves of bread and tortillas. Embracing the notion of reuse with a bit too much commitment. The gum, he says, he plans to chew later. But inevitably he forgets. He leaves it on the container of my face lotion, at the edge of the tub, on our end table, our coffee table, our dining room table. I think about how to make a point, and I think I might start collecting them into a box. A whole shoebox full of his mistakes. Something tangible to show him. This is how you have wronged me, I might say. And how many times do I need to pluck gum from an object to fill a shoebox? I wonder how many years it will take for me to make my point. How much gum he will have chewed and rolled and left for me to find. And will the point be well-received? Here, I might say, this is our relationship in a shoebox. Our personalities. The gum, the shoebox, the collection of it. I am a collector, and he is forgetful. Always losing his keys and his wallet. I’ve been told I am too rigid in my expectations. I’ve been told: relax, take it easy. No need to check the stove five times, the lock on the front door at least three. Except then he leaves a burner on all day. A gas stove. A live flame. It is difficult for me to understand leaving. Leaving the stove on, leaving a wallet or keys not in their place, leaving the gum here and there. Perhaps, I need to be more assertive. I will not pick up this gum, I might say to myself. His gum, his duty to retrieve it. And yet, what if we have guests or it winds up somehow in my hair? I will pick up the gum. I will collect it into a shoebox. I will tell him this is how I love him. This is how I hate him. This is the way I feel when I have to clean up his messes. Collect the feeling into a box, let it fester and form one giant glob. Then hand it back to him. Show him. Make him see that every little piece counts.

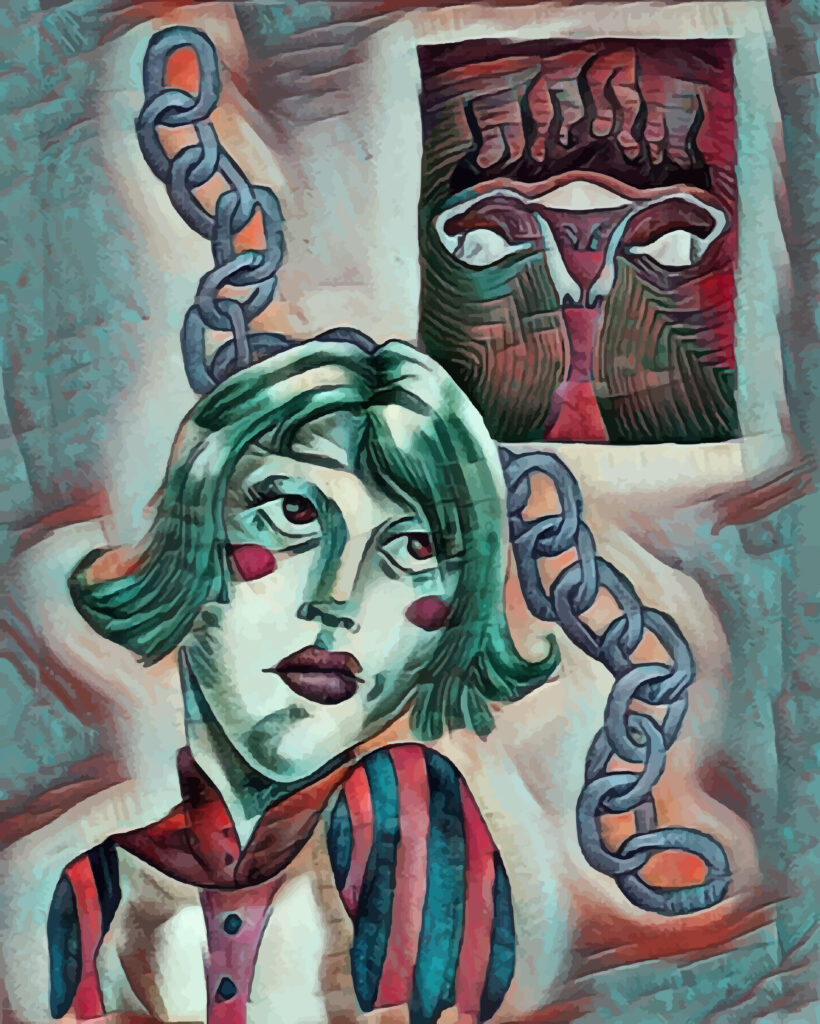

Anything to Mess it Up

It’s his. She hasn’t been with anyone else. Not even that one night when the surfer with the long sandy hair hit on her and she wanted to. She wanted to see him beneath her, writhing in pleasure. But she’s loyal in body if not in mind. Is this punishment for that? Her desire. She’s at a stoplight in San Luis Obispo, a city she hates for its sterile streets. Its street signs in a font called Libra. The whole place like a painting that’s too perfect: she wants to smear dogshit on a sidewalk, leave a coke can on a windowsill. Anything to mess it up. She’s feeling particularly angry at it today: all of its blondes strutting across pavement in miniskirts. She imagines each woman and the ways in which that woman is not like her. Sitting in the car at a stoplight, his baby in her belly. Knowing that she’ll have to be rid of it. Knowing that she loves it already. The idea of them together. All three. But she’s twenty, and she doesn’t want to be a mother. Not now. Not when she has so much life on the horizon. She’ll go to Baja and surf the waves of the Pacific there. Or maybe she’ll go to France. Sit along the Seine with a baguette and a bottle of Sancerre. She doesn’t have money for either, but the thought is nice. And here at the stoplight, she’s rubbing her belly, imagining the tiny fetus: not human, but a seedling for a human. His denial was the worst part. He’s Catholic, not devout, but Catholic enough. She knows what she needs to do, wants to do. He’s already said he won’t drive her. Cheating slut is how he said it. Now she needs his forgiveness for this thing in her body. Forgiveness for the fact of her body. A woman with a womb. When she called to make the appointment, the receptionist on the phone warned her of protesters. And at first, she couldn’t understand. Molesters? No, she said, it was consensual. The receptionist on the phone said the word again. Protesters. She had felt her body heavy then—like a weight on her chest driving her into the earth. Protesters. The procedure was scheduled for the following week. She found a friend to drive her. A woman. She doesn’t want any mistakes to be made. A nurse asking, Are you the other creator of this fetus? Do nurses ask that? In a hospital, nurses use the word father. But a father implies a child, and this is a fetus. She’s a liberal after all. She believes in choice. Her choice: to think of this sometimes as a fetus, sometimes as a baby. Because it is her body and what her body has made. The protesters will see it differently. She imagines men: a whole crowd of them. Bloody signs and yelling. She imagines an old woman, retired and in a sun hat. A woman she might help with groceries at the Whole Foods. But here the woman is a nasty piece of work. At the stoplight, she watches the red stay red. She thinks of that little test, the way it changed. The way she returned to the store and bought a half dozen. All positive. Outside her window is a palm tree. She hates palm trees. They’re the Barbie dolls of trees. Smooth sleek trunks with their flawless fanning of leaves. Outside the window, the sky is a rigid blue. Not even a cloud. She should be headed to the beach, bikini and beach towel in the backseat. Instead, she’s at a stoplight, and the light turns green and the car behind her honks. And she stays put, foot on the brake. The car honks and honks, and she stares forward at the little block of gorgeous storefronts, at the glare of sun on glass, at the clear and sparkling sidewalks. The car honks, and she sits there waiting, not wanting to change the moment, choosing to stay still.