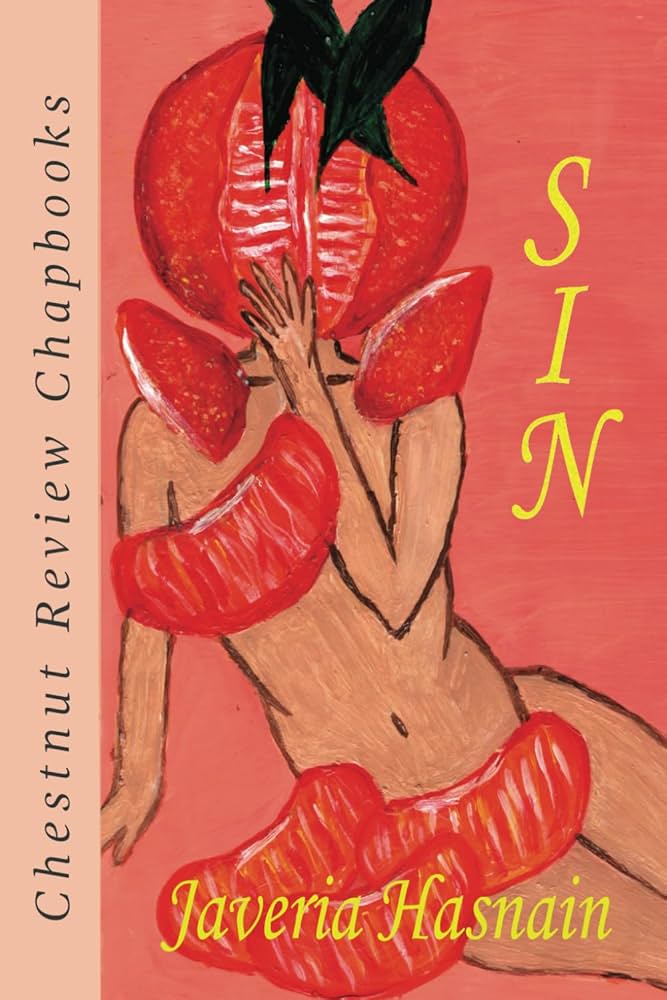

“I Write for My Beloveds”: An Interview with Javeria Hasnain

Javeria Hasnain is a poet, translator, and educator from Karachi, and the author of SIN (Chestnut Review, 2024). Her poetry and prose have appeared widely, including in Pleiades, Poet Lore, Foglifter, beestung, and elsewhere. She has an MFA in Poetry from The New School, and has received fellowships and scholarships from Fulbright, Teachers & Writers, and Sewanee Writers Conference, among others.

Shlagha Borah (she/her) is from Assam, India. Her work appears in Poetry Northwest, Cincinnati Review, Salamander, and elsewhere. She received an MFA in Poetry from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville and is an Assistant Editor at The Offing. She’s a 2024 Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship finalist. Her work has been supported by Brooklyn Poets, The Hambidge Center, The Peter Bullough Foundation, VCCA, among others. She is the co-founder of Pink Freud, a student-led collective working towards making mental health accessible in India. Her work is available at www.shlaghaborah.com.

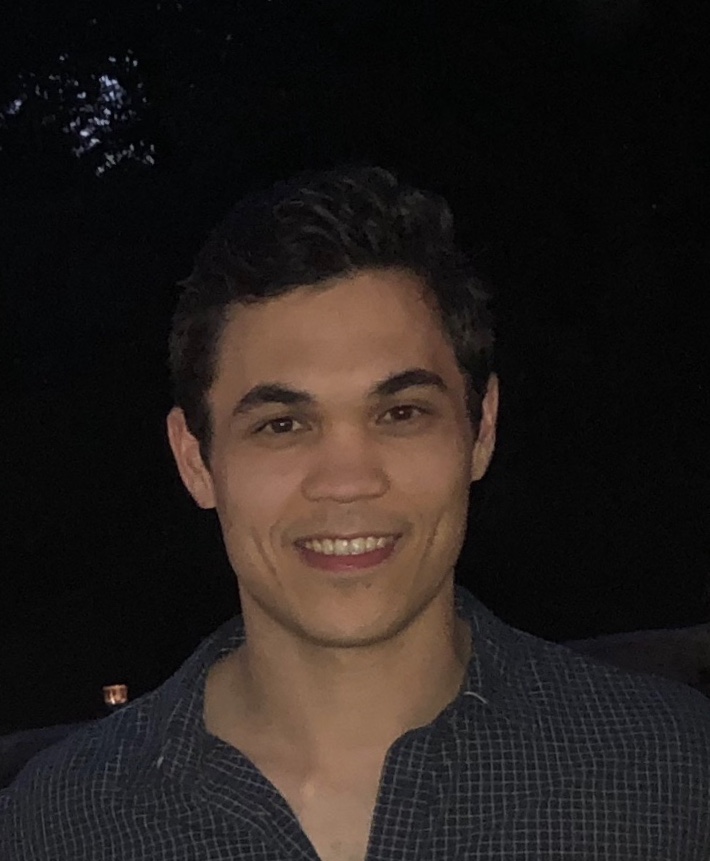

Risking the Hug: An Examination of Sentimentality and Sincerity in Lars and the Real Girl by Daniel Abiva Hunt

Daniel Abiva Hunt holds an MFA from the University of Houston. His stories and essays have appeared in New England Review, The Masters Review, CRAFT, Maine Review, Portland Review, and elsewhere. He is currently a PhD student at the University of Cincinnati, where he teaches and studies fiction.

Poetic Endings: Nailing Down the Threshold by Dia Calhoun and Deborah Bacharach

Deborah Bacharach (left photo) is the author of two full length poetry collections Shake & Tremor (Grayson Books, 2021) and After I Stop Lying (Cherry Grove Collections, 2015). Her poems, book reviews and essays have been published in Poetry Ireland Review, New Letters, Poet Lore and The Writer’s Chronicle among many others, and she has received a Pushcart prize honorable mention. She is currently a poetry reader for SWWIM and Whale Road Review and a mentor with PEN America. She lives in Seattle. Find out more about her at DeborahBacharach.com.

Dia Calhoun (right photo) is the author of seven young adult novels, including two verse novels, After the River the Sun and Eva of the Farm (Atheneum, 2013, 2012). She has won the Mythopoeic Fantasy Award; published poems and essays in The Nashville Review, The Writer’s Chronicle; EcoTheo Review; MORIA Literary Magazine; And Blue Will Rise Over Yellow: An International Poetry Anthology for Ukraine, and others. She co-founded readergirlz, recipient of The National Book Foundation Innovations in Reading Prize and taught creative writing at Seattle University and Stony Brook University. More at diacalhoun.com.

The Manananggal as Mythmaking by Melanie Manuel

Melanie H. Manuel is a Filipina American poet. She obtained her BA from UC Davis in English and Asian American Studies and is currently attending SDSU for her MFA in poetry. She is a recipient of the Prebys Creative Writing Scholarship, the Master’s Research Fellowship, and most recently, the Sarah B. Marsh-Rebelo Scholarship. She is the Production Editor for PIOnline and teaches in the Rhetoric and Writing Studies department. Her work has been published by Third Iris Zine and North American Review, and she has forthcoming work with minnesota review, Porkbelly Press, and Zone 3.

Delightfully Weird by Tommy Dean

Tommy Dean is the author of two flash fiction chapbooks Special Like the People on TV (Redbird Chapbooks, 2014) and Covenants (ELJ Editions, 2021), and a full flash collection, Hollows (Alternating Current Press 2022). He lives in Indiana where he currently is the Editor at Fractured Lit and Uncharted Magazine. A recipient of the 2019 Lascaux Prize in Short Fiction, his writing can be found in Best Microfiction 2019 and 2020, Best Small Fiction 2019 and 2022, Monkeybicycle, and numerous litmags. Find him at tommydeanwriter.com and on Twitter @TommyDeanWriter.

Wristwatches and Miniature Clocks by Daniel Abiva Hunt

Daniel Abiva Hunt is a writer from South Jersey. His stories and essays appear or are forthcoming in The Masters Review, CRAFT, The Maine Review, Portland Review, and elsewhere. He previously served as assistant fiction editor for Gulf Coast, and he is currently a PhD student at the University of Cincinnati, where he teaches and studies fiction.

On Reality, Fiction and Neurodiversity by Victoria Costello

Victoria Costello is a writer and teacher of memoir and auto-fiction based in Ashland, Oregon. Her debut novel, Orchid Child, forthcoming from Between the Lines Publishing in June, 2023, is based on the three-generation family story she first told in her memoir, A Lethal Inheritance (Prometheus Books/2012). As a science journalist, she’s written feature articles for Scientific American MIND, Psychology Today, Brain World, and Huffington Post. She earned an Emmy Award as a writer/producer of documentary films, including This Island Earth and Wolf Nation, shown on PBS, Discovery, and The Disney Channel. Themes of ancestry, neurodiversity, and mysticism reoccur in her latest writings and workshops. Visit her website, victoriacostelloauthor.com for contact info and to read more of her work.

“Where in the body do I begin”: Grass and Hunger in Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas by James Ciano

James Ciano holds an MFA from New York University, and has received support from the Vermont Studio Center and The Community of Writers. His poems have recently appeared in Southern Humanities Review, Quarterly West, and Nashville Review. Originally from New York, he lives in Los Angeles, California where he is currently a Provost Fellow at the University of Southern California, pursuing a PhD in Literature and Creative Writing.

This Is Not a Day at the Fair: On Poetry and PTSD by Jennifer Metsker

Jennifer Metsker’s poetry collection Hypergraphia and Other Failed Attempts at Paradise was published by New Issues Press. Her poetry has appeared in Beloit, Rhino, Birdfeast, Gulf Coast, The Cream City Review and other journals. Her audio poetry has been featured on the BBC Radio’s Short Cuts. She lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where she is the Writing Coordinator at the Stamps School of Art and Design.

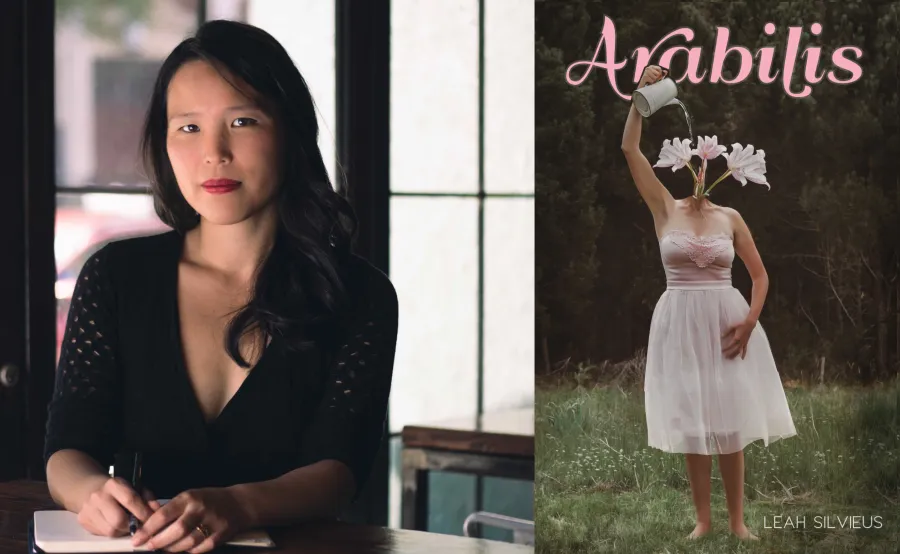

An Interview with Leah Silvieus | by Hope Fischbach

Leah Silvieus is the author of three poetry collections, most recently, Arabilis (Sundress Publications 2019), and is the co-editor with Lee Herrick of The World I Leave You: An Anthology of Asian American Poets on Faith and Spirit (Orison Books 2020). She is a Kundiman fellow, holds degrees from Whitworth University and the University of Miami, and is currently studying literature and religion at Yale Divinity School.