Some Notes on the Document After 11/8

by Susan Briante

1.

After the election, Farid and I renew our passports even though they won’t expire for months. We expedite their renewal, so they will arrive before the inauguration. We get our daughter her passport. We buy a home safe so that we can keep those documents in our house, drill holes in the floor of our bedroom closet so that we might sleep with our documents near us.

Farid is a US citizen. Farid is an immigrant. Farid has a Syrian name.

Farid applies for Global Entry status to expedite clearance at customs. He submits an on-line questionnaire. Customs officials interview him at the Tucson International Airport. He is fingerprinted. He is approved.

We realize that this is not an act of protest. We realize this is an act of relative privilege. We are anxious. Farid wants to have all of his documents in order, because this administration is moving the border.

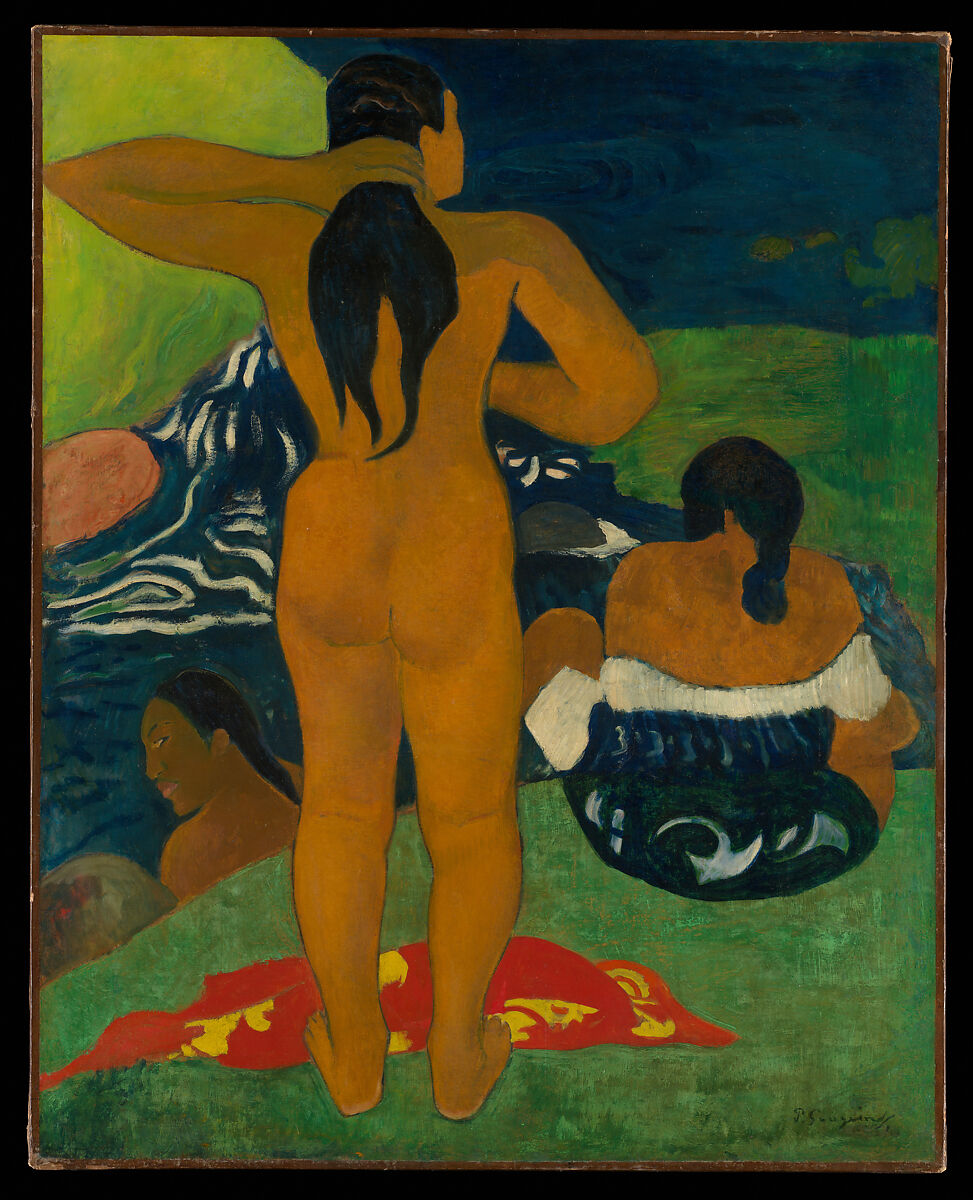

We are learning what happens to those who do not hold or have possession of the “correct” documents: at the traffic stop, at a public school, in the hospital waiting room. And we wonder: where does the deportee store her papers? In the plastic bag given to her by Homeland Security Department? What does the refugee carry in her pocket? Where does the immigrant, the exile, the asylum seeker maintain an archive of everything they had to leave?

2.

Moments after the inauguration, the Trump Administration removed pages related to climate change and LGBTQ issues from the White House website. In April, the Environmental Protection Agency followed suit removing all climate change information from its website in order to “reflect the approach of new leadership.”

In documentary studies classes, I teach students that the documents are never neutral, that the archive omits much more than it ever includes. In documentary studies classes, my students teach me as witnesses, historians, and writers. We teach each other that documentary writing must always demarcate the limits and biases of the document and the archive, their power and intent. We read the books of Claudia Rankine, Solmaz Sharif and Layli Long Soldier to learn how to push past those limits. We study the example of M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong!, a work that reconfigures (through cutting and manipulation) a legal document, which dispassionately recounts a massacre, to release the tragedy imprisoned in its words. We read Muriel Rukeyser’s “The Book of the Dead” in which she records a monument’s inscription then writes over it, contesting histories to correct monumental erasures. Angela Davis speaking at the Women’s March on Washington reminds us: “We recognize that we are collective agents of history and that history cannot be deleted like web pages.”

I teach students to question their documents as well as the limits of their perspectives. When considering the documents of migrants seeking entrance into the United States, I am aware of how often the United States government creates the conditions that force people to flee their homelands, yet still denies their entry into this country. I need to remind myself that the United States was founded on the ancestral lands of indigenous peoples, lands taken through murderous force and broken treaties, documents that lied or simply meant nothing, fickle documents.

Under each atrocity, another atrocity, as well as the documents that made it possible.

3.

Today more documents and more data are available to the poet than ever before.

Every one of our log-ins and every purchase we make, as well as each text, email, or photo we send becomes tangled in a very large net formed by ubiquitous information-sensing mobile devices, aerial sensory technologies, software logs, cameras, microphones, radio-frequency identification readers, and wireless sensor networks. A student of data collection and national security websites tells me every keystroke we enter into our computer or phone gets recorded at least eight times, stockpiled by governments and corporations. A tsunami-like tide of information rises.

In this swarm of uncontextualized information, we need to ask the questions: Who controls and who sees such data? Whose stories are privileged and whose are silenced? What narratives are being made up about us?

The President wants to see our documents. The Secretary of State wants to see our documents. The director of Homeland Security wants to see our documents.

Capitalism loves our documents. A lack of documentation can result in a lack of access to resources. A person without a credit history, without a history of debt, is considered a “thin file” and has little access to credit.

We need to take care of the archives that wittingly or unwittingly we create. At home Farid and I consult articles with titles like “A 70 Day Web Security Action Plan for Artists and Activists Under Siege.” He has left all social media accounts. He uses a secure email server, a new text messaging app, a service that scours the internet for the trafficking of personal information.

I send a scan of my driver’s license with certain information blocked out to Intelius group.

I call the customer service group at MyLife.com.

I wait to receive a text message code from Whitepages.com to confirm the removal of the record.

I follow the instructions on the “Control Your Information” option via the drop-down menu at the Radaris.

I am clear in my fear, in my plexiglass terror: the dream in which a Homeland security agent folds and stuffs a paperback book I ordered in 2006 from Amazon.com into my mouth.

What do we record? What should we erase? Every document, or lack of one, may or may not be used against us. At home, we consider this. We wonder what’s next for the archivist, for the documentarian, for the poet, who works with mirrors on her file cabinet, so she can see who walks in her office door, so she can see herself. At night we lay down in our bed in our house in the Sonoran desert, 72 miles from US-Mexico border on the ancestral lands of the Tohono O’odham. We listen the recorded sound of waves playing on a loop from our daughter’s bedroom. We wonder about truth. We sleep anxious next to our documents.