Grass

by Nicole Walker

It was late fall when you and I last met. Friends who only see each other once a year because continental drift inspires forlorn measurement. The cadence becomes dramatic. It isn’t meant to be. I only mean to ask, Or was it early spring? The grass was still winter-brown or becoming winter-brown. You would think the seasons would turn in concert with friendship, but instead, they turn against. I would like to Superman this world around. Bring on the Hoover Dam’s destruction. Bring back the Colorado River. Bring back the day we walked at Kennett River in Victoria, Australia, along the Great (Southern) Ocean Road beneath broad-leaved, evergreen trees. I mistook them for deciduous because I have lived too long in a pine forest that stays green even in winter. There, I can lie to myself about how time works. There, it’s never one season but all seasons if I look up. Just like Superman.

Today is the solstice. I won’t say which one. I like equinoxes better. You and I first met at an equinox. I won’t say which one. I had to cancel a trip to the Grand Canyon, which was fine with me because it’s too hot there like it is too hot where you live most of the time.

The Grand Canyon. You would think there would be no grass there, but grass grows everywhere. I like to imagine a condor flying over the great abyss. Black on red on orange, falling focus, strip of blue. Out of the feather of the condor a seed drops into the red and orange. What grass-forming nutrients would be possible there? But this is no Mars. This is Arizona. Grass clings to cliffs, fights its way into fissures, busts open cracks in a red sand wash.

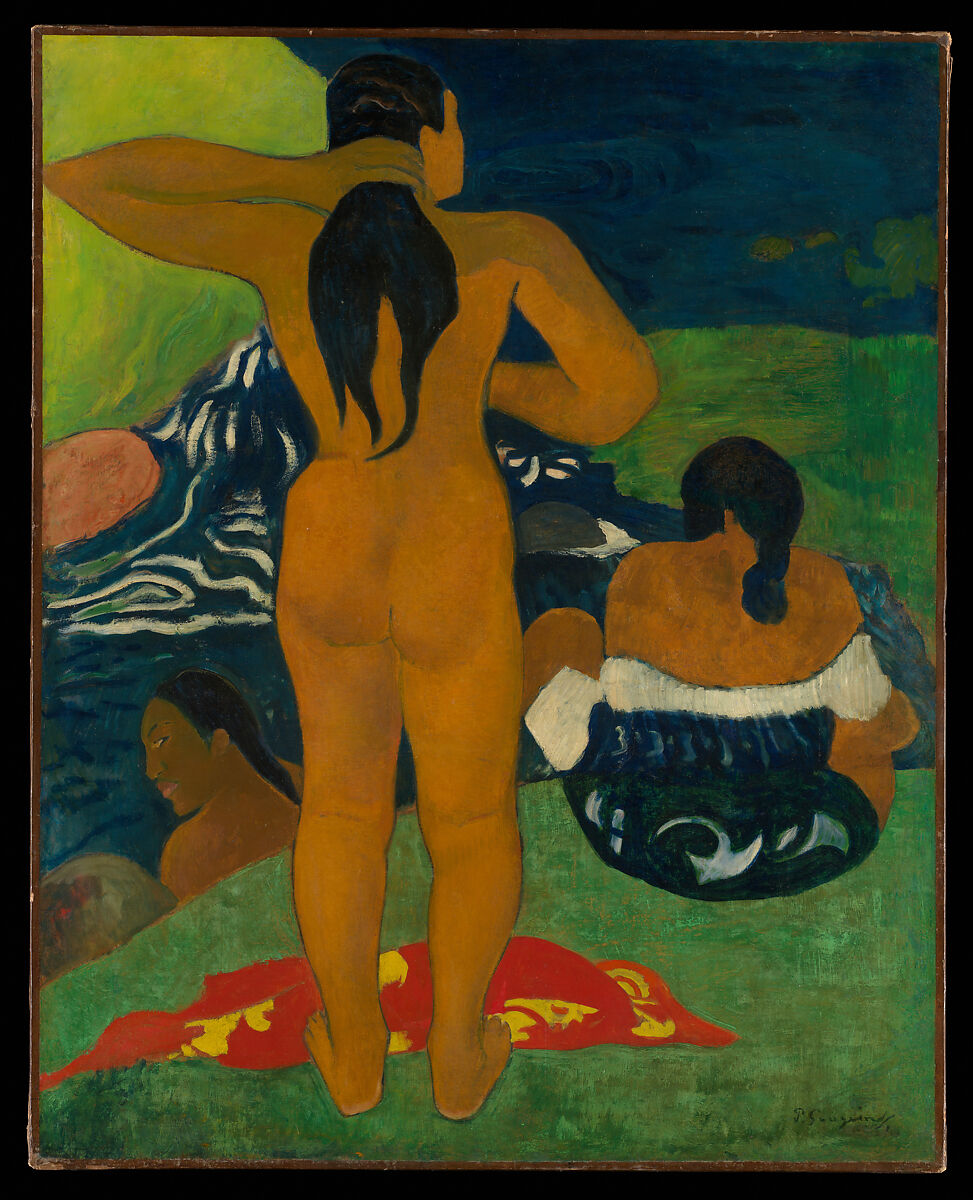

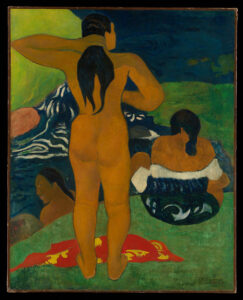

I would buy you a country made mostly of grass, like—in my imagination—your Australia. One as fat as a tropical equation where the solstice and the equinox are one. This country will bulge with abundance. Great big chickens and thick cigarettes, round Buddhas and platters of garlic. Cherries. Peaches. All served in bowls woven from the abundant grass that lines the marshes on the way to the sea—a warm sea. Where you can swim all year long without a wetsuit. Living in the U.S. is expensive. Three-bedroom, one-bath houses sell for a million dollars in Los Angeles, but that is no reason to lose hope. Los Angeles has lost its grass lines. Its sight lines. Its bylines. What we need, my friend, is a place with less traffic. More rain. People who don’t mind wearing hats while they type. In this country we will have a new kind of time. The kind of time that does not distinguish between deciduous and evergreen, between fall and spring, between marsh grass and cheatgrass, but instead tells us the difference between superheroes and real love until we realize none of these is so really opposite at all.

The Andrew Wyeth painting. You know the one with the woman sitting in the grass in the middle of a country—the grass is yellow, her hair is brown, curled into a bun? She wears a pink dress. She is on her knees. Or rather on her thighs. Maybe she’s crawling toward the house in the distance. Maybe she’s pining for the house in the distance. Maybe she has left the house behind and is saying goodbye. Do not Google “Christina’s World.” It will fold all those maybes in half. It will tell you something about some dread disease with the words Charcot Marie Tooth in its name. It will not help you understand the grass, the barn, the woman, or the season.

On the San Juan River, a tributary of the Colorado in Utah and Arizona, the river guide, Nate, who took Erik, me, and the kids down the river, docked the motor boat to make us lunch. After lunch, he pulled brown winter grass out of the ground. He twisted and folded and bent the thick grass into the shape of a deer. “Navajo are taught to make things out of grass,” he told us, and why shouldn’t we believe him? Grass has been here since the beginning on this not-Mars planet. It doesn’t take a superhero to know that permanence isn’t always green.