Elegy Written in a City Fish Market

Daniel Matthew Huppman

The best poet I know is a fishseller in the city. They are kind, direct, and full of feeling. They will take the skin from your salmon if you ask.

I was briefly a fishseller in the city—because I am cursed to answer yes to every question. I wore borrowed Grundens and a borrowed hat. I wore sneakers and my feet got cold and wet. Thankfully, the elder fishsellers were generous with their knowledge and patient with my inexperience.

When I was left alone, though, I became overwhelmed. The fish seekers were demanding. Remove the scales, remove the bones, remove the seeing eyes. They swarmed the counter. Be exacting in your cuts. This is for our family. My rising heat was trapped in the borrowed bib. Its color matched the orange of my energy. I disappointed countless fish seekers.

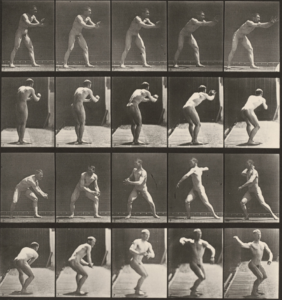

But the poet has become an excellent fishseller. They will not let the fish seekers down. Their fingers feel the buried bones as if guided by the divine. They pull them from the flesh with reverence. Their thin blade stays still as they free skin from body. When they brush away scales with the metal-toothed tool, they make what I thought was infinite disappear. There is fury in their motion. They create an iridescent rain, then a cleanness that lasts forever. It would be a mistake to see their skill as natural. No talent is simply given—not poetry; not fishselling.

I think of the poet often. My grave hope is that they have not been hardened by fishselling. That they aren’t stuck in it. I sometimes wonder what it would have been like if we’d become elder fishsellers together.

Could we have learned from each other and grown, or would we have become hard and turned against the fish seekers? Is hardness a virtue in fishselling? And how would we have treated the young poets when they arrived for their turn behind the counter? Could we find a balance in ourselves and impart it to the young ones?

Sometimes I worry that the seafood counter is like the country churchyard—the place where talent and goodness rest eternally. I want to reassure the poet that to rest and to die are different states. I want to beg them to not get stuck in it. Or if they do get stuck, I want to ask them to please not become hard. But then I remember the advice that I give to any young poet, or anyone unfortunate enough to hear to my advice: Do not take advice from me. Go on.