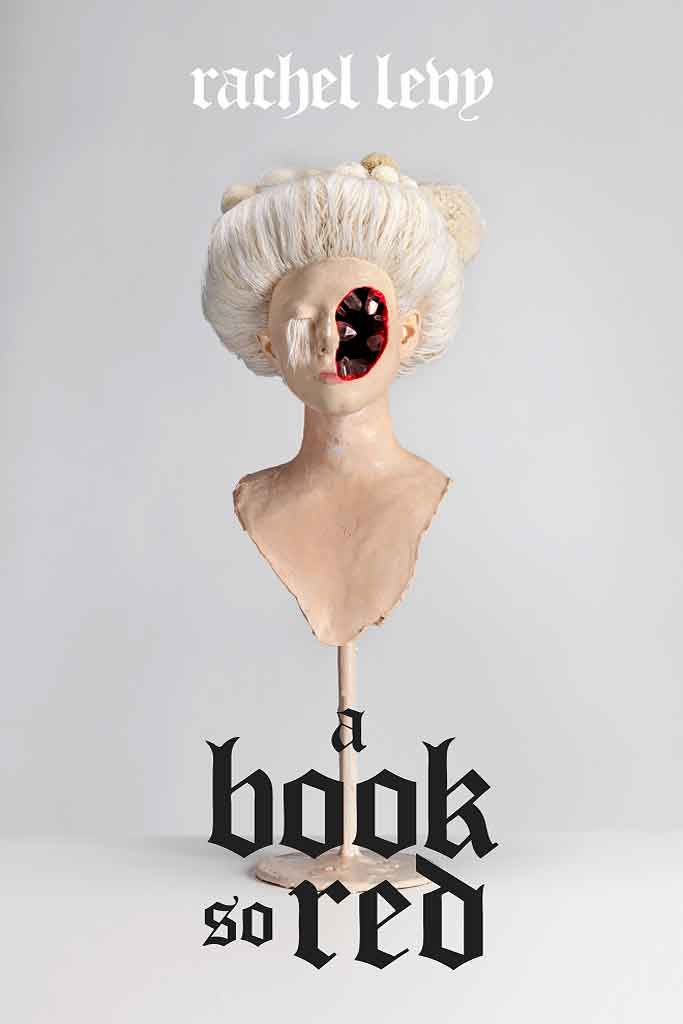

Review by Jaclyn Watterson // September 16, 2015

Caketrain Press, June 2015

Paperback. 140pp. $9

The lightning-quick flash fictions that make up Rachel Levy’s A Book So Red read like skin blistering: before you become aware of your delicious discomfort in such daring prose, there’s a bubble, erupting. Each section ends, leaving you a little sore, perhaps wishing for someone to hold your hand. Readers of Levy’s work are dazzled and humbled, made aware that life has more bite than we’ve acknowledged. This writer teaches us that, as one of her characters accuses another, we are bad tourists—we are reticent, and not nearly so capable of swallowing a stapled nipple, a beheaded horse, a dismembered, plastic foot, as Levy herself is in her lacerating sentences and knife-like forms.

It was impossible to be precise.

But one must choose a side. I must choose,

Levy writes. And she delivers; she chooses snippets of the most unsettling paroxysms, the most cutting images. She borrows from the conventions of fairy tales, 19th century marriage plots, and the spare realism of the late twentieth century—and ultimately overturns each of those forms, proving them insufficient for our time, capable only of partial truths. Levy’s own language is one that says partiality is truth; language is the only through-line. And she offers us language unfettered by fear or stupidity or the need to comfort or explain:

Some people move like they’re hugging the ground. They are bent at the waist, or they drag their bellies in the dirt.

What are they?

A. buckling beneath the weight of an outrageous labor

B. concealing a weapon.

This is the bed-time story your mother would have told were she as able to live within misery as Levy’s narrator, as unapologetic to admit: “I used to believe in the wholeness of things.” But the wholeness of things, be they narratives or characters or histories or relationships, Levy insists, is a myth we can no longer afford, a position none of us should be obsequious enough to take up. This is a bed-time story for the initiated and the unafraid among us, a bed-time story we can confront only when we are quite certain of our aloneness.

All the solace Levy has to offer is this: if we pay endless attention, if we give to our experience all the scrutiny it deserves, perhaps, in a lifetime, we too can generate a language to mediate it. Perhaps, we too can learn the resounding truth that:

Some wounds are best left untreated.

Some daggers should remain in the flesh, for removing them would serve only to drain the patient of blood.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER

Jaclyn Watterson’s fiction has been published in Birkensnake, The Collagist, Loose Change, Psychopomp, Yalobusha Review, and several other venues, and her reviews have previously appeared in Quarterly West. She is Assistant Professor of English & Creative Writing at Mercyhurst University in Erie, Pennsylvania.