Reviewed by Chloë Hanson | September 27, 2021

Lantern Press, 2021

Hardcover, 98 pages, $15.00

I first encountered Gretchen Primack’s work a few years ago, when a dear friend and colleague recommended the original publication of Kind to me in a poetry workshop. As a writer beginning to discuss nonhuman animals, their rights, and their lives in her own work, Kind was a revolutionary text for me — and I told Gretchen as much immediately upon finishing the book. Since then, I have recommended Kind to anyone who will listen, and I’ve taught several of the poems in my undergraduate courses. All this is to say, when given the chance to review the new, updated publication of Kind, I was ecstatic to revisit the book and see how the new additions enhanced what was already one of my favorite collections of poetry.

The updated Kind features ten new poems in addition to artwork by Dana Ellyn, Jane O’Hara, and Primack’s partner, Gus Mueller. Among these new additions are two Covid-related poems — a subject I, as a reader, am still wary of (it often seems to me that these poems slide into sentimentality). Primack’s “Covid I” and “Covid II,” however, fit into the collection while avoiding any of the pitfalls of the heavily-charged subject matter. Primack is acutely aware of the causal relationship between consuming nonhuman animals and viral epidemics (as explained in Reddy and Saier’s “The Causal Relationship Between Consuming Nonhuman Animals and Viral Epidemics” published in Karger in 2020), and she refuses to shy away from implicating humanity in the Covid pandemic — “Covid I” closes, “O human, see, you are important — . . . Just not/the way you wish.” “Covid II” extends this critique by focusing on the treatment of the oft-villainized pangolin who is transported, alongside pigs and chickens, to slaughter. In telling the story of the pangolin’s death in detail that is both grisly and beautiful (“when did hands pull/her smoothed balled body and slit/her throat for its tonic blood”), Primack begins to pick apart the common narrative that the nonhuman animals themselves are to blame for the spread of zoonotic disease. The similar deaths of the traditionally-farmed nonhuman animals in both this poem and the rest of the collection hammer Primack’s point home — there is no consumption of nonhuman animals that is without consequence.

Of the remaining eight new additions, standouts include “Apes, May I Speak to You a Moment?” and “When I Got There the Dead Opossum Looked Like.” Primack’s ability to make the reader feel a kinship to the caged and oppressed is remarkable; she is able to examine hard truths in a way that inspires the reader to do more for those they share the planet with without “preaching” to or alienating the reader. The aforementioned poems are particularly skillful in this regard. “Apes” allows the reader to examine how they, too, might be caught up in the same systems of oppression as nonhuman animals both as an oppressor and one of the oppressed:

“May I apologize? For the man holding us all

on strings . . .

. . . may I be sorry though I crumple

below my strings, never pull hard enough or make

the cuts? Though I dance for him as much as you?”

Similar to “Apes,” “When I Got There” draws the reader closer to their complicity in killing nonhuman animals. “When I Got There” is one of Primack’s most scathing poems in the collection, with lines like “there were sweets to buy/and his route crossed ours so we crossed/him out” and “His family wanted him, but there were ribs/to buy and manifest destiny.” Indeed, when someone eats a burger or a piece of fried chicken, it’s rare that they killed the chicken or cow themselves, or have even seen a slaughter take place. There’s plausible deniability — the person is removed from their role in the death of the nonhuman animal. Running over a possum or other creature, however, is a common experience, and one that many people find upsetting. Primack uses this shared experience to interrogate larger ethical questions regarding late-stage capitalism, industrialization, and, of course, eating meat.

Of the poems from Kind’s first publication, “The Dogs and I Walked Our Woods,” “Love This,” and “Mother II,” remain favorites. There’s a theme of motherhood and mothering running throughout Kind, but human mothering is not held above motherhood for any other species, which is evident in these poems. The speaker in “The Dogs,” for example, rejects the idea of giving birth and mothering a child because of the potential for bringing more violence into the world: “if I bore a child who suffered to see this, /or if I bore a child who gladdened to see this, or if/I bore a child who kept walking, I could not bear/it, so I will not bear one.” The ability to choose not to mother is contrasted with the lack of choice given to nonhuman animals. In “Love This,” the mother cow births a boy who is “dragged away by his back feet” while “her breast milk is banked for others” until “her gallons slow, we start over,/and her body says Love this! and she does.” “Mother II” addresses the perception of mothering outside of the human species even more directly: “Only humans mother . . . /Everything else spits out young.” Primack’s motherhood poems are among the most powerful in the collection, and have, in my experience, sparked lively discussion among students in the poetry and composition classrooms.

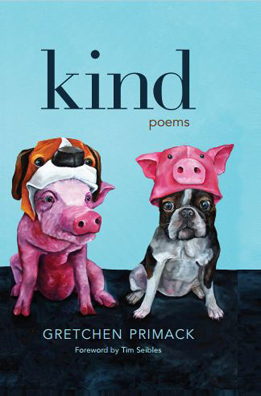

No review of this release of Kind would be complete without a mention of the artwork. The paintings included in this collection, in contrast to the violence so often described in the poetry, depict happy, living dogs, pigs, cows, elephants, and more. As such, Primack refuses to participate in glorifying or beautifying the needless deaths and exploitation of nonhuman animals; they are depicted only as Kind argues they should be — alive and thriving.

In all, though I was biased toward this release of Kind because of my previous experience with the book, I can say that the new poems and artwork add to, rather than detract from, the collection. Since Kind’s original publication, the cruelty of animal agriculture, zoos, circuses, and other exploitative industries have become more visible, resulting in a huge uptick of those following a plant-based lifestyle or identifying as vegan (from March 2019 to September 2020, for example, sales of plant-based meat products increased by 148 percent, while the USDA reports that licensed dairy operations in the U.S. have decreased by more than half since 2003). The exigence for this collection is clear, and the new poems addressing more recent current events, including the Covid-19 pandemic, only increase the authority of Kind in both poetic and activist landscapes.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gretchen Primack is the author of two other collections, Visiting Days (Willow Books Editors Select Series 2019), set in a maximum-security men’s prison, and Doris’ Red Spaces (Mayapple Press 2014), as well as an earlier version of Kind (Post Traumatic Press 2012). She also co-wrote, with Jenny Brown, The Lucky Ones: My Passionate Fight for Farm Animals (Penguin Avery 2013). Her poems have appeared in The Paris Review, Prairie Schooner, FIELD, Ploughshares, Poet Lore, The Massachusetts Review, The Antioch Review, and other journals and anthologies. Primack has administrated and taught with college programs and poetry workshops in prison for many years, and she moonlights at an indie bookstore in Woodstock, NY. Reach out to her at www.gretchenprimack.com.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER

Chloë Hanson received her PhD in Creative Writing (Poetry) from the University of Tennessee in 2020. Her current work focuses on the intersectional oppression of nonhuman animals and marginalized groups in Western, patriarchal societies. Her poetry has recently been featured or is forthcoming in Cimarron Review, Third Coast, The Rumpus, and Glass: A Journal of Poetry.