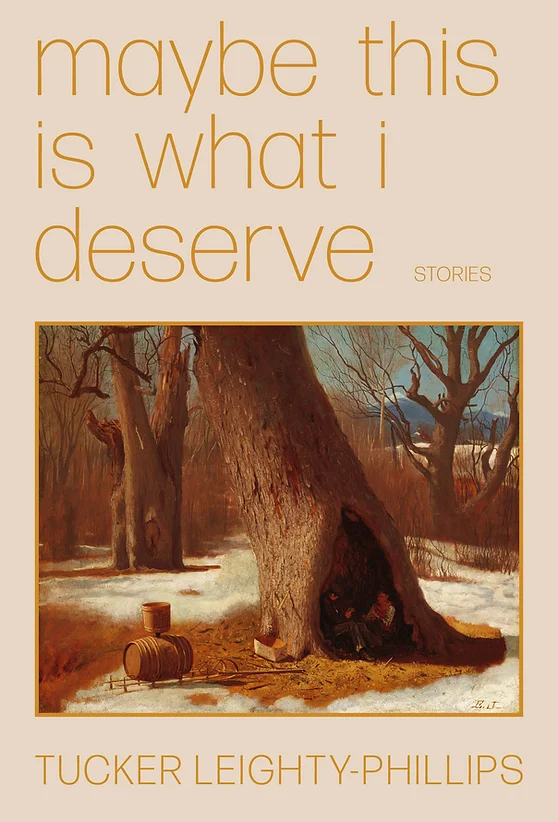

Reviewed by Shlagha Borah | July 21, 2023

Split/Lip Press, 2023

Paperback, $12

Tucker Leighty-Phillips’ flash fiction chapbook, Maybe This Is What I Deserve, is like blue cheese: it demands your undivided attention. It isn’t for quick, on-the-go consumption but a collection to be relished, slowly, with utmost care.

The collection starts with two epigraphs, one of which is by film director and producer, Wong Kar-Wai: “One’s memories aren’t what actually happened – they’re very subjective. You can always make it much better.” Kar-Wai, known for nonlinear storytelling and vivid, almost otherworldly cinematography, aptly deserves a place at the beginning of this collection. Leighty-Phillips cements the notion of the unreliability of memory and throughout the collection, justifies it. Even in the first story, “Down the tunnel, up the Slide,” we are let into the world of a child via the use of the second person. He writes, beginning the collection with a striking image – “This is how it begins: your father grants five minutes in the play-place while he orders two hamburgers.” The child/you play, explore, meet another child. The child/you find a “dum-dum sucker, an explosive shade of blue.” When the father comes back from buying hamburgers, the child/you wear your shoes and get out of the playpen, “The blue still purrs on your tongue.” Whether the narration of these stories makes the actual memory “much better”, slightly worse or simply unforgettable, I would leave you to gauge that.

One of the aspects that most astounded me is the deep attention Leighty-Phillips pays to worldbuilding, an extraordinary feat achieved in a collection strengthened by brevity. He is unafraid to lean fiercely into surrealist and fantastical elements – The Silver-Taloned Monster, the Catfish in the wishing well, the Royal Crown Cola Vending Machine as a boyfriend, the house that grew a head full of hair… The elements of the fictive present are so far beyond the world we live in, and yet, so strongly rooted in it. He invites the reader in, making a safe space, saying, “We’re a community, …, and I see you. I’m listening.”

The style and tone of these stories is further complicated because this collection plays around with the memory and experiences of children but are narrated by an adult voice. In “Toddy’s got lice again,” the story from which the collection pulls its title, Toddy “loves her lice like family” so much so that she goes looking for them, protects them, plays with them. Her mother, the first-person narrator, wonders if it’s her fault. Maybe it is because they’re poor. Or maybe “we find ways to turn our consequences into comforts, to say maybe this is good enough, maybe this is what I deserve.” I am floored at the way this juxtaposition of a child’s actions placed in contrast with a mother’s anxiety, written from a mirror of socio-economic crisis, is achieved in a story that does not even span a full page.

In line with his contemporaries like poet José Hernandez Diaz, whose work also heavily relies on surrealism and the prose form, Leighty-Phillips writes to make the reader uncomfortable, to have us question the truth as we know it. Whose memory do we trust, and why? These stories will make you laugh and make you weep, they will make you pause and think about unequal social structures but one thing they won’t give is the pleasure of satisfying endings.

In an interview with Evan Willians for Cleveland Review of Books, Leighty-Phillips talks about boundaries of genre and the in-betweenness of his work. When asked if his stories are flash fiction or prose poems, he says, “It’s interesting because it’s like, when you’re anticipating a poem or a story you kind of put different layers of expectations onto it, you know, like it’s going to do this to you or it’s going to move in this way.” As a writer experimenting with different genres, this interests me heavily because of the way writers train themselves on genre expectations to subvert them in their work. In this collection specifically, Leighty-Phillips reimagines and bridges the distance between flash fiction and prose poetry, with an undulating narrative voice and the unmistakable wit tying it all. The way these stories play with form, image and metaphor is admirable, delivering so much excellence at the sentence level, and beyond.

He not only does this in individual pieces but in the collection too, bending against the so-called rules of a flash fiction chapbook by including a five-page story, “The Rumpelstiltskin Understudies (Play)” right in the middle. In this avant-garde story structured like a Wikipedia article, Leighty-Phillips breaks all patterns established thus far – he characterizes himself in the third person, disrupts form and length, includes photographs and links – demanding enormous attention from the reader.

Leighty-Phillips uses peculiar Appalachian class markers in his work, and yet, I can relate them to a small town in India. With this community-centered collection, he has proved that specificity is, indeed, universal. A social commentary through and through, this collection doesn’t offer answers or solutions to the ugliness around us. But I attest, it will pull you back into its whirlpool with every reading, probing you to ask more and more questions.

ABOUT THE REVIEWER:

Shlagha Borah (she/her) is a multi-genre writer from Assam, India. Her work appears or is forthcoming in Salamander, Nashville Review, Identity Theory, Longleaf Review, Variant Literature, South Dakota Review, and elsewhere. She is a 2nd year poet in the MFA program at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and is an Associate Poetry Editor at Grist. Her work has received support from Brooklyn Poets and Sundress Academy for the Arts. She is the co-founder of Pink Freud, a student-led collective working towards making mental health accessible in India.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Tucker Leighty-Phillips (he/him) is a writer from Southeastern Kentucky. He is a graduate of the MFA in Fiction program at Arizona State University. His work has been published in Booth, Adroit Journal, The Offing, Wigleaf, and elsewhere. He has been anthologized in Best Microfiction and received a Notable Mention in Best American Sports Writing. Tucker writes about poverty, Appalachia, children, and family dynamics. His work has been supported by the Tin House Writers Workshop, Kenyon Review Writers Workshop, Art Farm Nebraska, Craigardan, and the Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing.