Review by Ryo Yamaguchi // August 15, 2016

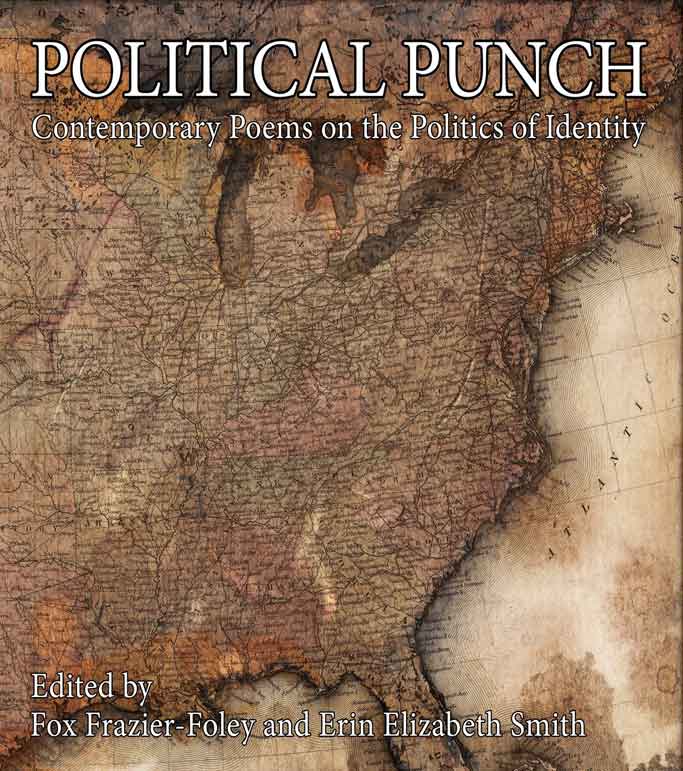

Edited by Fox Frazier-Foley and Erin Elizabeth Smith

Sundress Press, March 2016

Paperback, 236 pp, $20.00

When I finished reading Political Punch: Contemporary Poems on the Politics of Identity, edited by Fox Frazier-Foley and Erin Elizabeth Smith, I was waiting for my partner in Daley Plaza in Chicago under its famed Picasso sculpture. I could hear a din in the distance, and before I knew it, thousands upon thousands of Black Lives Matter protestors were roaring in the adjacent streets, banking south down Clark like an effulgent flood water caught in a hard ravine of steel and glass. The protestors were young and old; some carried enormous banners, some walked bikes, and many looked like they had just gotten off of work. They were white, black, Latino, Asian, South Asian, and Muslim, but they were unified in phrase: hands up, don’t shoot. All beneath Picasso’s elegantly deformed visage, that face that could belong to anyone.

What to make of the protestors’ powerful spondees and that modernist masterpiece (from a tradition often considered indifferent to politics) looming over one of the city’s central public spaces? Amy King, in her incisive introduction to the anthology, puts art—poetry—and politics like this:

Poetry carries and confirms the messy aspects of the body politic, implicating concepts beyond an observable reality by recognizing, interrogating, and at times even celebrating humanity’s spiritual and emotional heft. That is, just as a person is the existence of many conditions and states of being, so can poetry enact the political, convey the personal, and implicate the public simultaneously.

The project as it is set forth is most certainly characterized by such a balance of the personal, political, and public. And it certainly offers a diverse range of voices, though it is important to recognize the boundaries of that range: these are voices of the historically marginalized—including ethnic and racial minorities, the GLBTQ community, those with disabilities, and the disenfranchised working class—and, most often, these are American voices.

But within this range we encounter extraordinarily diverse accounts of the human experience and the striving against silence and systemic violence that have been central features of so many communities’ stories. There are several motivations that inform the rendering of these experiences. The most outright is simply the inscription of name, brilliantly executed in Chen Chen’s “Chen [No Middle Name] Chen],” which limits itself to the letters in its title:

called Chad called mini

called homo and ma’am

called no man called Chinaman

am I a man?”

But quickly we see such naming exercises as compressions of various forms of heritage, which open up resplendently in other poems. In “Lorca is Green,” Emma Trelles uses a vivid meditation on the iconic poet to arrive at a deeply savored remembrance of her mother:

Yellow is Pinar del Rio—heat and flat valleys and where my mother’s people are from. When I was a girl, yellow was the braid she wore long and down the middle of her back; yellow was the garden of succulents she grew, their branches circuitous and each leaf’s shape a surprise: a paddle, a button, a dagger, a heart.

That Trelles buries a dagger amid the beautiful items of her reminiscence is no accident. Violence is a critical element in the vast majority of these pieces, and it is often their explicit charge to engage it through witness and attestation. Raena Shirali is overwhelmed in “Stasis,” which begins:

From my tucked-knee coil I hear the news:

women are interviewed concerning kidnapping

& forgiveness, a girl hacks off her father’s head

with a kitchen knife after a weekend

in his room, a young woman is found

with her intestines ripped out—raped

with a crowbar—I cannot listen anymore.

It’s an intensely focused and yet coldly spoken newsreel, intimate traumas delivered in an abstract public form to an intimate listener—in tucked-knee coil—who cannot take it. From witness quickly follows the response—protest—such as CA Conrad puts forth, pulling no punches in “act like a polka dot on minnie mouse’s skirt:”

i am not a

family friendly

faggot i tell

your children

about war

about their tedious future careers

all the taxes bankrolling a

racist tyrannical military.

These brief examples highlight distinct features of the terrain of this anthology—name, heritage, witness, and protest—but many of the poems here navigate that terrain with more exploratory approaches, working through the thicket-like complexities of personal and public identity and the possibilities that arise from their intersection. The result, often, is exquisitely nuanced, sometimes buried in deep image, sometimes playful in tone, sometimes innovative in conceit. In her excerpt from “Post-Identity,” Carmen Gimenez Smith assumes an invisible bureaucratic position and interrogates us with this fusillade of questions:

what are three positive strains in you does discontent

drive you into the market does blunder drive you into the capital

when can you start with selective memorial is this firm what you had planned

was this a natal force are you an open boomtown or a crafted urn

or what animal rules the roost does that animal work as aphorism

pure revelation or dispatch you from the front lines of aesthetic warring

Have you made anything good with your outrage

Karen Skolfield, in “Arms Race,” fantasizes about punching an inconsiderate stranger—who has stretched her power cord across a busy aisle—in the face, and it quickly becomes an oddly humorous meditation on the escalation of violence:

When I walk over, she will look up, knowing she is about to be punched. In fact, she will welcome it. She will say that the very root of feminism is about everyone punching each other equally. In an air of solidarity, she will also curl her hand into a fist. We’ll stand this way for some time, openly admiring each other’s fist. . . . Eventually, one of us will raise her second fist into the air.

With a completely different approach, Oliver de la Paz haunts with high-saturation imagery in his superb address cycle, “Dear Empire (I)”:

These are your battlefields. There are monuments here, the dead atop stone horses with their eyes towards the heavens. Under shadow, the scrawl of graffiti and the hardscape of granite pathways guide foot traffic to the raised hoof of one of your dead generals mounted aloft.

What we see here and in so many other of these poems is not so much the direct events of suppression and expression but the haunting evidence of them, the trace—the statues and graffiti—that remind us that politics is, inevitably, a historical force, and that identity is always caught between the defining events of the past and the raw possibilities of the future.

There are far too many riches found in this anthology to be sufficiently captured in this brief review. No reader will like everything here, but this book, expertly compiled as it is, paints a detailed composite snapshot of both the cultural and poetic (from both emerging and established poets) diversities that should make us—despite the extraordinary hardships we endure—feel grateful. Perhaps Philip Metres, in his cycle “Homefront/Removes,” offers us something of an abiding epigraph for this collection, so let’s close with that: “Identity isn’t an end—it’s a portal, a deportation from the country of mirrors, an inflection within a question, punctuation in the sentence between birth and birth.”

ABOUT THE REVIEWER

Ryo Yamaguchi is the author of The Refusal of Suitors, published by Noemi Press. His poetry has appeared in journals such as Hayden’s Ferry Review, The Journal, and Gulf Coast, among others. He also regularly reviews books for outlets such as Michigan Quarterly Review and NewPages. He lives in Chicago where he works at the University of Chicago Press. You can visit him at plotsandoaths.com.